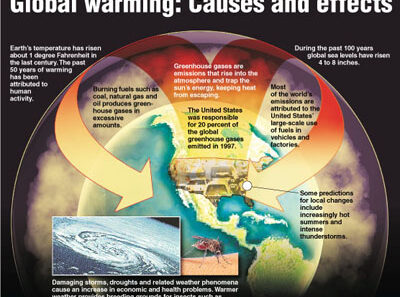

The discourse surrounding global warming has transcended geographical boundaries, yet regional perspectives, particularly from Asia, illuminate the multifaceted nature of this pressing issue. The intricacies of climate science evidence a consensus among climatologists on the existence of global warming, but the nuances of its implications and solutions vary significantly across the continent. This essay endeavors to unravel the complexities of Asian climatological consensus on climate change, offering an overview while simultaneously delving into the underlying factors that shape the opinions within this vast region.

To commence, it is paramount to recognize that Asia encompasses a diverse array of nations, each possessing their unique landscapes, climates, and socio-economic structures. This diversity inevitably influences the perspectives of scientists and climatologists regarding global warming. Countries such as Japan and South Korea, equipped with robust research infrastructures, often align their findings with overarching global scientific narratives. Conversely, developing nations, such as Bangladesh or Vietnam, face existential threats from rising sea levels, drawing their focus toward immediate adaptive strategies rather than theoretical debates.

There is a prevailing agreement among Asian climatologists that climate change is a veritable phenomenon, supported by a myriad of scientific evidence. A joint report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted alarming temperature increases throughout Asia, reinforcing the notion that warming trends are not only an abstract idea but a palpable reality confronting many nations. This consensus is underpinned by observable phenomena: glacial retreat in the Himalayas, increasingly erratic monsoon patterns, and rising coastal salinity affecting agriculture, particularly in nations highly dependent on agrarian economies.

However, one can observe a divergence when it comes to the interpretation of these findings and the proposed solutions. Wealthier Asian nations, with greater financial resources and technological advancements, tend to advocate for ambitious carbon reduction targets and the adoption of sustainable energy technologies. In contrast, poorer nations, heavily reliant on fossil fuels for economic growth, face a dilemma: pursuing development while mitigating environmental impacts. This schism can be traced to varying geopolitical realities and economic imperatives.

The exploration of climatological consensus extends beyond mere employment of data; it is intricately linked to cultural, historical, and political contexts. In Japan, for example, the traumatic experiences of natural disasters, including the Fukushima nuclear disaster, have bolstered public discourse around climate resilience and renewable energy adoption. The Japanese government has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions significantly by 2030, reflecting a broad societal acknowledgment of the urgency posed by climate change.

Conversely, nations like India grapple with the dual challenges of economic development and environmental sustainability. As one of the world’s largest emitters of carbon dioxide, India’s climatologists emphasize the need for a balanced approach. They advocate for thorough adaptations to climate impacts while simultaneously striving for economic growth, creating a nuanced perspective that recognizes the complexity of their situation. The discussions surrounding the International Solar Alliance epitomize efforts to forge a collective climate strategy among developing nations, showcasing a commitment to sustainable futures even amid economic constraints.

Delving deeper, one can discern that this layered perspective on climate change in Asia reflects a tacit acknowledgment of historical injustices. Many developing countries feel disproportionately affected by climate change, a crisis largely instigated by industrialized nations. This sentiment fuels a climate justice movement, asserting that developed nations bear a moral obligation to assist poorer counterparts. Climatologists from these nations often stand firm on the necessity for global equity in climate responsibility and finance, positioning themselves as advocates for a fair approach to carbon neutrality.

Moreover, the differing levels of awareness and education on climate issues within the Asian populace can influence how climatologists engage with and communicate their findings. In urban centers, where education levels may be higher, awareness of climate science is often reflected in public discourse and policy-making. However, in rural and remote areas, the immediacy of survival-based concerns can overshadow long-term environmental issues. Hence, climatologists face the formidable challenge of disseminating their work in an accessible manner, ensuring that their messages resonate, not only with policymakers but also with local communities that may feel the first and most severe impacts of climate change.

Furthermore, Asian climatologists are increasingly recognizing the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in tackling climate change. By collaborating with economists, sociologists, and indigenous knowledge keepers, the discourse surrounding climate change is evolving. This integration of diverse perspectives fosters a more holistic understanding of climate impacts, enabling tailored solutions that resonate with local contexts and cultural heritages.

In conclusion, while Asian climatologists broadly concur on the reality of global warming, their opinions diverge regarding its implications, solutions, and the strategies for effective communication with the public. This divergence stems from a tapestry of diverse socio-economic structures, historical contexts, and cultural lenses through which the climate crisis is interpreted. As climatologists continue to collaborate across borders, building bridges between scientific consensus and socio-economic realities, a unified approach to confronting climate change can emerge. Only through such collective efforts can we hope to navigate the complexities of global warming and its irreversible impacts on our planet.