Understanding the intricacies of energy conservation in angular dynamics poses an intriguing challenge: how can one discern whether energy is conserved in various systems? This question leads us to delve into the principles that govern rotational motion and the characteristics of energy within such frameworks. As we explore angular problems, it is essential to grasp the fundamental concepts and methods that allow us to analyze energy conservation effectively.

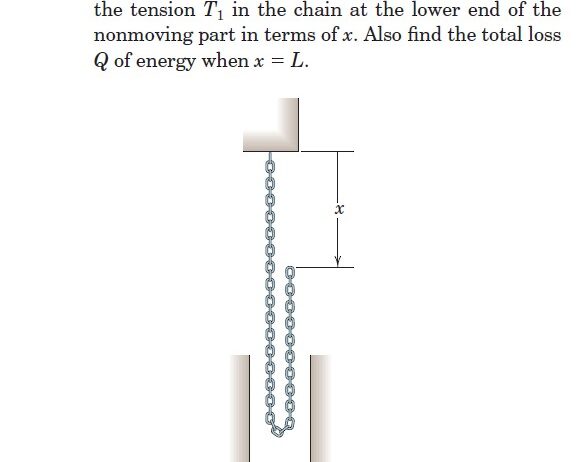

Angular problems often evoke images of pinwheels or spinning tops, yet they encompass a broader array of phenomena. When tackling these issues, two principal types of energy come into play: kinetic energy and potential energy. Kinetic energy, in the context of angular motion, is represented as ( KE = frac{1}{2} I omega^2 ), where ( I ) is the moment of inertia and ( omega ) is the angular velocity. On the other hand, gravitational potential energy is critical in scenarios involving height changes, described by ( PE = mgh ), where ( m ) is mass, ( g ) is the acceleration due to gravity, and ( h ) is the vertical height from a reference point.

But what does it mean for energy to be conserved? In the realm of physics, energy conservation implies that the total energy within a closed system remains constant over time, even as it transforms between different forms. When analyzing angular problems, it is vital to recognize if the system is isolated—meaning no external torques or forces are acting on it. This isolation is key to determining energy conservation.

To effectively analyze whether energy is conserved, one must consider the types of forces at play. Forces can broadly be categorized as conservative or non-conservative. A conservative force, such as gravity, does not dissipate mechanical energy as heat or sound, enabling energy conservation. Conversely, non-conservative forces, like friction, dissipate energy, leading to a loss in the total mechanical energy of the system.

Now, let’s pose a playful scenario: Imagine a pendulum swinging back and forth. At the apex of its swing, all energy is potential—gravitational potential energy is maximized, while kinetic energy is nullified. As it descends toward the lowest point, potential energy transforms into kinetic energy. At the nadir of the swing, kinetic energy is maximized, and potential energy is at its minimum. If no external forces, such as air resistance or friction at the pivot, intervene, energy remains conserved throughout the entire motion.

Conversely, consider a case where friction is present, perhaps due to the pendulum’s string rubbing against a surface. The energy lost to friction dissipates as thermal energy, indicating that not all mechanical energy remains within the system. Consequently, energy is not conserved in this scenario. Here lies the challenge: can you identify the presence of non-conservative forces in various angular problems?

As we proceed, let’s employ a systematic approach to determining energy conservation in angular situations.

- Step 1: Identify the System and Forces – Begin by delineating the system you are analyzing. Are external forces acting on your system? Are these forces conservative or non-conservative?

- Step 2: Define Energy Forms – Recognize the forms of energy present in the system. Will kinetic energy and potential energy be the primary focuses, or are there other forms, such as elastic energy, that need to be considered?

- Step 3: Construct Energy Equations – Write equations for the different states of the system. Apply the principles of conservation of energy to relate these equations. Are they equivalent?

- Step 4: Analyze Energy Transformation – Trace the transformations of energy throughout the system. At critical points—such as maximum height or lowest descent—evaluate whether total energy remains unchanged.

- Step 5: Assess for Losses – If discrepancies arise between initial and final energy, investigate potential energy losses due to non-conservative forces. This analysis will reveal whether energy is indeed conserved in practice.

When confronted with complex angular challenges, integrating rotational dynamics principles with energy analyses proves invaluable. Utilizing the moment of inertia, for example, allows a deeper understanding of how mass distribution affects a body’s resistance to angular acceleration and influences energy characteristics. The moment of inertia varies with the object’s shape and mass distribution, significantly affecting the kinetic energy dynamics of the system.

Furthermore, considering rotational analogs to linear motion—such as torque in place of force—can enhance one’s comprehension of angular systems. Torque, defined as ( tau = rF sin(theta) ), encapsulates the influence of distance and angle of force application on an object’s rotation, intimately intertwining with angular momentum. The conservation of angular momentum (expressed as ( L = I omega )) further validates energy conservation in closed systems, reaffirming the principle that energy cannot create or destroy but merely transforms between forms.

In conclusion, discerning whether energy is conserved in angular contexts requires a meticulous examination of forces and energy transformations within a given system. Identifying the character of external influences, assessing energy forms, and understanding the role of torques and moments of inertia are pivotal. As you tackle various angular problems, remember this systematic approach. It not only clarifies energy dynamics but also enhances your ability to navigate the fascinating challenges presented by angular motion. Seek the balance and recognize the principles at play, as understanding energy conservation will reinforce your grasp of the fundamental forces that shape our physical world.