As the specter of climate change looms larger, a poignant inquiry arises: do developed countries bear the most significant responsibility in combating global warming? This question provokes a complex tapestry of economic, historical, and ethical considerations that merit in-depth exploration. Developed nations, often armed with advanced technologies and substantial financial resources, are frequently perceived as being in the vanguard of environmental stewardship. However, a closer examination reveals that the interplay of historical emissions, economic capabilities, and social obligations shapes their role in the fight against climate change.

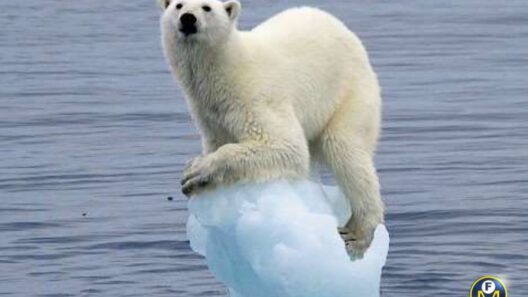

To delineate the responsibilities of developed countries, it is essential to contextualize their historical contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. Since the dawn of the industrial revolution, these nations have been the primary emitters of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. A significant proportion of today’s atmospheric CO2 can be attributed to industrial activities that originated in the West. Such emissions have engendered a myriad of environmental challenges that disproportionately affect vulnerable populations worldwide. Consequently, it is argued that developed countries possess a moral imperative to lead efforts toward mitigation and adaptation.

Moreover, the economic capability of developed nations amplifies their responsibility. With their vast resources, technological advancements, and robust infrastructure, these countries are well-positioned to implement ambitious policies aimed at reducing carbon footprints. For instance, investments in renewable energy technologies, sustainable urban planning, and public transportation systems can significantly curtail emissions. The financial clout of developed nations also affords them the opportunity to provide vital support to developing countries, which often struggle with the dual challenges of poverty and climate vulnerability. This nexus between wealth and responsibility cannot be overlooked.

In the arena of international climate negotiations, developed countries have often set the agenda. However, this leadership role should come with a concomitant accountability, particularly regarding commitments made under frameworks such as the Paris Agreement. The promise to limit global temperature rise is a collective one, yet the onus frequently falls heavier on those who have historically contributed more to the problem. This inequity can breed resentment among developing nations, which may perceive the actions of their more affluent counterparts as inadequate or self-serving. The notion of “climate justice” emerges as a critical discourse, advocating for equitable distribution of both the burdens and benefits associated with climate change mitigation.

Nonetheless, the argument that developed nations alone hold the lion’s share of responsibility can be overly simplistic. The dynamics of a globalized world reveal interconnectedness that complicates the attribution of guilt. Emerging economies, particularly in Asia and Latin America, have seen a rapid industrialization trajectory that has resulted in heightened emissions. Countries like China and India have become major contributors to global warming, leading to debates about the shared responsibility. The current landscape underscores that climate change is not merely a byproduct of individual national policies, but rather a complex global phenomenon that transcends borders.

Crucially, the path to sustainable development in developing nations must be acknowledged. Many of these countries aspire to modernize and uplift their populations, often leading to increased emissions in the short term. However, the context of such development is essential; the challenge lies in promoting green technologies that can facilitate economic growth without exacerbating environmental degradation. In this regard, developed nations have a unique role in fostering innovation and providing financial and technical assistance to ensure that developing countries can leapfrog outdated, carbon-intensive practices.

The intergovernmental efforts at addressing climate change exemplify the challenges inherent in collective action. The consensus necessary for effective global governance is often elusive amid diverse national interests and economic realities. Developed countries might have greater historical responsibility, yet their role must be effectively balanced with the agency of developing nations, allowing for a collaborative approach to climate action. This necessitates an engaged dialogue that takes into account national contexts while inspiring collective national ambitions.

The recent trends illustrate a growing movement among cities, states, and regions within developed nations to address climate change independently of their national governments. These subnational actors often initiate innovative policies and ambitious targets, showcasing leadership that at times eclipses that of federal administrations. This grass-roots momentum can serve as a powerful catalyst for broader change, illustrating that responsibility does not solely reside within the domain of the nation-state.

In conclusion, the responsibility of developed countries in the fight against global warming is profound and multifaceted. Historical emissions, economic capacities, and moral imperatives dictate their role in addressing climate change. Nevertheless, the global nature of the crisis calls for a broader dialogue that transcends the dichotomy of developed versus developing nations. Ultimately, the pursuit of a sustainable future demands cooperative action, transformative policies, and an unwavering commitment to climate justice across all nations. The time has arrived for an inclusive strategy that harnesses the strengths of each country, acknowledging that while developed nations may have a larger share of the historical burden, the path toward climate resilience belongs to all humanity.