Chad, a country landlocked in north-central Africa, experiences a climate that is both diverse and extreme. The climate is largely influenced by its geographical positioning, which spans from the southerly Sahel region to the arid expanse of the Sahara Desert. This juxtaposition is a striking example of the heterogeneity in climates within a single nation, producing remarkable environmental consequences.

The northern part of Chad is dominated by the Sahara Desert, one of the harshest climates on the planet. This vast desert showcases an environment characterized by scorching temperatures, limited precipitation, and extensive sand dunes. Summers can be brutal, with daytime temperatures soaring above 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit). The prevailing conditions foster a desolation that challenges both human and ecological survival. The infrequent rainfalls, often measured as a mere 3 to 10 inches (75 to 250 mm) per year, create a stark contrast with the lush landscapes found in other parts of the world.

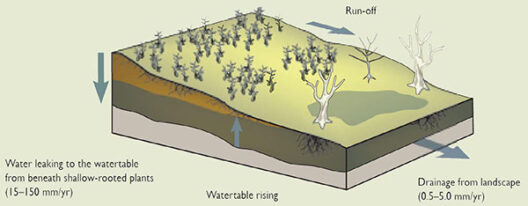

Expanding southward, one encounters the Sahel region, a transitional zone that marks the border between the arid Sahara and the more temperate savannas further south. The Sahel is characterized by a semi-arid climate, where rainfall becomes somewhat more predictable, averaging around 15 to 30 inches (400 to 800 mm) annually. However, this region is not immune to the climatic uncertainties that plague Chad. The Sahel has been afflicted by recurrent droughts, exacerbated by climatic fluctuations, which severely impact agriculture and food security. The relationship between rainfall and climate variability makes the Sahel a region of acute vulnerability.

During the rainy season, which typically occurs between June and September, the land flourishes for a fleeting window of time. This season is pivotal for subsistence farming, as it allows an array of crops to flourish. However, the rain can also be characterized by irregular patterns, manifested as erratic downpours followed by extended dry spells. Such variability breeds uncertainty, necessitating communities to adapt their agricultural strategies continually. Resilience becomes a vital trait as farmers navigate the challenges posed by climate extremes.

The unique climatic factors in Chad have led to diverse ecological settings. While the northern expanses are stark and often surreal, the southern regions feature moist savannas, where acacia and baobab trees flourish. These ecosystems rely heavily on the seasonal rains, which infuse life into the barren soil. Wildlife thrives under these conditions, with creatures well-adapted to endure both extreme heat and arid conditions. However, climate change poses an ominous threat to these delicate balances. The interplay between the Sahara and Sahel has far-reaching implications not only for biodiversity but also for human livelihoods.

Climate change evokes quite a multifaceted conundrum for Chad. While the nation has historically contributed minimally to global greenhouse gas emissions, it stands squarely in the crosshairs of climate-related adversities. These include increasing desertification, more pronounced droughts, and erratic rainfall that jeopardizes agricultural productivity. The compounded effects of climate shifts pose imminent dangers to countless Chadians who depend on farming and pastoralism.

Moreover, the shrinking Lake Chad, once one of the largest freshwater bodies in Africa, epitomizes the climatic transition occurring in the region. Over the years, it has diminished by approximately 90%, primarily due to climate change and unsustainable usage, leading to dire consequences for the surrounding communities reliant on its waters for fishing and irrigation. The lake’s decline underscores a haunting narrative of resource scarcity and geopolitical strife, drawing into question the intersection of environmental and social justice.

Contemplating the resilience strategies adopted by communities in Chad offers a perspective of hope. Although the challenges are considerable, individuals and organizations are increasingly foregrounding innovative practices to cope with a climate in flux. For instance, adopting climate-smart agriculture can bolster agricultural productivity while minimizing ecological footprints. Agroforestry, which intertwines the cultivation of trees and crops, presents an alternative method to sustain soil health and enhance biodiversity.

Another significant initiative encompasses community-based water management systems. By harnessing traditional knowledge intertwined with modern techniques, communities are developing strategies to optimize limited water resources. These initiatives not only advance water conservation but also empower local populations to take proactive roles in mitigating climate-related threats.

Nonetheless, the commitment to addressing climate issues in Chad must extend beyond localized adaptations. International collaborations and support will be imperative in bolstering community initiatives and enhancing resilience. Awareness-building and education regarding the interconnectedness of global climate systems are crucial elements. Engaging stakeholders at various levels can galvanize resources and facilitate viable solutions that transcend borders.

In conclusion, the climatic dichotomy in Chad serves as a testament to the intricate relationship between natural environments and human societies. The Sahara’s relentless sands and the Sahel’s heat synthesis a narrative imbued with challenges and opportunities. As we grapple with the realities of climate change, it becomes increasingly clear that understanding diverse climatic conditions is essential in crafting holistic, equitable responses. Engendering curiosity about Chad’s climate not only highlights the nation’s unique context but also propels a collective responsibility towards fostering sustainability in the face of an ever-evolving global climate landscape.