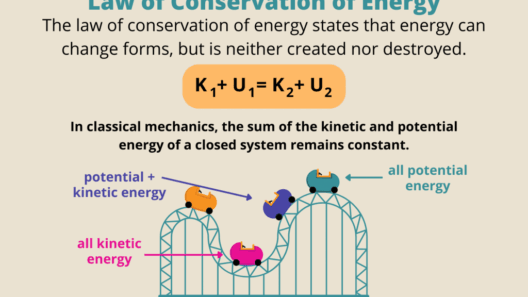

The concept of conserved energy, often encapsulated in the phrase “cost of conserved energy” (CCE), embodies a pivotal metric in the dialogue surrounding sustainability and energy efficiency. Understanding the nuances of CCE is essential for both policymakers and individuals concerned about environmental stewardship. This treatise endeavors to elucidate what constitutes the cost of conserved energy, its implications for sustainability, and its broader significance within contemporary environmental discourse.

At its core, the cost of conserved energy is defined as the cost incurred to save a unit of energy through efficiency measures, rather than through conventional electricity production. This metric serves as a benchmark, allowing stakeholders to assess the relative economic feasibility of energy-saving interventions compared to investing in new energy generation. An example might illuminate this concept: if a utility company invests in retrofitting buildings with energy-efficient technology, the resultant energy savings can be compared against the expenses associated with constructing a new power plant. If the CCE of energy efficiency measures is lower than the cost of new power supply, then a compelling case for conservation emerges.

As global enthusiasm for renewable sources burgeons, the significance of CCE becomes increasingly salient. Renewable energy resources, such as wind, solar, and hydroelectric power, are essential to ensuring a sustainable future. However, the intermittency and unpredictability of these sources necessitate the implementation of efficient energy use strategies. By focusing on CCE, stakeholders can prioritize investments that yield substantial energy conservation, effectively bridging the gap between renewable energy production and consumption.

The factors influencing the cost of conserved energy are multifaceted. Initially, one must consider the technological aspects. Different energy-saving technologies exhibit divergent efficiencies, initial costs, and lifespans. For instance, LED lighting typically presents a far lower CCE compared to incandescent bulbs due to its superior energy efficiency and longevity. Furthermore, innovations in materials science and engineering continue to facilitate the development of technologies that minimize energy waste across various sectors. Building insulation advancements, smart home technologies, and industrial process improvements represent exemplary areas where lower CCE can be achieved.

Financial elements also influence CCE. Initial capital investments, operation and maintenance costs, and potential financial incentives all play a role. Community-based initiatives, government subsidies, and tax rebates can significantly mitigate upfront expenditures, rendering conservation efforts more attractive. Notably, the intrinsic value of energy savings over time must be assessed, factoring in inflation and fluctuating energy prices. Life cycle analysis (LCA) becomes indispensable in this evaluation, as it provides a comprehensive view of the total costs and benefits associated with energy efficiency projects.

Environmental considerations are equally paramount when discussing the cost of conserved energy. The repercussions of excessive energy consumption extend beyond mere economic metrics; they resonate through ecosystems and human communities alike. Pollutants emitted from fossil fuel energy sources contribute vastly to climate change, air quality degradation, and a myriad of health issues. Each unit of conserved energy mitigates these adverse effects, elucidating the intrinsic value of energy efficiency in combatting environmental degradation. CCE thus not only encompasses a financial component but also integrates an ecological perspective, highlighting the interdependency between energy consumption patterns and environmental health.

An indispensable element in this discourse is the concept of ‘energy equity.’ As the pursuit of sustainability gains momentum, a recognition of diverse community needs becomes critical. The cost of conserved energy may manifest variably across socio-economic strata, necessitating tailored approaches that prioritize vulnerable populations. Effective dialogues centered around energy affordability must ensure that low-income households are not disproportionately burdened by the transition towards energy efficiency. Policymakers must strive to align conservation measures with equity frameworks, ultimately fostering a just transition in energy systems.

Education and public engagement are vital to fostering a culture of energy conservation. Increasing awareness of the cost of conserved energy encourages individuals and businesses to embrace conservation practices. Campaigns that elucidate the benefits of energy efficiency promote collective action and engender community buy-in. Programs targeting behavioral change—such as energy audits provided by local utilities—can empower users to make informed decisions about their energy consumption patterns. The role of education in transforming societal norms around energy use cannot be overstated; it is a foundational component of sustaining momentum towards a more energy-conscious society.

In conclusion, the cost of conserved energy encapsulates a critical intersection of economic, environmental, and social factors in the narrative of sustainability. It illustrates how energy efficiency can serve as both a pragmatic solution and a moral imperative in the face of escalating environmental challenges. As localization of policies and rapid advancements in technology continue to shape the climate agenda, a thorough comprehending of CCE will equip stakeholders to innovate wisely, maximize benefits, and propel societies towards holistic energy sustainability. The multifaceted nature of CCE suggests that its exploration is not merely a technical endeavor but a holistic journey towards a more sustainable and equitable future for all.