Global warming, a term that has become synonymous with the climate crisis, engenders a myriad of questions, some of which reside in the realm of paradox. One of the most provocative inquiries is whether this phenomenon could paradoxically trigger an ice age. At first glance, such an assertion seems contradictory; can the warming of our planet conjure the ominous specter of glacial expansion? To grasp this conundrum, we must delve into the intricate relationship between global warming and the complex systems governing our climate.

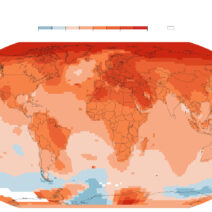

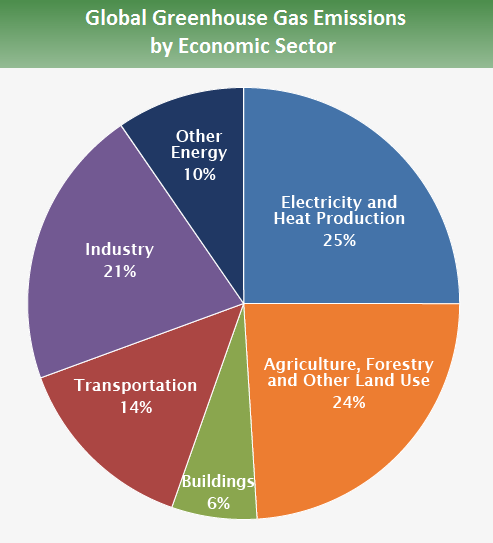

To comprehend the potential for an ice age in a warming world, it is essential to understand the mechanics of Earth’s climatic systems. The planet’s climate is not a simple thermostat, adjusting uniformly in response to increased greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, it functions as a multifaceted machine composed of countless moving parts, each influencing the other in complex ways. Global temperatures are on the rise due to unprecedented levels of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Yet, this warming could disrupt the delicate balance of oceanic currents, atmospheric patterns, and polar ice masses, potentially setting the stage for a dramatic climatic pivot.

The earth’s atmosphere acts as a protective blanket, trapping heat from the sun. However, when this balance is altered—particularly through increased freshwater influx into the ocean—destructive feedback loops can emerge. One of climate change’s most pernicious manifestations is the melting of polar ice caps. As the Arctic ice recedes, vast amounts of freshwater flow into the ocean. This influx disrupts the thermohaline circulation, a critical component of the global climate system that regulates temperature and weather patterns. The modification of this system could lead to a pyrotechnic interplay of warming in some regions while triggering cooling in others.

In scientific terms, the “Great Ocean Conveyor Belt” is integral to global temperature regulation. This vast network of ocean currents circulates warm water from the equator toward the poles and cold water from the poles back toward the equator. A significant disruption in this circulation could initiate a cascade of climatic changes. Regions such as Western Europe, which currently benefit from relatively mild winters due to warm ocean currents, could find themselves entrapped in a new ice age scenario if this circulation were to slow or collapse entirely.

The concept of a ‘flipped coin’ metaphor aptly captures the dichotomy within climate models. On one side, rising global temperatures could lead to more extreme heatwaves, droughts, and devastating wildfires. On the flip side, altered ocean currents might plunge certain areas into frigid conditions, akin to a coin landing tails up in the midst of a climate crisis. This duality reinforces the idea that while overall trends predict a warming planet, regional anomalies could starkly diverge from that trajectory.

Historical records reveal that such dramatic climatic shifts are not mere theoretical fancies. The Earth has experienced glacial and interglacial periods throughout its history, often pivoting on slight variations in solar radiation and atmospheric composition. The Younger Dryas, for instance, was a significant cooling event that occurred about 12,900 years ago, attributed to disruptions in oceanic currents amid a warming period. This historical precedent implies that abrupt climate transitions are not only possible but indeed probable as the planetary balance continues to wobble under the weight of anthropogenic influences.

The potential for another ice age resulting from global warming also fosters a chilling realization: climate change is fundamentally non-linear. Its effects do not manifest uniformly or predictably. Rather, the system can experience sudden shifts, potentially leading to unforeseen and devastating consequences. The risk resides in the unpredictable feedback loops that climate scientists continue to explore. Melting permafrost, for example, releases greenhouse gases previously trapped, exacerbating warming. This interplay between melting ice and gaseous release exemplifies the tightrope on which our climate delicately balances.

Disturbingly intriguing is the possibility that climate change could spawn weather phenomena akin to the “polar vortex.” This meteorological event, characterized by a strong, circular wind pattern around the polar region, can weaken due to warming, allowing frigid Arctic air to spill into temperate regions. The paradox deepens: the very systems designed to keep certain areas warm might become reined in by the chaotic dynamics of climate change, fostering conditions reminiscent of an ice age.

As we venture further into the uncharted waters of anthropogenic climate disruption, the concept of a new ice age conjures an eerie image of a world at the brink. Our reliance on fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes not only warms our planet but potentially destabilizes it enough to usher in widespread climatic anomalies. If humanity continues on its current trajectory, we may be left with a tarnished legacy: one where the titanic forces of nature, once thought to be predictable, shift with breathtaking dramaticism.

In contemplating whether global warming could lead to an ice age, one must sift through the complexities of climate systems like a watchmaker examining the cogs of an intricate timepiece. Time is of the essence; turning a blind eye to the undeniable signals presented by our planet is no longer an option. Humanity stands at a crossroads. We must act decisively to mitigate the looming threat of warming, with an understanding that the consequences of inaction might unfurl into scenarios we cannot yet conceive.

Ultimately, the relationship between global warming and the potential for an ice age is a twofold entanglement of hope and trepidation. The planet’s ability to regulate its climate may be disrupted by our processes, yet it also presents an opportunity for humanity to engage with its environment, fostering greater respect for our natural world. By recognizing the profound interconnectivity of global systems, we may yet navigate through the uncertain future, heralding an era of sustainability rather than inertia.