Food digestion is a fascinating process that exemplifies the conservation of mass and energy, essential principles governing biological and physical transformations. This intricate sequence transforms organic matter into usable energy while adhering to the laws of thermodynamics. Understanding how mass and energy are conserved during digestion offers insight into how we fuel life efficiently, which bears significant implications for environmental sustainability, especially in the face of climate change.

The digestive process begins with the ingestion of food, where it is mechanically and chemically broken down into its constituent molecules. This initial stage is crucial as it sets the stage for deeper enzymatic action. The breakdown of food involves a plethora of enzymes that facilitate the disassembly of complex macromolecules such as carbohydrates, proteins, and fats. This disassembly is governed by the principle of conservation of mass, where the total mass of the reactants (food) is equal to the total mass of the products (nutrients and by-products), affirming that mass cannot be created or destroyed.

As food is consumed, it is subjected to a series of transformations, starting in the mouth and continuing through the gastrointestinal tract. In the mouth, enzymes in saliva begin the breakdown of carbohydrates, primarily starches, converting them into simpler sugars. This initial step is where the mechanical action of chewing amalgamates with the chemical action of saliva, leading to the formation of a bolus that is swallowed and transported to the stomach.

In the stomach, the environment becomes more acidic, primarily due to the presence of gastric acid (hydrochloric acid). This high acidity serves multiple functions, including denaturing proteins, thereby making them more accessible to enzymatic breakdown. The enzyme pepsin becomes active in this acidic medium, specifically targeting protein molecules and cleaving them into smaller peptides. Here, we observe another profound application of the law of conservation of mass; even though the food appears transformed, its original mass remains intact, merely redistributed as different molecular species.

Continuing into the small intestine, the food mixture encounters bile salts and pancreatic juices, which facilitate further breakdown. Bile emulsifies fats, increasing their surface area and allowing enzymes like lipase to act more effectively. The carbohydrates continue to be hydrolyzed into monosaccharides, proteins are further degraded into amino acids, and lipids broken down into fatty acids and glycerol. This complex biochemical symphony orchestrates the efficient extraction of nutrients, maximizing the energy potential stored in each macromolecule.

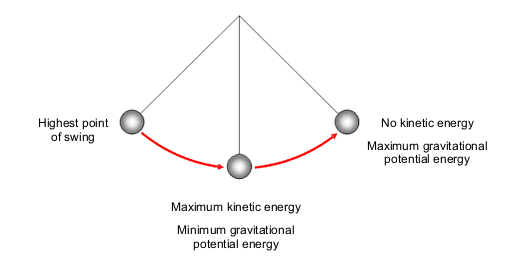

Energy conservation during digestion operates under the principle that energy, like mass, cannot simply vanish. Instead, it is transformed. The calories derived from macronutrients are ultimately converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the cellular currency of energy. This transformation is governed by metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, the Krebs cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation, which encapsulate the conversion of food energy into usable forms for cellular activities. Each step in these pathways exemplifies the principle of energy conservation, where energy transformations ensure that the energy harvested from food is not lost but rather stored or utilized within the biological system.

Furthermore, the process of cellular respiration, which utilizes the end products of digestion, showcases how efficiently energy is harnessed. During cellular respiration, glucose and other biomolecules are oxidized, releasing energy that is harnessed to manufacture ATP. This energy transfer is dynamic, reflecting a continuous cycle that underscores the interconnectedness of the digestive process and cellular energy dynamics. Carbon dioxide and water are the by-products of this metabolic process, illustrating not only the conservation of mass but also the resultant matter that, while considered waste, contributes back to the environment, emphasizing a cycle of life.

As the nutrients are absorbed through the intestinal walls into the bloodstream, they are transported throughout the body, fueling growth, maintenance, and repair at cellular levels. The efficiency of digestion and energy transfer underscores the significance of this biological system in not only sustaining life but also in minimizing energy waste. However, the questions we face today extend beyond mere digestion; they touch on sustainability and environmental repercussions.

Food waste represents a profound challenge, with massive amounts of perfectly edible resources ending up in landfills, contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. By focusing on maximizing the efficiency of the digestion process and reducing waste, we can significantly impact our carbon footprint. Strategies to enhance digestion efficiency, such as promoting plant-based diets or utilizing innovative food preservation technologies, align with environmental activism to combat climate change. Food sustainability defines a pathway toward reducing mass waste while simultaneously ensuring energy conservation through better consumption practices.

In conclusion, the digestion of food elegantly illustrates the dual principles of mass and energy conservation. As food undergoes transformation through enzymatic and metabolic processes, we see how natural systems operate in accordance with fundamental physical principles. The ability to harness energy efficiently while conserving mass not only sustains life but also offers a blueprint for addressing broader environmental concerns. By integrating this understanding into our daily lives and promoting sustainable practices, we can appropriately respond to the urgency of climate change while ensuring that we respect the delicate balance of our natural ecosystems.