Climate change is often described as a slow-moving, yet monumental, freight train barreling down the tracks of human existence. As the wheels clatter loudly against the rails, the question arises: what percentage of climate change can be attributed to human activity? Understanding the nuanced factors contributing to climate change is paramount in grasping the enormity of the problem and figuring out how to mitigate its effects.

Historically, the Earth has undergone numerous climatic fluctuations. Ice ages and warmer interglacial periods have shaped ecosystems and influenced the very fabric of life. However, the current epoch—often referred to as the Anthropocene—marks a distinct pivot point. Human beings have transitioned from passive observers of climate variability to active architects of environmental change. It is estimated that approximately 70 to 90 percent of the current climate change phenomenon is driven by anthropogenic factors. This statistic paints a daunting picture, revealing the extent to which our activities are interwoven with the planet’s climatic destiny.

The heart of this human-induced climate alteration lies in the emission of greenhouse gases (GHGs). These gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O), are primarily the result of industrial processes, agriculture, deforestation, and fossil fuel combustion. Consider the atmosphere as a thick blanket; as the emissions accumulate, the blanket becomes increasingly snug, trapping heat and driving global temperatures upward. With every ounce of CO2 released from a vehicle’s tailpipe or a coal-fired power plant, we exacerbate the greenhouse effect.

Yet, unraveling the intricacies of GHG emissions reveals a complex tapestry. For instance, while CO2 is often heralded as the chief culprit due to its abundance, methane—a gas emitted during agricultural practices, particularly from livestock—wields a far more potent effect on atmospheric warming. Over a 20-year period, methane has a global warming potential that is 84 times greater than CO2. This difference underscores the necessity for nuanced strategies aimed at reducing emissions across various sectors.

Moreover, land use changes significantly contribute to climate change. The removal of forests to create agricultural land not only releases stored carbon but also diminishes the planet’s capacity to absorb CO2. Forests act as the lungs of the Earth, and with diminishing woodland cover, this crucial mechanism of carbon sequestration falters. As human encroachment into natural habitats intensifies, the repercussions are twofold: we release carbon into the atmosphere while simultaneously dismantling the systems capable of offsetting those emissions.

It is essential to delve deeper into the data surrounding climate modeling. Scientific projections indicate that if current trends in GHG emissions continue unchecked, we could witness a rise in global temperatures by an alarming 3 to 4 degrees Celsius by the end of the century. Such changes would be akin to upending society from a lush, temperate landscape into a parched, hostile environment. Resulting effects would resonate through violent weather patterns, sea-level rise, and unprecedented species extinction rates.

Moreover, feedback loops—with their spiraling, often cascading effects—complicate the existing trajectory of climate change. For example, ice melts reveal dark ocean water beneath, which absorbs more sunlight than reflective ice. This further exacerbates warming, leading more ice to melt in a perilous cycle. In this context, our understanding of the climate crisis becomes critical; every increment in temperature catalyzes unforeseen environmental repercussions, perpetuating a cycle that is difficult to reverse.

Engaging in discourse about the percentage of climate change caused by humans is more than a mere academic exercise. It also demands addressing the myriad social, political, and economic ramifications. The dichotomy between developed and developing nations is stark; industrialized countries have historically contributed the most to greenhouse gas emissions, while developing nations, despite negligible contributions, are often the first to suffer the consequences of climate change. This reality invokes a moral imperative for wealthier nations to lead the charge in mitigating this global crisis.

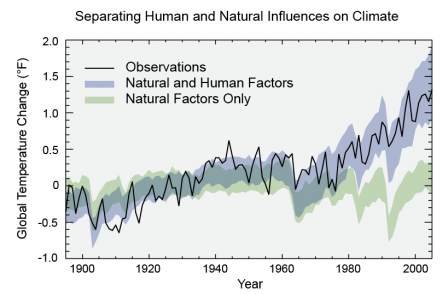

Activism plays a crucial role, galvanizing communities and fostering awareness. The narrative of climate change as an entirely human-centric phenomenon, however, is sometimes met with resistance. Some argue that natural variability in the Earth’s climate should not be overlooked. While it’s undeniable that the Earth has undergone alterations due to natural phenomena—such as volcanic eruptions or solar fluctuations—the irrefutable evidence from contemporary science highlights that, currently, human activities are the primary drivers of change.

In conclusion, while various natural factors have historically influenced the Earth’s climate, the significant proportion of recent climatic shifts—an estimated 70 to 90 percent—can be traced back to human actions. The ongoing challenge lies in shifting the collective mindset toward sustainable practices. Transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, reforesting areas, and rethinking agricultural strategies are not merely aspirational goals—they are desperate necessities. Recognizing the profound impact of human behavior on our planet’s future is the first step toward a more sustainable and resilient world. As the climate continues to evolve, the onus is upon humanity to steer the course toward a more hopeful trajectory, emphasizing the capacity for change through informed action.