The climate of Northern Arizona is often typified by the iconic weather patterns observed at the Grand Canyon, but such a narrow lens overlooks the myriad complexities and regional variances that pepper this vast and diverse area. Could one argue that the climate of Northern Arizona is indeed a kaleidoscope, revealing different colors and patterns depending on where one looks? This inquiries us to delve deeper into understanding the climatic nuances that define not just the Grand Canyon, but the entire Northern Arizona landscape.

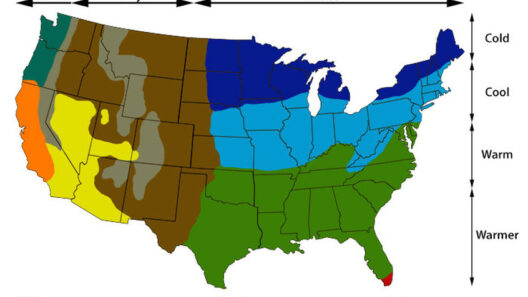

The climate in Northern Arizona is primarily categorized as a high desert climate, characterized by significant seasonal temperature variations, particularly between the day and night. The arid conditions of the region are punctuated by its elevation, which averages around 5,000 feet above sea level. This altitude transforms the area into a cooler oasis compared to other desert landscapes. Savvy travelers and residents alike can appreciate this as they prepare for excursions that range from sweltering days to brisk evenings, necessitating versatile clothing choices and plenty of hydration.

Aside from temperature, another significant factor that shapes the Northern Arizona climate is precipitation. Rainfall is scarce, averaging between 15 and 20 inches each year. However, it’s essential to note that this precipitation is not evenly distributed. The monsoon season, occurring from July to September, infuses the landscape with much-needed moisture. Storms during this period often arrive suddenly, dramatically altering the ambiance of the high desert with vibrant thunderstorms and cascading rains.

In stark contrast to the sunny disposition typically associated with the Grand Canyon, Northern Arizona features diverse microclimates. For example, the area surrounding Flagstaff, a city situated at a higher elevation, experiences more snowfall than its lower-elevation neighbors. Flagstaff’s snowy winters attract both tourists and locals, as they engage in winter sports and relish the transient beauty of snow-draped pines. This juxtaposition of climates across relatively short distances showcases the ecological variety that exists in Northern Arizona.

The flora and fauna of the region also reflect these climatic differences. The expansive pine forests of the San Francisco Peaks owe their existence to the cooler, wetter conditions at higher elevations, while the high desert shrublands, with their resilient sagebrush and cacti, thrive below. Such adaptability among plants is a testament to the resilience of life in Northern Arizona. One must wonder: How does this biodiversity impact local conservation efforts? Are we, as stewards of the environment, paying adequate attention to the delicate balance of these ecosystems?

Moreover, the relationship between climate and local culture is pronounced in Northern Arizona. The indigenous peoples of the region, such as the Navajo Nation and Hopi Tribe, have cultivated a deep connection with their environment, shaped by centuries of living in harmony with the land. Their traditional practices, agricultural techniques, and cultural stories often reflect a profound understanding of local climatic shifts and patterns. Nonetheless, in modern times, climate change poses unprecedented challenges to these age-old ways of life. Are we prepared to advocate for the rights and voices of these communities as they navigate an increasingly volatile climate?

As one gazes upon the breathtaking landscape of Northern Arizona, it becomes evident that climate change is remaking the script for the region. Rising temperatures threaten to exacerbate drought conditions, impacting water resources and elevating the risk of wildfires. These challenges usher forth a collective responsibility: Will we rally together to devise comprehensive strategies to mitigate these emerging threats? Local governments, organizations, and individuals must prioritize sustainable practices and conservation efforts to preserve the captivating beauty of Northern Arizona.

In addition to these pressing concerns, it is essential to consider the tourism industry, which plays a pivotal role in the region’s economy. While the Grand Canyon remains the star attraction, the fluctuating climate may deter visitors keen on enjoying a comfortable experience. A shift in tourist patterns could induce ethical considerations surrounding conservation versus commercialization. Should we endorse environmentally responsible tourism as a way to bolster local economies while protecting the vulnerable ecosystems that define this enchanting region?

Moreover, the climate of Northern Arizona offers substantial opportunities for research and education. Its diverse ecosystems serve as living laboratories for understanding broader climate issues. Schools, universities, and conservation organizations ought to seize this moment to foster educational initiatives that engage the community in climate literacy and environmental stewardship. How can we inspire the next generation to appreciate the intricate tapestry of climates that Northern Arizona possesses while empowering them to combat climate change?

In conclusion, the climate of Northern Arizona extends far beyond the perception of Grand Canyon weather. It encapsulates the interplay of altitude, precipitation patterns, and cultural narratives. This dynamic landscape presents an urgent call to action for environmentally-conscious individuals and communities to grapple with the ecological challenges on the horizon. We must act promptly, not only to preserve the natural beauty but also to safeguard the cultural heritage that has long thrived in harmony with the land. Northern Arizona is more than a destination; it’s a testament to resilience, adaptability, and the shared responsibility we embrace as stewards of the Earth.