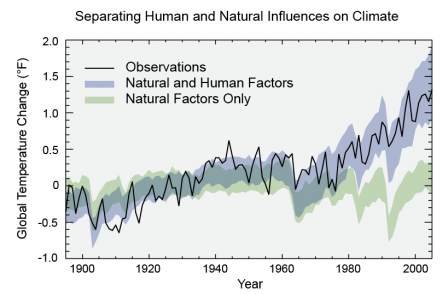

Climate change is an omnipresent specter, looming over discussions regarding the future of our planet and the wellbeing of its inhabitants. The phenomenon incites a blend of concern, urgency, and, paradoxically, fascination among the masses and experts alike. A common observation prevails: climate change is real and observable, yet its complexities make it difficult to assign explicit blame. As the overwrought debates continue, a pertinent inquiry diverges from the mainstream: How much of climate change is our fault? The exploration of the human factor in climate change unveils layers of responsibility that transcend mere carbon footprints and fossil fuel consumption.

At the crux of this inquiry lies an understanding of the anthropogenic contributions to climate disruption. The term “anthropogenic” denotes any change in natural systems that is attributed directly or indirectly to human actions. The duality of this term encapsulates the crux of the climate change dilemma, elucidating how our lives—steeped in industrialization, consumerism, and technological advancement—have precipitated drastic alterations in Earth’s climatic patterns. From the emissions of greenhouse gases to the deforestation of vast swathes of wilderness, it is integral to examine how deeply intertwined our actions are with the deleterious shifts in climate.

The science of climate change pivots fundamentally upon the Greenhouse Effect, a natural process that warms the Earth’s surface. In essence, sunlight enters the atmosphere, warming the planet, which then radiates energy back toward space. However, certain gases—carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O)—trap some of that outgoing energy, thereby retaining heat within the atmosphere. This insulative quality is exacerbated by human activities, notably through the burning of fossil fuels, deforestation, and agricultural practices. An alarming statistic illustrates this point: since the onset of the Industrial Revolution, CO2 concentrations have surged by more than 40%, largely due to human endeavors.

Delving deeper, one must explore the roles of various sectors contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. The energy sector stands as a formidable perpetrator, where reliance on coal, oil, and natural gas undergirds the global economy. The combustive processes necessary to harness energy in power plants, vehicles, and industries expel a significant quantity of greenhouse gases. Similarly, the agricultural sector, through livestock production and rice cultivation, releases copious amounts of methane, a greenhouse gas with a far greater heat-trapping capability than CO2 over short periods.

Inadequate land management practices, such as deforestation for agricultural expansion or urban development, exacerbate climatic woes. Trees serve as vital reservoirs for carbon; when logged or burned, they release stored carbon back into the atmosphere, further intensifying the greenhouse effect. The brutal irony is that our quest for progress—carving out land for habitation, industry, and food production—often leads to severe ecological ramifications, including loss of biodiversity, soil degradation, and the exacerbation of climate change itself.

Another subtle aspect of the human factor is the socio-political framework guiding our environmental policies. The systemic inertia toward fossil fuel dependency and unsustainable practices is often entrenched within political and economic paradigms. As governmental bodies grapple with the weighty task of enacting policies that prioritize the environment over immediate economic gain, the progression towards sustainability is delayed. This lethargy engenders a dichotomy between short-term benefits and long-term sustainability, where the immediate gratification derived from burning fossil fuels supersedes the somber understanding of future repercussions.

Public perception plays a pivotal role in understanding climate change responsibility. Trends in climate skepticism stem from a combination of misinformation, economic interests, and cultural attitudes. This nebulous relationship between science and societal beliefs can obscure the urgent reality of climate change, fostering an attitude of disengagement or fatalism. While it is tempting to resign responsibility to divergent players—governments, corporations, or even nature itself—it’s critical to recognize that individual choices accumulate into significant collective impact. Consumer behavior—from energy consumption patterns to waste production—perpetuates a cycle that contributes meaningfully to climate change.

Moreover, the narrative surrounding guilt and responsibility must traverse the terrain of fairness and equity. Developing nations—having historically contributed less to greenhouse gas emissions—often bear the brunt of climate change repercussions, such as extreme weather events and rising sea levels. As wealthier nations implemented industrial strategies that fueled global commerce, they often neglected the immediate environmental consequences, thus creating an ethical dilemma regarding reparative justice and responsibility. Addressing these disparities is paramount to formulating equitable climate action plans that respect both ecological integrity and human dignity.

However, rather than falling prey to despair or inaction, the human factor offers fertile ground for transformative change. The capacity for innovation and adaptation can emerge in response to the realization of culpability. Grassroots movements have surged, advocating for policy reforms, renewable energy initiatives, and sustainable practices. Individuals, communities, and organizations possess an unprecedented potential to eschew detrimental habits and champion environmental stewardship. Collectively, these efforts can trigger systemic shifts, embedding sustainability into the cultural fabric.

In essence, unraveling the question of how much climate change is our fault transcends mere individual actions; it encompasses our collective ethos, industries, policies, and societal structures. The culpability associated with climate change is intricate and multifaceted, requiring an embrace of responsibility and a reimagining of our relationship with the environment. As we navigate the path forward, embracing the agency that lies within our collective hands is imperative—propelling us toward a future where humanity’s impact is not one of destruction, but of rejuvenation and resilience in harmony with the planet.