When engaging with the intriguing dynamics of energy conservation, particularly within the realm of physics, a thought-provoking question arises: Is energy conserved in perfectly inelastic collisions? Such collisions offer a fascinating study of how kinetic energy and momentum interact in seemingly chaotic scenarios. To appreciate the answer to this question, it becomes imperative to first delineate what is meant by perfectly inelastic collisions.

A perfectly inelastic collision is characterized by the clinging together of two colliding bodies post-impact. This means that the objects do not just collide and bounce apart; instead, they move as a single entity after the collision occurs. This quality significantly affects energy transfer and the principles of conservation at play. In examining this unique type of collision, we encounter several fundamental concepts: momentum, kinetic energy, and the laws of thermodynamics.

To begin with, one must acknowledge that while momentum is conserved in all types of collisions, including perfectly inelastic ones, kinetic energy does not exhibit the same behavior. This leads us to the crux of our exploration. In a perfectly inelastic collision, although total momentum before and after the event remains constant (as per the law of conservation of momentum), kinetic energy dissipates. The energy is not destroyed; rather, it is transformed into other forms, such as thermal energy, sound energy, and sometimes even deformation energy in the involved materials.

Imagine this scenario: a moving truck collides with a stationary car at an intersection. After the collision, both vehicles crumple and adhere to one another, eventually moving together as a single mass. The truck, with its given momentum, transfers some of its energy to the car, resulting in both vehicles moving at a lower combined velocity than the truck’s initial velocity alone. During this process, a significant portion of the kinetic energy is transformed – the sound of the impact, the heat generated in the crumpling metal, and the energy lost to internal friction within the materials are all manifestations of energy transformation, not conservation.

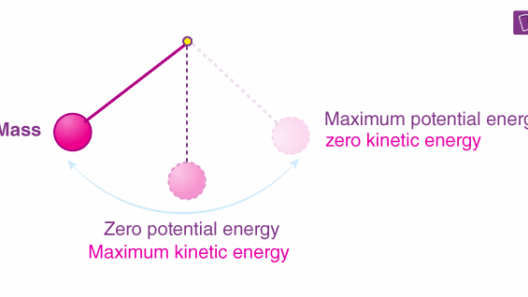

You may wonder: if energy appears to be lost in the context of kinetic energy, does this mean it is gone forever? The short answer is no. In the grand tapestry of physics, energy is perpetually transformed rather than obliterated. Thus, while the kinetic energy diminishes during a perfectly inelastic collision, it transmutes into forms suitable to the circumstances surrounding the collision. This reinforces a critical tenet of the conservation laws: energy can shift forms but cannot simply vanish.

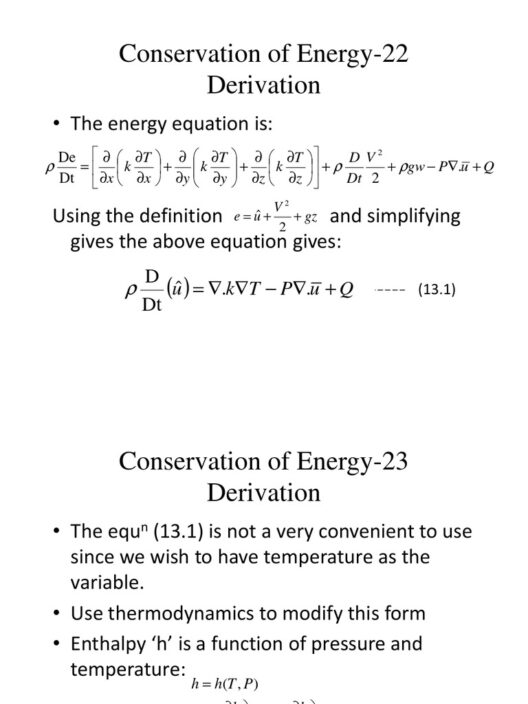

Further elucidating this concept, let us consider equations that express momentum and kinetic energy. The momentum ((p)) of a system can be stated as the product of mass ((m)) and velocity ((v)), expressed as (p = mv). As momentum is conserved, we can analyze what occurs before and after the event. If two bodies collide, say body 1 with mass (m_1) and initial velocity (v_1) and body 2 with mass (m_2) and initial velocity (v_2 = 0), the conservation of momentum can be represented as follows:

(m_1v_1 + m_2v_2 = (m_1 + m_2)v_f), where (v_f) is the final velocity of the combined mass post-collision.

On the other hand, kinetic energy ((KE)) is expressed as (KE = frac{1}{2}mv^2). During a perfectly inelastic collision, one would note the initial kinetic energies of the two bodies are:

(KE_{initial} = frac{1}{2}m_1v_1^2 + frac{1}{2}m_2v_2^2) and the final kinetic energy becomes (KE_{final} = frac{1}{2}(m_1 + m_2)v_f^2).

The disparity between (KE_{initial}) and (KE_{final}) illustrates the loss of kinetic energy, leading to the conclusion that not all of the kinetic energy before the collision is retained after the collision.

This brings us to the realm of implications. Understanding that kinetic energy is not conserved in perfectly inelastic collisions has far-reaching ramifications, especially in the context of engineering and safety design. Automotive safety features, for instance, are precisely engineered with this principle in mind. Crumple zones in vehicles are designed to absorb energy during a collision, ensuring the dissipation of force away from passengers. In this light, the physics of energy transformation permeates our daily lives, often unrecognized yet profoundly impactful.

In conclusion, while a perfectly inelastic collision presents as a captivating episode of momentum conservation, it simultaneously stands as a reminder of the intricacies surrounding energy conservation. The transformation of kinetic energy into other energy forms underscores the broader scientific principle that energy neither evaporates nor ceases to exist. Instead, it morphs into different expressions depending on the system’s parameters and conditions. This insight not only enriches our comprehension of physical interactions but also places emphasis on the significance of energy design and management in our technological world.

As such, we return to the fundamental inquiry: Is energy conserved in perfectly inelastic collisions? Yes and no; energy transforms and is conserved in totality, yet its kinetic iteration diminishes. This interplay of momentum and energy invites continued curiosity and exploration—fostering a deeper understanding of the very fabric of our universe.