The issue of climate change is at the forefront of global discourse, prompting an array of questions about the sources of greenhouse gas emissions. One curious question that occasionally arises is whether human flatulence contributes significantly to global warming via methane emissions. This inquiry serves as an entry point to understanding methane’s role in climate change, its sources, and the common misconceptions surrounding this potent greenhouse gas.

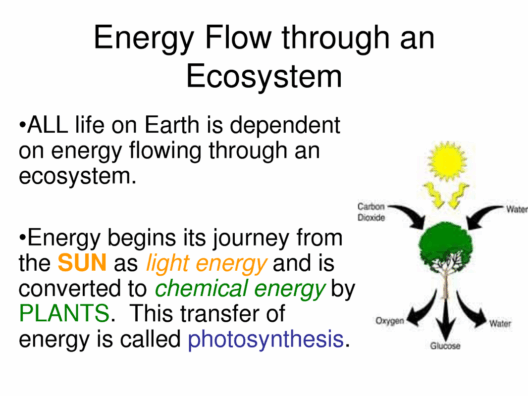

Firstly, it is essential to grasp the basics of methane itself. Methane (CH4) is a hydrocarbon that is considerably more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide (CO2), with a global warming potential approximately 25 times greater over a 100-year period. Although methane persists in the atmosphere for a shorter duration than CO2—approximately ten years before it oxidizes into carbon dioxide and water vapor—the urgency of its impact is undeniable. This creates a pressing concern about methane emissions coming from both natural and anthropogenic sources.

When discussing methane emissions from humans, it is pivotal to understand the primary sources. The biological process of digestion, particularly involving the bacteria within the intestines, generates methane during the breakdown of food. Thus, human flatulence does emit methane, but its overall contribution is relatively insignificant when compared to other sources. For instance, livestock, particularly ruminants like cows and sheep, produce considerable methane through enteric fermentation, which occurs during their digestion process. Estimates suggest that livestock contribute approximately 30-40% of total anthropogenic methane emissions.

Beyond livestock, landfills are another substantial source of methane. When organic waste decomposes anaerobically (without oxygen), it generates methane, making landfills a focal point for efforts to capture and manage methane emissions. Furthermore, the oil and natural gas industry contributes significantly to methane emissions, with methane leaks and flaring practices exacerbating the situation. These sources culminate into a substantial methane emission profile, far overshadowing the emissions attributable to human flatulence.

Consequently, while humans do produce methane through flatulence, it is crucial to contextualize this within the broader spectrum of methane sources. Research estimates that the average human generates approximately 0.01 to 0.1 liters of methane per day through digestion. On a global scale, this emits around 0.1 to 0.2 teragrams (1 teragram = 1 trillion grams) of methane annually. In contrast, livestock methane emissions reach hundreds of teragrams per year, registering as a dominant factor in methane’s contribution to climate change.

This discussion raises questions surrounding the sheer volume of methane impacting global warming. While specific methane emissions from human beings may be minuscule, myths proliferate as to the magnitude of their contribution. Many people might exaggerate the potential impact, attributing undue blame on flatulence when considering climate change’s multifactorial causes.

Additionally, public perception of methane may be further muddled by media portrayals which often sensationalize the impacts of natural gas extraction methods, linking it to everyday human activities in a misleading manner. It is essential to differentiate between casual anthropogenic emissions—such as those from human digestive processes—and major contributors like agricultural practices and fossil fuel extraction.

Sustainable practices aimed at methane reduction should focus predominantly on large-scale emission sources. Initiatives could include improving livestock feeding practices, developing more efficient waste management systems, and advancing technologies in the oil and gas industry to minimize leaks. Advocating for dietary changes, such as reduced meat consumption, can also play a vital role in lowering methane emissions, given the significant contribution from livestock production.

Moreover, awareness and education around these issues could drive community-level action on sustainability. Projects promoting composting and recycling, which minimize methane emissions from landfills, can harness cooperative efforts for significant impact. This collective movement can be instrumental in enlivening the discourse surrounding climate change and empowering individuals to enact change.

Another layer to consider is the role of consumer behavior in a carbon-centric economy. By opting for plant-based diets and supporting sustainable agricultural practices, consumers can directly influence methane emissions linked to livestock. Furthermore, encouraging regenerative agricultural techniques not only aids in carbon sequestration but can also minimize methane generation from farming processes.

In conclusion, although human flatulence does indeed release methane—a potent greenhouse gas—its contribution to global warming is negligible when placed alongside other significant sources. The focus must remain on understanding the grander scale of methane emissions and their implications for climate policy and personal behavior. By educating ourselves and promoting sustainable choices, each individual can meaningfully participate in mitigating climate change, while also dispelling myths that divert attention from the greater challenges at hand. Ultimately, addressing climate change requires holistic thinking and a commitment to collective solutions rather than isolating individual factors in the complex web of environmental impact.