The interplay between weather and climate is a fascinating yet often misunderstood aspect of environmental science. At first glance, these two terms might seem interchangeable, but they are fundamentally distinct concepts that underpin our understanding of the Earth’s atmospheric phenomena. Grasping the differences between weather and climate is not merely an academic exercise; it has profound implications for how we engage with environmental issues, policy-making, and our day-to-day lives.

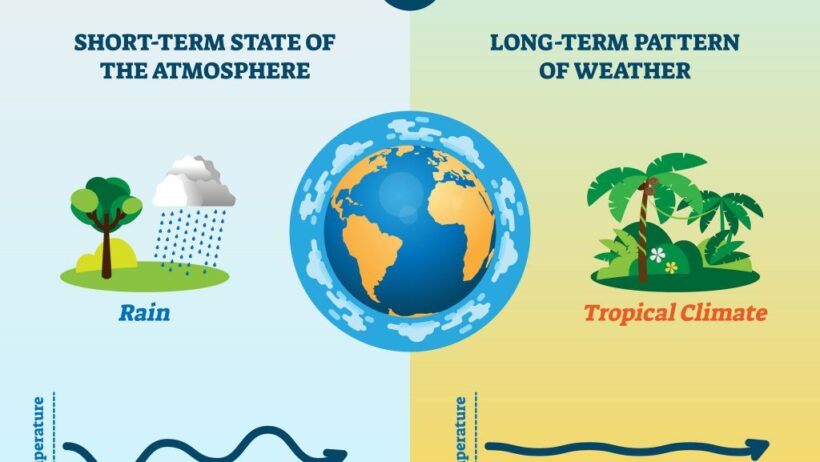

Weather refers to the short-term conditions of the atmosphere in a specific place at a specific time. It encompasses phenomena such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, wind, and visibility. A weather forecast might predict an incoming storm, a sweltering heatwave, or a cold front moving into an area. It is the immediate state of the atmosphere as we experience it over hours or days. These fleeting conditions can create a sense of urgency and immediacy, compelling individuals and communities to respond in real time.

Conversely, climate is the long-term average of these weather patterns over extended periods—typically 30 years or more—within a particular region. It integrates the variability of weather and paints a broader picture of what one might generally expect over the decades. For example, a region with a tropical climate will have warm temperatures year-round, abundant rainfall, and distinct wet and dry seasons. Understanding climate requires a broader temporal and spatial lens; it is an amalgamation of countless weather events contributing to a larger, more stable system.

The distinction between weather and climate is not simply semantic; it bears significant ramifications for how we interpret and respond to environmental changes. One of the core reasons for this difference is the scale and scope at which each operates. Weather can be unpredictable and erratic, while climate tends to follow patterns and trends. As such, what may appear as isolated weather events can emerge as indicators of broader climatic shifts. For instance, a single unusually hot summer does not automatically signify climate change; however, a protracted pattern of rising temperatures alongside other erratic weather phenomena can be indicative of a changing climate.

Recognizing this divergence becomes crucial in discussions about climate change. The conflation of weather and climate often leads to misunderstandings in public discourse. Individuals may experience a particularly frigid winter and loudly proclaim that climate change is a myth. Such an argument fails to consider that climate encompasses a much longer timeline and is reflective of averages and trends rather than singular events. The consequences of failing to appreciate this distinction are dire; they impede meaningful conversations and policy interventions that address the underlying causes of climate disruption.

Moreover, the implications of misunderstanding these terms are far-reaching. They permeate various sectors, including agriculture, urban development, and disaster preparedness. For instance, farmers rely on accurate weather forecasts for their day-to-day operations, while climate data helps them make long-term decisions regarding crop selection and resource management. An inability to properly distinguish between these two constructs might lead to adverse agricultural practices, economic strain, and food insecurity.

Urban planners, too, must consider both weather and climate in their strategies. Short-term weather events—like flash floods or heatwaves—demand immediate infrastructure responses, whereas long-term climatic trends dictate the design and durability of that infrastructure. Cities must evolve and adapt in response to shifting climatic norms; failing to account for these changes can lead to catastrophic consequences and increased vulnerability in urban populations.

In the realm of disaster preparedness, the distinction between weather and climate takes on life-or-death significance. Understanding regional climate patterns allows agencies to devise comprehensive emergency response plans, enhancing resilience to natural disasters. By focusing solely on immediate weather conditions, communities may underprepare for inevitable climatic challenges that arise periodically—events such as hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires are intrinsically tied to both weather phenomena and climatic trends.

As individuals, our understanding of weather and climate can reshape how we engage with environmental issues. Engaging with climate summits, supporting policies aimed at sustainable practices, and fostering conversations about climate change are all predicated on an informed populace. If citizens conflate weather with climate, they may underestimate the urgency of taking proactive measures to combat climate degradation. Public awareness and education are, therefore, vital. A well-informed citizenry possesses the power to advocate for meaningful change and hold policymakers accountable.

Understanding the nuanced yet critical distinction between weather and climate alters our perspective on environmental issues and prompts us to reassess our role as stewards of the Earth. We must recognize that while weather influences our daily existence, climate ultimately shapes the long-term health of our planet. Embracing this understanding allows for a more profound engagement with the pressing challenge of climate change, one that demands our attention and action in both personal and collective spheres.

In conclusion, the difference between weather and climate extends beyond mere terminology; it is a vital concept that informs our understanding of environmental dynamics and our responses to the unprecedented climate crisis. As we delve into this critical distinction, we must remain open to shifting perspectives, fostering curiosity and commitment to safeguarding our planet for future generations. Only through this lens can we appropriately evaluate, respond to, and mitigate the myriad challenges that lie ahead.