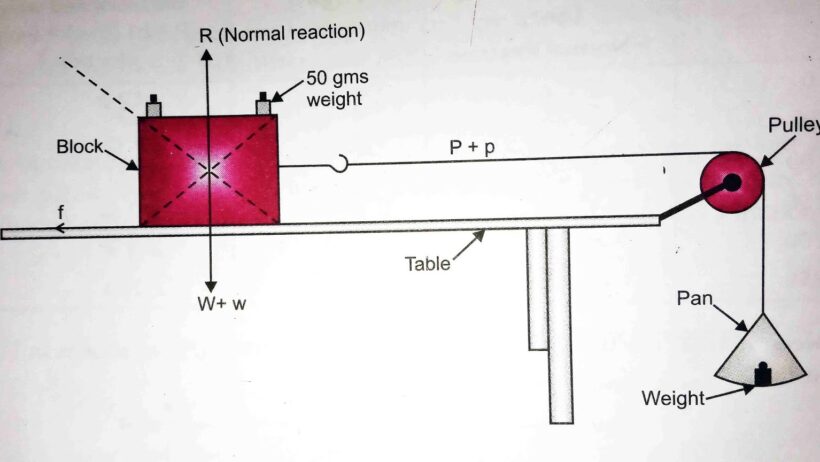

Understanding the mechanics of friction can significantly enhance one’s comprehension of classical physics. The concept of friction often seems straightforward, yet a more nuanced examination reveals its complexities. This exploration will delve into how we can utilize the principle of conservation of energy to measure frictional forces in various contexts. By the end of this discussion, a shift in perspective regarding friction will be apparent, as well as the potential for innovative experimentation.

At its core, friction is a resistive force that opposes the motion of one surface relative to another. We encounter this force in everyday life—when walking, driving, or even writing. The significance of friction cannot be overstated; it is the very force that allows us to grip surfaces and facilitates vital everyday activities. However, quantifying friction often eludes students and seasoned physicists alike. Traditional approaches frequently involve cumbersome measurements of static and kinetic coefficients, which can lead to a loss of interest in the underlying principles. Here, we propose an engaging method using the conservation of energy to illuminate this often-misunderstood phenomenon.

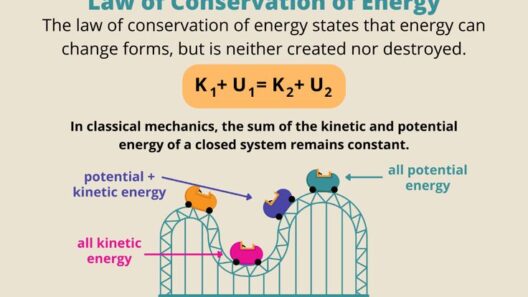

The conservation of energy principle states that the total energy within an isolated system remains constant over time. In practical terms, energy can transform from one form to another, but its total must remain conserved. This concept can be applied to scenarios where friction plays a crucial role, particularly in experiments that involve inclined planes or sliding objects. These setups create environments where gravitational potential energy converts into kinetic energy, thereby providing a fertile ground for investigating frictional forces.

To begin, consider an inclined plane—an object sliding down an angled surface offers an ideal opportunity to observe energy transformations. As the object, say a block of wood, descends the incline, it converts gravitational potential energy into kinetic energy. If no friction exists, the energy calculations would be straightforward. However, the presence of friction complicates these calculations and provides a unique means to quantify its effects.

To frame the experiment, we first establish the inclined plane’s height and angle. The gravitational potential energy (PE) at the top can be expressed as:

PE = mgh

where ‘m’ denotes mass, ‘g’ represents the acceleration due to gravity, and ‘h’ is the height of the incline. As the block descends, its potential energy diminishes while its kinetic energy (KE) increases, expressed as:

KE = 0.5mv^2

As the experiment progresses, it is vital to acknowledge that not all potential energy transforms into kinetic energy due to frictional forces acting against the motion. This frictional force can be defined as:

F_friction = μN

where ‘μ’ is the coefficient of friction and ‘N’ is the normal force. In most cases, the normal force can be calculated from the mass and the inclination of the plane, typically given as:

N = mg cos(θ)

By combining these equations, we can establish a relationship between the energies involved, offering a route to isolate the coefficient of friction. For a more precise calculation, one can apply the work-energy theorem, which states the work done by friction is equal to the change in kinetic energy of the block:

Work_done = F_friction * d,

where ‘d’ is the distance traveled along the incline. Therefore, we can express work done against friction as:

Work_done = μ(mg cos(θ)) * d.

This elucidation leads to the formulation linking friction into the conservation of energy equation:

mgh_initial = KE_final + Work_done.

Rearranging the terms provides:

μ = (mgh_initial – 0.5mv^2) / (mg cos(θ) * d).

Thus, by measuring the initial height, the distance traveled along the incline, and the final velocity of the object, one can determine the coefficient of friction. This methodology not only seamlessly integrates the notion of energy conservation but also enhances one’s ability to conceptualize the frictional force at play.

To extend the experiment’s complexity, one may consider variations in surface materials, incline angles, and object masses. Each variable introduces new dimensions of inquiry that will yield insights into the nature of friction. For instance, experimenting with different materials can lead to surprising results that demonstrate how surface texture and composition play significant roles in friction coefficients. Furthermore, varying the incline can help elucidate how gravitational forces impact the friction experienced by objects.

The practical aspect of this inquiry encourages curiosity-driven learning. Students become actively engaged as they adjust variables and measure outcomes, cultivating not only a deeper understanding of friction but also a solid grasp of energy conservation principles. Empowering learners to witness firsthand the interplay between forces transforms abstract concepts into tangible experiences.

Moreover, safety precautions should always be paramount during these experiments. Ensuring stable setups and employing appropriate protective measures will ensure that the exploration of friction remains both educational and secure. Communicating these safety protocols alongside experimental design fosters a responsible mindset in budding physicists.

In conclusion, utilizing the conservation of energy to discover friction offers a fresh and illuminating perspective on this crucial concept in physics. The integration of theoretical principles with practical execution encourages an inquisitive mindset while laying a strong foundation for more advanced studies. As engagement with these experiments deepens, students and educators alike will find themselves better equipped to appreciate the subtleties of friction—a seemingly ordinary force with extraordinary implications. This methodology not only enriches the educational experience but also invites participants to continue exploring the intricate tapestry of physical laws that govern our world.