Iceland is often celebrated as the land of fire and ice, a juxtaposition that aptly describes its striking geological features and climatic complexities. Situated just below the Arctic Circle, Iceland’s climate is considerably influenced by both oceanic and atmospheric conditions. This article delves into the nuances of Iceland’s climate, exploring its diverse weather patterns, unique geological formations, and the environmental challenges, particularly in the context of climate change.

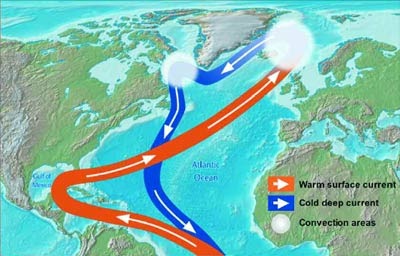

To comprehend Iceland’s climate, one must first consider its geographical positioning. The island nation is located in the North Atlantic, which means it is subjected to the prevailing westerlies and the North Atlantic Current. These oceanic influences moderate its temperatures compared to other regions situated at similar latitudes. Summers can be surprisingly mild, while winters, although cold, are often less severe than one might anticipate.

Iceland experiences a subarctic climate, characterized by cool summers and cold winters. The coastal regions enjoy milder temperatures due to the warming effect of the North Atlantic Current. In contrast, the interior highlands exhibit more extreme conditions, with harsher winters and cooler summers. The average temperature in Reykjavik, for instance, ranges from about 1°C (34°F) in January to 11°C (52°F) in July. However, these averages can swing dramatically due to various atmospheric phenomena.

Weather in Iceland is notoriously capricious. A typical day can produce a melange of sunshine, rain, snow, and strong winds. The term “If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes” is frequently heard among locals. This unpredictable nature stems from Iceland’s unique topography, which includes glaciers, volcanoes, and geothermal fields. The diversity in landscape contributes to regional microclimates that can change rapidly, especially in areas influenced by elevation or proximity to the coast.

Moreover, the climate is notably influenced by volcanic activity. Eruptions can lead to significant changes in weather patterns. For instance, the 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption not only disrupted air travel across Europe but also altered local climatic conditions. Ash clouds and changes in atmospheric composition can lead to cooler summer temperatures and affect precipitation levels. As a result, Icelanders have become accustomed to adjusting their lives around both natural and manmade climatic alterations.

Precipitation in Iceland varies greatly across different regions. Coastal areas typically receive more rainfall, while the northern regions are drier. On average, Iceland receives about 1,200 millimeters (47 inches) of precipitation annually, most of which falls during the autumn and winter months. Rainfall tends to be less concentrated in the summer, although occasional downpours do occur. Snow is common during the winter, contributing to the island’s stunning landscapes and feeding the glaciers that define its topography.

One of Iceland’s most prominent features is its glaciers, which play a crucial role in the country’s hydrology and climate. Glacial ice acts as a buffer against changes in temperature, reflecting sunlight and contributing to cooling in surrounding areas. However, climate change has led to accelerated glacial melt, with reports indicating that Iceland’s glaciers could disappear by the year 2100 if current warming trends continue. This phenomenon not only affects local ecosystems but also has broader implications for global sea levels.

The interplay between ice and fire is particularly evident in Iceland’s geothermal landscape. With its volcanic activity, the island harnesses geothermal energy as a sustainable resource, supplying about 90% of its domestic heating and a significant portion of its electricity. This has positioned Iceland as a leader in renewable energy, showcasing a model of sustainability amidst challenges posed by climate change. The use of geothermal energy also mitigates greenhouse gas emissions, thus playing a role in the global fight against climate change.

Furthermore, the effects of climate change are manifesting in various forms, ranging from altered species habitats to changing migratory patterns of birds and marine life. Warmer temperatures are leading to shifts in vegetation zones, which can disrupt traditional practices such as fishing and agriculture. As the Arctic warms, new opportunities present themselves, such as increased shipping lanes, but they also bring significant risks, including biodiversity loss and the potential for oil exploration in fragile ecosystems.

In conclusion, Iceland’s climate is a fascinating study of contrasts, heavily influenced by its geographical location and geological features. The island serves as a microcosm of the larger climate crisis, illustrating both the beauty of the natural world and the vulnerabilities facing it. With glaciers melting and volcanic activity shaping the landscape, the interplay of fire and ice will continue to be a defining characteristic of this unique environment. As the world grapples with the realities of climate change, Iceland stands at the forefront, offering vital lessons in resilience, sustainable energy, and the urgent need for environmental stewardship.