Climate change is an ephemeral subject that dominates global discourse. The conflation of natural evolutionary processes and anthropogenic effects complicates our perception of climate dynamics. While Earth has witnessed fluctuations in climates over millennia, the current pace and magnitude of change evoke critical examination—one that beckons the question: is climate change primarily the result of human activity or a natural evolution of the planet itself?

Historically, Earth’s climate has altered due to a myriad of factors, including volcanic eruptions, variations in solar radiation, and continental drift. These phenomena have contributed to drastic transitions, such as the ice ages or the warmer interglacial periods. The innate resilience of Earth’s systems has allowed life to adapt through epochs. Nonetheless, the parameters dictating these shifts are different today. Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, human activities have introduced substantial alterations to the atmospheric composition, primarily through the combustion of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes.

The cornerstone of the debate lies in the examination of greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) are chief among those responsible for the greenhouse effect, wherein these gases trap solar radiation, leading to a rise in global temperatures. Historical data indicates that atmospheric CO2 concentrations have surged from about 280 parts per million (ppm) in pre-industrial times to over 410 ppm today. Such a rapid increase is starkly at odds with fluctuations seen in natural climate cycles.

By delving into paleoclimate records, scientists utilize ice cores, sediment layers, and tree rings to reconstruct historical climate conditions. These records unequivocally demonstrate that while Earth has experienced climate variability, the current rate of change is unprecedented when juxtaposed against geological time scales. This divergence necessitates scrutiny of the role human actions play in exacerbating or mitigating climate shifts.

Consider the effects of deforestation as a poignant illustrative example. The Amazon rainforest, often referred to as the “lungs of the planet,” not only serves as a crucial carbon sink but also regulates local and global climates. The destruction of vast areas for agricultural expansion and urban development releases stored carbon, thus intensifying the greenhouse effect. This practice disrupts not only atmospheric balance but also biodiversity, critically undermining the ecosystems that have evolved over millions of years.

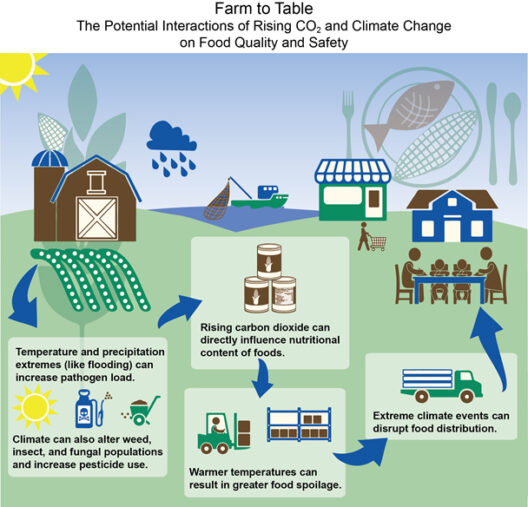

Transitioning from deforestation, we must examine transportation and energy sectors, the predominant contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. The reliance on fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—pervades global economies. Despite the advent of renewable energy technologies, stagnation in their deployment often results from infrastructural inertia and policy apathy. Fossil fuel combustion results in not only the emission of greenhouse gases but also particulate matter and pollutants that affect air quality and public health. Thus, the argument arises: while humanity indeed possesses agency over climate outcomes, it is dispassionate adherence to archaic energy paradigms that constrain progress toward sustainability.

Moreover, the impacts of climate change are no longer speculative; they manifest in observable phenomena such as rising sea levels, increased frequency of extreme weather events, and shifting biodiversity patterns. The merging of these realities with socio-economic dimensions reveals complex layers of vulnerability and adaptation. Communities on the frontlines of climate impact, often marginalized and under-resourced, bear the brunt of these changes despite contributing minimally to CO2 emissions. This intersectionality constitutes an ethical crisis that demands urgent rectification.

Nonetheless, the narrative that climate change is purely human-caused may oversimplify the intricate interrelations of natural systems. Events such as volcanic eruptions do lead to short-term climatic impacts, and natural climatic oscillations like El Niño and La Niña influence weather patterns. However, distinguishing between these short-term phenomena and the long-term trends driven by human activity is crucial. The imperative lies in recognizing that while natural processes are indeed foundational to Earth’s climate, the overwhelming evidence supports the assertion that the accelerating changes we presently face are significantly anthropogenic.

In addressing climate change, mitigation and adaptation strategies are paramount. Short-term solutions, such as transitioning to renewable energy sources—solar, wind, and hydroelectric—are essential, but structural shifts in policy and lifestyle are equally critical. This includes advocating for sustainable agricultural practices, enhancing waste management systems, and fostering planetary health through biodiversity conservation. Educational initiatives promoting awareness and ecological literacy can catalyze communal action, galvanizing societal momentum for comprehensive climate policy reforms.

International treaties such as the Paris Agreement illustrate the potential for collaborative efforts in combating climate change. These accords aim to unite nations in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, limiting global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. However, realization of these goals requires vigilance, accountability, and resilience from both governments and individuals alike. The interdependence of nations in the face of climate challenges underscores the necessity of collective responsibility—an acknowledgment that Earth is a shared habitat, and its preservation is a universal obligation.

In conclusion, the discourse surrounding climate change as either human-caused or a product of natural evolution is not a binary debate. It encompasses a spectrum of interactions, with anthropogenic influences emerging as the dominant factor in the current epoch of transformation. Recognizing the gravity of human impact necessitates a shift in perception—moving from a deterministic view of climate as a static entity to understanding it as a dynamic system responsive to human stewardship. As stewards of this planet, it is incumbent upon us to navigate this precarious balance with foresight and acumen.