Global warming is an intricate and pressing issue, one that has captivated the minds of scientists, policymakers, and the general populace alike. As this phenomenon gains more attention, the conversation has veered into quirky yet thought-provoking territory. Among the speculations, a perplexing question arises: Do human farts and breathing contribute to global warming? This query evokes a mixture of amusement and seriousness, prompting us to separate myth from fact.

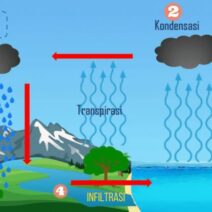

To commence with an introspective analysis, we must recognize that human activities emit greenhouse gases that significantly contribute to global warming. Common emissions stem from burning fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial processes. However, human physiology also plays a role. The gases exhaled during respiration and those produced through digestion can add to atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, albeit in substantially smaller quantities compared to industrial sources.

When we breathe, our bodies engage in a fundamental process—cellular respiration—in which oxygen is consumed, and carbon dioxide (CO2) is produced as a byproduct. It may be surprising to learn that approximately 420 billion tons of CO2 are exhaled by humans each year. While this number seems staggering, it pales in comparison to the estimated 36 billion tons of CO2 released from fossil fuel combustion annually. Thus, while human respiration contributes to the carbon cycle, it is dwarfed by industrial emissions regarded as the chief culprits of climate change.

Turning our attention to the topic of flatulence, we encounter a fascinating component of human digestion. Human farts primarily consist of nitrogen, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and methane, with methane being the most potent greenhouse gas among them. Methane can trap heat in the atmosphere many times more effectively than CO2, making it a significant contributor to global warming. Surprisingly, research suggests that the average person may produce about 0.5 to 1 liter of gas per day, resulting in negligible methane emissions on an individual scale.

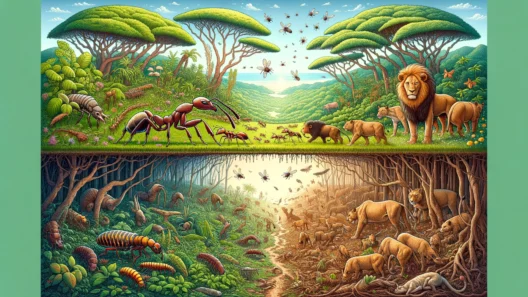

To further assess the implications of human emissions, we must explore the larger context of agriculture, where animal digestion plays a consequential role. Livestock, particularly cattle, produce substantial methane through enteric fermentation— a process inherent to their digestive systems. Estimates indicate that a single cow can emit up to 220 pounds (approximately 100 kilograms) of methane annually, highlighting the stark difference between human emissions and those from livestock. Consequently, the issue of methane emissions becomes more pronounced when examining agricultural practices rather than human flatulence directly.

The reality is that human farts and the act of breathing, while comprising parts of the global carbon cycle, make an almost negligible contribution to global warming when contrasted with larger systemic factors such as industrial pollution and agricultural emissions. This perspective highlights a fundamental principle: individual actions can be influential, but systemic change is where the real impact lies.

Moreover, scientific literacy plays a crucial role in dissolving misconceptions surrounding greenhouse gas emissions. The popular meme likening human flatulence to a significant cause of climate change serves to underscore a profound misunderstanding. Many individuals, eager to attribute every aspect of their existence to climate change, overlook the broader, far more impactful activities that contribute to global warming. Our fascination with such quirky notions distracts from engaging with critical environmental challenges, one of which is the urgency of reducing industrial emissions and promoting sustainable practices.

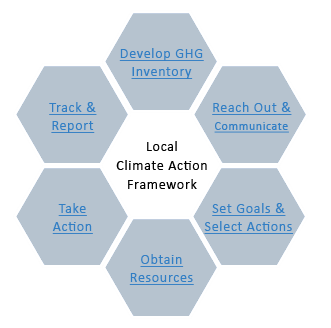

Another vital consideration in this discourse is the effectiveness of carbon offsetting measures. As discussions surrounding carbon neutrality proliferate, some may ponder whether offsetting methane emissions from livestock could also extend to human emissions, including those from respiration and digestion. However, given the minuscule contribution of human bodily functions to the overall greenhouse gas flux, the efficacy of such measures remains dubious. Rather than diverting attention to individual bodily functions, efforts ought to concentrate on systemic changes in transportation, energy consumption, and land-use practices.

As we dissect the nuances of this issue, it is essential to harness enthusiasm for environmental stewardship. Instead of being caught up in discussions centered around the inconsequential emissions of human biological functions, individuals can focus on adopting practices that engender meaningful change. Facilitating public awareness campaigns about sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, and efficient waste management can yield significant environmental benefits. Such strategies not only address pressing climate concerns but also instill a sense of responsibility in communities.

In conclusion, while it is amusing to consider whether human farts and breathing contribute to global warming, the factual evidence suggests that they do not significantly impact climate change. The bewildering inquiries surrounding human emissions serve as a reminder of our collective curiosity but should also urge us to concentrate our efforts on addressing mainstream sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The path to mitigating global warming lies in enhancing our understanding of environmental systems and fostering a shift toward sustainable practices. In the battle against climate change, it is imperative that we empower ourselves and others with facts and actionable strategies for collective progress.