The Paris Accord, often poetically referred to as a “global pact,” stands as a beacon amid the tumultuous seas of climate change negotiations. As nations grapple with the profound implications of a changing climate, understanding whether this accord constitutes a treaty requires diving into the nuances of international law, diplomacy, and environmental stewardship. This discourse will examine not only the technical definitions but also the implications and significance of this monumental agreement.

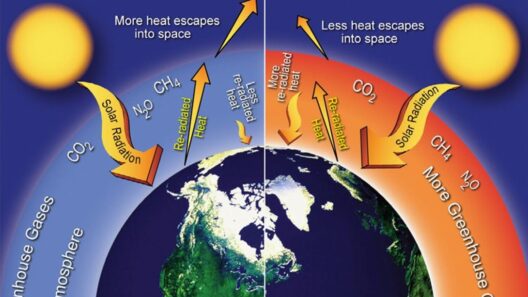

At its core, the Paris Accord emerged from the 2015 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) conference, also known as COP21, held in Paris, France. Here, the world seemed to coalesce around a singular yet complex ambition: to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, while also aiming for a more ambitious limit of 1.5 degrees. This universally binding commitment, however, raises the question of its categorization in the realm of international agreements.

Traditionally, treaties are formal agreements between sovereign states that require ratification to ensure compliance. They possess certain characteristics: they are legally binding, subject to international law, and instill obligations upon the signatories. However, the Paris Accord adopts a different approach, creating a framework that is distinct yet cohesive within the broader context of international climate governance.

Rather than dictating specific emissions reduction targets for each country, the accord adopts a more voluntary mechanism known as “Nationally Determined Contributions” (NDCs). Each signatory submits its own plans, detailing how it intends to contribute to the overarching goal of emission reduction. This method not only acknowledges the varying capabilities and circumstances of different nations but also fosters a spirit of equity, inclusion, and collaborative responsibility.

As one traverses the landscape of international climate agreements, it becomes evident that the Paris Accord adorns itself with a mosaic of flexible obligations. While it lacks the legally binding characteristics of traditional treaties, it encapsulates a spirit of commitment and accountability through its “ratchet mechanism,” wherein parties must periodically update their NDCs to reflect increases in ambition. This dynamic approach symbolizes a departure from the rigidities of past frameworks, illustrating a move toward a more adaptive and responsive climate regime.

Critically, the question of legal enforcement arises. Traditional treaties often possess mechanisms for compliance and enforcement, including sanctions for violations. The Paris Accord, on the other hand, relies on transparency and peer pressure among nations. Annual reporting and global stocktakes are fundamental components designed to facilitate accountability among countries, thus encouraging one another to enhance their commitments voluntarily rather than through coercive measures.

This intricate interplay leads to an essential understanding of the Paris Accord as an “adaptive treaty,” a term that acknowledges its innovative structure while adhering to the core principles of international climate cooperation. It navigates the complex waters of accountability without the burdensome weights of legal repercussions, thus cultivating a sense of global stewardship that transcends traditional diplomatic dynamics.

The unique allure of the Paris Accord is found in its emphasis on inclusivity and global participation. The participation of both developed and developing nations underlines the democratization of climate action, wherein all nations, regardless of their economic standing, are invited to partake in the pursuit of a sustainable future. This element aligns closely with the principles of climate justice, which acknowledges that the burdens of climate change disproportionately affect the most vulnerable populations.

Furthermore, the commitment to finance and technology transfer is pivotal within the accord, ensuring that developing nations, which often bear the brunt of climate impacts yet possess the least resources, can undertake significant climate actions. The provision of financial mechanisms acts as a lifeline, fostering resilience and the capability to implement sustainable practices worldwide.

Despite its transformative potential, the Paris Accord is not devoid of challenges. The voluntary nature of NDCs can lead to discrepancies in commitment levels, with some nations potentially underperforming or abandoning their pledges. This inconsistency necessitates vigilance from the global community to encourage and hold each other accountable, reinforcing the idea that combating climate change is a collective endeavor that no single nation can undertake in isolation.

Moreover, the unilateral withdrawal of any signatory, such as the U.S. instance of withdrawal and subsequent rejoining, exemplifies the precarious nature of international cooperation and the inherent vulnerabilities within an adaptive treaty framework. Each country’s determination to remain within this regime is essential to its integrity and effectiveness; thus, fostering goodwill and mutual understanding among nations remains paramount.

In conclusion, while the Paris Accord might not fit squarely into the traditional definition of a treaty, it serves as a remarkable testament to the evolving landscape of international climate governance. Its unique structure, centered on voluntary commitments, peer accountability, and inclusivity, establishes it as an unprecedented approach to tackling the global climate crisis. This multifaceted agreement not only binds countries to a common cause but also inspires collective action toward a sustainable future for all humanity, demonstrating that, indeed, the journey to combat climate change is as crucial as the destination itself.