Understanding the trajectory of global warming is akin to deciphering a complex tapestry woven from countless threads of data, scientific analysis, and environmental change. This intricate weave reveals a compelling narrative of our planet’s climatic evolution. The 2000s were a particularly contentious period in this narrative, marked by debates surrounding the perceived slowdown of global warming. In this examination, we will delve deep into the data and analyses that inform our understanding of climate change during this pivotal decade.

To begin, it’s essential to establish the baseline: the Earth’s average temperature has been inexorably climbing for over a century. This phenomenon is primarily driven by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, created largely by the combustion of fossil fuels and land-use changes. The early 2000s, however, presented a peculiar anomaly that sparked widespread debate. Scientists noted a lull in the rate of temperature increase, which many dubbed a “hiatus” in global warming. But what did the data truly reveal during this time?

When examining the surface temperature records, the first thing that stands out is the duality of observations—short-term fluctuations against long-term warming trends. Proxy datasets such as ice core samples, ocean heat content measurements, and satellite observations indicated something unexpected: a period of relatively flat temperature anomalies between 1998 and about 2012. The debate intensified as various factions emerged. Some scientists posited that this slowdown indicated a fundamental issue with climate models, while others contended that it was merely a temporary variability inherent to climate systems.

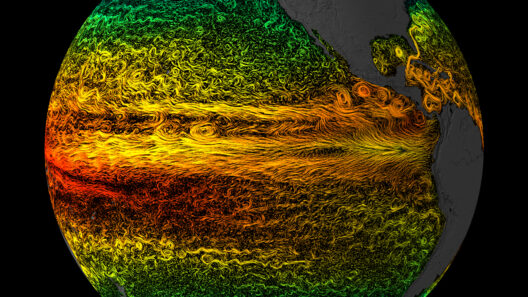

An examination of oceanic influences is critical here. By looking beneath the surface, we find that the oceans absorb nearly 90% of the excess heat from global warming, acting as both a buffer and a contributor to climate regulation. During the 2000s, the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and prolonged changes in the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) influenced surface temperatures. The presence of a particularly strong El Niño in 1998 contributed to an immediate spike in temperatures, creating a baseline that seemed anomalous. The ensuing years, characterized by La Niña events, cooled the surface temperature, thus giving the illusion of a slowdown. Nevertheless, deeper oceanic layers were still accumulating heat, suggesting that the planet was far from cooling.

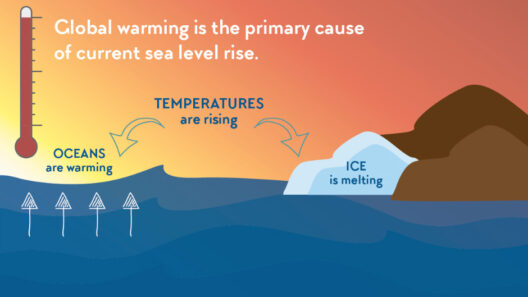

To comprehend the nuance of this alleged slowdown, one must also grapple with the concept of climate variability versus climate change. The natural variability of climate—due to volcanoes, solar cycles, and ocean currents—can obscure long-term trends. This complex interplay can create periods where warming appears to decelerate, but it does not negate the overall upward trajectory that is supported by century-long data sets. The apparent lull can be likened to a forest where new growth appears stunted due to drought; beneath the surface, roots are still drawing sustenance.

Moreover, short-term datasets can be deceptive. The focus on individual years, particularly those driven by short-lived climatic phenomena, can skew perceptions of broader trends. A single decade cannot encapsulate the entirety of Earth’s climatic dynamics. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) consistently emphasizes that examining climate change requires an approach absent of cherry-picking data. Instead, researchers advocate for a holistic view—one that considers long-term averages and trends, dispelling myths that may surface from more paltry data reflections.

In exploring the implications of this context, one must also acknowledge the significant advancements in climate science during this era. The 2000s saw considerable improvements in satellite technology and climate modeling, allowing for more nuanced understanding and prediction of future warming scenarios. Nevertheless, the perception of a hiatus led to distraction, ultimately fueling climate skepticism—an impediment that continues to echo through discussions on policy and public perception. It’s essential to recognize that even if fluctuation exists, the broader narrative rarely deviates from the path of long-term warming reinforced by human activity.

Yet, climate discourse is not solely one of data; it is immensely intertwined with sociopolitical dynamics. The slowed temperature increases were seized upon by various interest groups as empirical evidence for climate change denial. This has profound implications for policy-making. When evidence is manipulated or misinterpreted, the weight of scientific consensus can be undermined. Thus, the discourse shifts from one of proactive climate solutions to defensiveness, encapsulating a crucial pivot away from meaningful action.

In conclusion, while the 2000s presented a puzzling chapter within the intricate script of climate science, it is vital to navigate these waters with both vigilance and clarity. The purported slowdown in global warming during this decade does not suggest an end to the escalating threat of climate change; rather, it highlights the importance of continued research. Future generations must wrestle with the specter of climate change armed with a comprehensive understanding of data, complexity, and the intertwining of atmospheric and oceanic systems. The narrative of global warming is far from linear, but the persistent climb remains disturbingly clear: we are on a trajectory that demands urgent attention and commitment to address the looming climate crisis.