As we delve into the intricate interplay between land and sea, one profound observation emerges: global temperatures are rising at staggeringly different rates across these two critical domains. This discrepancy demands a comprehensive examination, revealing not just the immediate implications of climate change but also the underlying mechanisms contributing to this phenomenon. Understanding where global temperatures rise faster is crucial for crafting effective responses to the ongoing environmental crisis.

It is widely acknowledged that global warming, primarily driven by anthropogenic activities, has led to a steady increase in average temperatures. However, what is less understood is the differential warming observed between terrestrial and marine environments. Researchers have documented that, in many regions, land temperatures tend to rise more rapidly than those of the ocean. But why does this discrepancy exist?

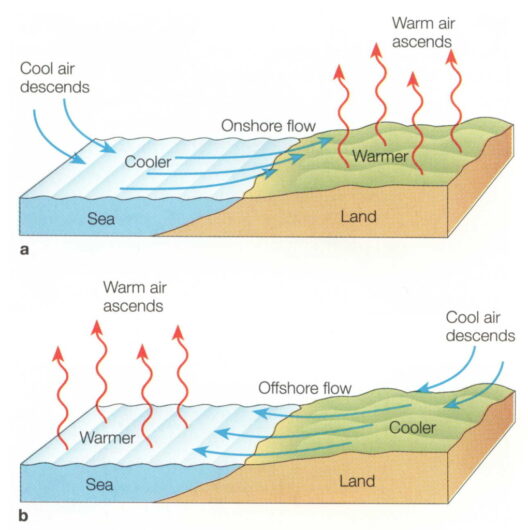

One of the primary reasons for this phenomenon lies in the physical properties of land and water. Land surfaces absorb heat more readily than oceans, which possess a higher thermal inertia. This means that land warms up quickly during periods of increased solar irradiance, such as summer months. Conversely, oceans mitigate temperature increases due to their vast volumes and the specific heat capacity of water, which allows it to retain heat without significant changes in temperature.

Furthermore, the unique characteristics of land surfaces also contribute to differential warming. Urbanization plays a significant role in land temperature increases. Cities are often composed of materials such as concrete and asphalt that have high heat retention properties. This urban heat island effect exacerbates temperature rises, accelerating warming trends in metropolitan areas compared to their surrounding rural counterparts.

Climate feedback mechanisms further complicate our understanding of how and where temperatures increase. As land surfaces warm, they can lead to alterations in vegetation patterns and soil moisture levels. These changes, in turn, can influence local weather phenomena, such as alterations in precipitation and humidity, creating a feedback loop that intensifies warming. For instance, reduced soil moisture can not only elevate temperatures but also contribute to more severe drought conditions, exacerbating the impacts of climate change.

On the other hand, the oceans are not impervious to the effects of climate change. While they are warming at a slower pace on average, the consequences of this melting are severe. Ocean temperatures affect marine ecosystems, including coral reefs, which are particularly sensitive to temperature variations. The phenomenon of coral bleaching—a stress response of corals to higher sea temperatures—has become more prevalent, jeopardizing biodiversity and disrupting marine food webs.

The impact of temperature rise is not uniform across oceanic regions. Polar waters are experiencing rapid warming due to climate change, significantly altering marine ecosystems and weather patterns. The Arctic, in particular, is warming at nearly twice the global average rate, resulting in significant ice melt and habitat loss for species dependent on these frigid environments. This has broader implications for global climate systems, as the cryosphere plays a critical role in regulating Earth’s temperature.

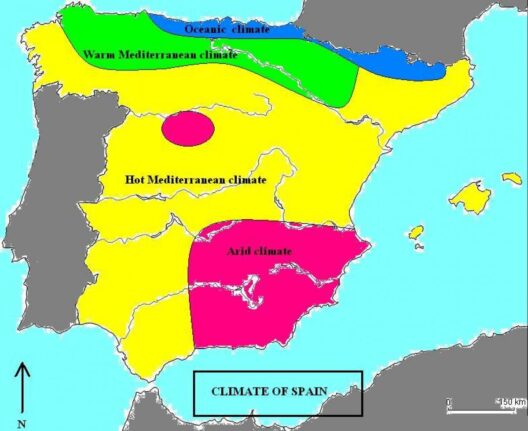

Interestingly, the geographical disparities in warming rates evoke a fascination that transcends mere facts and figures. They invoke a deeper understanding of ecological interconnectedness. For instance, elevated land temperatures can influence atmospheric currents and precipitation patterns, impacting weather systems even in distant oceanic regions. This interconnectedness highlights how environmental changes in one domain—whether terrestrial or marine—can resonate throughout the global ecosystem.

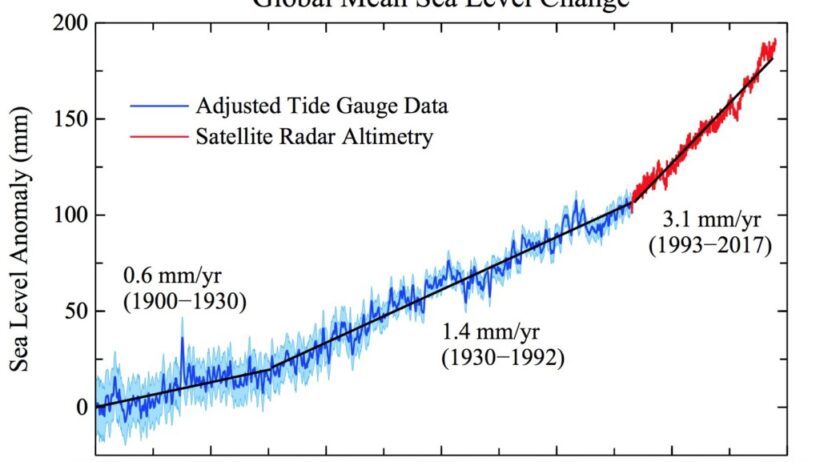

Furthermore, this discussion urges us to consider the societal ramifications of varying temperature increases. Regions that experience rapid land temperature rises may face heightened risks of heat-related illnesses, reduced agricultural productivity, and increased energy demands for cooling. In contrast, coastal communities may grapple with sea-level rise and the accompanying threats to infrastructure and livelihoods. A comprehensive understanding of these differing impacts is essential for developing strategies that protect vulnerable populations and promote resilience.

In addressing the challenge of climate change, acknowledging these differences in warming rates is imperative for policymakers and advocates alike. Mitigation strategies must consider both land and sea, as solutions that focus exclusively on one domain risk neglecting the interconnected challenges posed by climate change. Coastal restoration programs, renewable energy initiatives, and sustainable agricultural practices can all contribute to a holistic approach to climate resilience.

The urgent need for climate action is underscored by the ongoing changes in our environment. The rising temperatures on land and the alarming warming of the oceans present a stark reminder of the finite nature of our planet’s resources. As stewards of the Earth, it is our responsibility to mitigate these impacts through intentional and informed actions that consider both local and global contexts.

In conclusion, the question of where global temperatures are rising faster—land or sea—is not merely one of scientific curiosity. It is a critical inquiry into the mechanics of climate change and its multifaceted impacts on the world we inhabit. The intricate tapestry woven by differential warming illustrates the need for comprehensive strategies that bridge the terrestrial and marine narratives. As we confront the climate crisis, understanding these dynamics will be fundamental to ensuring a sustainable future for generations to come.