China, a country sprawling across diverse terrains and latitudes, boasts a climate that is as multifaceted as its geography. The climatic conditions vary drastically from the frigid winters of the Mongolian plateau to the sultry summers influenced by monsoonal systems. So, what exactly shapes China’s climate? And how can we reconcile the challenges it presents? Let’s explore this intricate tapestry of weather patterns.

To begin with, it is crucial to understand the principal climatic zones in China. With such a vast expanse, the country experiences several distinct climatic regions: from the arid deserts of Xinjiang in the northwest to the humid subtropics of the southeast. Central to the characterization of China’s climate is the East Asian Monsoon, which has profound implications for precipitation patterns and temperature variations across the country. But why is it that some regions receive copious rainfall while others endure desiccation?

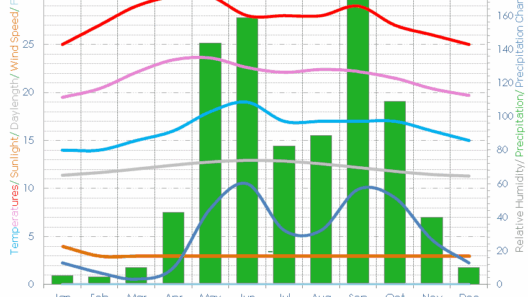

The monsoon, a seasonal wind that brings a dramatic shift in weather patterns, is typically divided into the summer and winter monsoons. The summer monsoon, originating from the southeastern seas, ushers moist air into southern and eastern China, stimulating torrential downpours and nurturing the lush biodiversity of the Yangtze River basin. Conversely, the winter monsoon, descending from the Siberian high-pressure system, blankets northern China with frigid, dry air, leading to stark temperature drops. The interplay between these monsoonal systems with local geographic features—mountain ranges, valleys, and plateaus—creates a mosaic of microclimates across the nation.

In the northeastern provinces, winters can be particularly severe, marked by subarctic temperatures that plummet below freezing. Cities like Harbin transform into winter wonderlands, famous for its Ice Festival. Yet, juxtaposed against these frigid conditions, the southern regions bask in a more temperate climate, experiencing milder winters and distinct wet and dry seasons. This climatic dichotomy raises an intriguing question: how does such variability influence the local ecosystems and the livelihoods of millions?

The diverse climatic zones also significantly impact agricultural practices. For instance, southern China’s warm, humid climate is ideal for rice cultivation, while the arid north relies heavily on drought-resistant crops and irrigation from river systems. However, as climate change intensifies, the sustainability of these practices is under threat. Will farmers in the northern regions be able to adapt to the increasingly erratic precipitation patterns? Or will they face crippling droughts that jeopardize their livelihoods?

Moreover, China’s varied climate also interacts with the vast topography of the Tibetan Plateau, often referred to as “the Roof of the World.” This elevated terrain influences weather patterns far beyond its borders, impacting monsoonal dynamics and contributing to global climate change challenges. The melting of glacial ice in the Himalayas, fueled by rising temperatures, threatens freshwater supplies for billions downstream. This raises a pressing dilemma: can China balance its development objectives with environmental sustainability in the face of such climatic crises?

The coastal regions, characterized by a maritime climate, experience high humidity with occasional typhoons and tropical storms, especially during the late summer and early autumn months. These violent storms can wreak havoc, causing flooding and destruction in coastal communities. The intersection of these storms with rising sea levels poses a severe challenge to urban centers like Shanghai and Guangzhou. Are these cities prepared for what climate change has in store for them?

While monsoons and winters sculpt China’s climate, another notable feature is the significant phenomenon of desertification in the northwest. The Gobi Desert and surrounding arid landscapes face severe ecological degradation due to human activities and climate change. As vegetation dwindles, the risk of sandstorms increases, leading to dire consequences not just locally, but also for regions downwind. In addressing this pressing challenge, innovative reforestation projects and sustainable land management practices have emerged. But the question looms: are these measures sufficient to reverse decades of environmental degradation?

As China grapples with its climate realities, the implications of climate variability extend well beyond borders. The interactions among different climatic regions can either engender coexistence or foster conflict over resources. For instance, the competition for water in drought-prone areas could ignite tensions among provinces if not managed effectively. How can cooperative strategies be implemented to ensure equitable access to water resources, fostering harmony in an increasingly fragmented landscape?

Thus, navigating China’s climate challenges requires more than adaptation and mitigation strategies. It calls for a comprehensive approach that encompasses an understanding of the historical context of environmental governance and the socio-economic dynamics at play. The question remains: can China lead the way in robust climate action while also uplifting its populace from the shadows of poverty? The answer lies not only in policy but in the collective will to forge a sustainable future amidst the climatic turmoil.

In summary, the climate of China is a compelling narrative interwoven with the threads of monsoons, winter chill, desert expanses, and maritime storms. The symbiotic relationship between climatic factors and human activity illustrates the urgent need for collaborative efforts to confront what lies ahead. The answer to the multifaceted tapestry of China’s climate can only be discovered through innovation, resilience, and an unwavering commitment to ecological stewardship as the nation charts its path forward in the face of climate uncertainty.