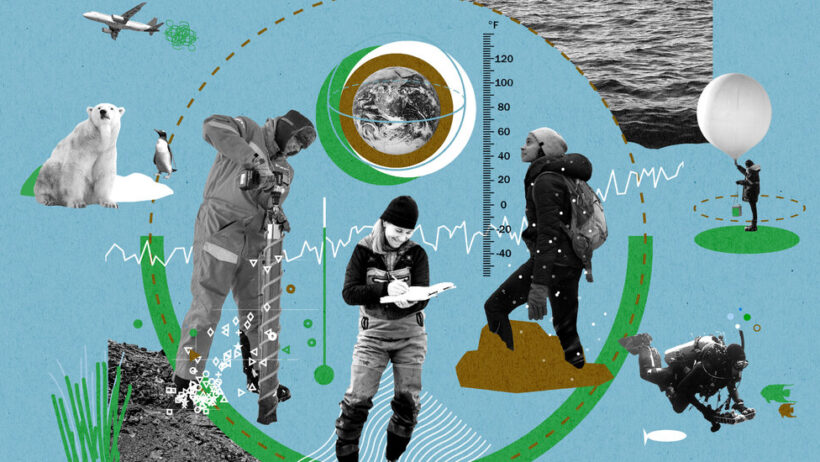

How did climate change affect early humans? This question invites us into the depths of our past, challenging us to explore the intersections of humanity and the environment. The Earth, throughout its geological history, has undergone significant climatic alterations, which have had profound implications for all living organisms, particularly early humans. As we delve into this fascinating discourse, we will uncover the strategies early people employed to survive amidst shifting seasons, the resources they relied upon, and the resilience they demonstrated in the face of inevitable change.

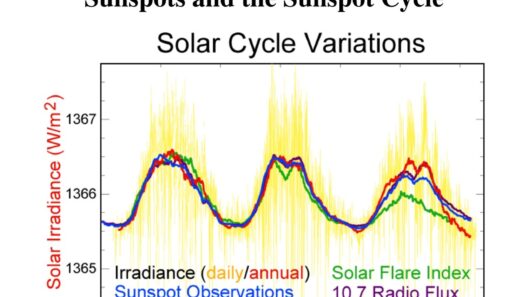

To understand the complex relationship between climate change and early human survival, we must first appreciate the variability of the Earth’s climate. Throughout the Pleistocene epoch, which spanned from approximately 2.6 million years ago to about 11,700 years ago, the planet experienced repeated glacial and interglacial periods. These cycles manifested as substantial alterations in temperature, precipitation, and vegetation, thereby reshaping habitats and ecosystems. Early humans were not passive observers; they were active participants, adapting in remarkable ways to the vicissitudes of their environment.

The late Pleistocene was characterized by dramatic climatic changes that stimulated the evolution of Homo sapiens. As glaciers advanced and retreated, they created a mosaic of ecotypes, presenting both challenges and opportunities for survival. For instance, during colder periods, expansive tundras replaced the lush savannahs of previous epochs. Early humans had to innovate their hunting and gathering techniques, as the availability of prey and edible plants fluctuated with the climate. Indeed, the development of sophisticated tools and communal hunting strategies can be directly linked to these environmental pressures.

Consider the scenario of early hunter-gatherers in a rapidly changing landscape. Imagine the gathering of a group, eyes squinting against the bright sun, their brow furrowed with concern. Some of their traditional hunting grounds are becoming barren, while others sprout new types of flora and fauna. A tapestry of dilemmas unfurls: how to secure enough sustenance? Which animals remain viable targets? Such questions drove early humans to migrate, forming bands that wandered in search of resources. This necessitated not only adaptability in diet—shifting from large terrestrial game to smaller animals and foraged plants—but also an evolving social structure. Survival depended on communication and cooperation, underscoring the social fabric woven through adversity.

As climatic conditions fluctuated, so too did the behaviors and diets of early humans. Evidence from archaeological sites suggests a remarkable resilience and opportunism. In periods of warmth, with the melting of glaciers, diverse ecosystems flourished. Rivers swelled with fish, trees bore fruit, and grasslands teemed with herbivores. This abundance allowed early communities to settle temporarily, leading to the establishment of semi-permanent encampments. Such shifts in settlement patterns provided key insights into the dietary transitions that occurred. The reliance on hunting dwindled slightly as plant-based foods gained importance, marking a fundamental change in the human diet that would eventually pave the way for agriculture.

Furthermore, climate change induced by glacial cycles also influenced the migration patterns of large game animals. Early humans, acting as keen observers of their environment, learned to track these animals, migrating alongside them as they searched for more temperate climes. This knowledge of animal behavior not only aided survival but also laid the groundwork for future hunting practices. As environmental conditions became increasingly unpredictable, the ability to predict animal migrations became a cornerstone of survival strategy. Flexibility in response to climate shifts was paramount, showcasing a stunning example of human ingenuity and adaptability.

However, these intermittent periods of plenty were often punctuated by sudden scarcity. The potential for famine loomed large, particularly during starker glacial maximums. It is within this context that the concept of risk management began to emerge in early human societies. Small groups developed strategies to mitigate the impacts of food shortages, such as storing food reserves or sharing resources among the community. The foresight to diversify food sources played a pivotal role in ensuring survival across varying habitats and seasons. This adaptability suggested an advanced understanding of their environment and, importantly, a shared culture around resource use.

Another critical element to consider is the impact of climate change on social cohesion. The pressures of survival likely fostered closer communal ties, resulting in increased cooperation, trading, and sharing of knowledge among groups. As early humans faced the challenge of changing seasons and resources, their survival depended not only on individual skill but also on the strength of their community. This collective resilience may have been a significant driver behind the socio-cultural evolution we observe in archaeological records.

Ultimately, early humans navigated a precarious existence for millennia, growing and evolving in tandem with the Earth’s climatic rhythms. The interplay between human ingenuity and environmental flux molded early societies in profound ways—a legacy that reverberates into contemporary discussions about climate change. Understanding how our ancestors coped with uncertainty might lend insight into the challenges we face today. As the Earth continues its transformation, may we draw inspiration from our early human relatives, embracing adaptability, cooperation, and resilience in an uncertain world.

In closing, as we reflect on the trials and tribulations faced by early humans, one must ponder: what lessons do these historical narratives hold for our own responses to climate change? As we forge ahead in an era defined by environmental challenges, could it be that the survival strategies of our ancestors provide guidance in navigating our own shifting seasons?