The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect has become increasingly prominent in discussions surrounding climate change, especially for urban areas. This phenomenon, where metropolitan regions experience significantly warmer temperatures than their rural counterparts, raises vital questions about data interpretation and the implications for global climate trends. As urbanization continues to burgeon, the question must be asked: Is the Urban Heat Island Effect skewing climate trends? This inquiry touches on environmental science, urban planning, socioeconomic considerations, and the broader implications for understanding our planet’s shifts in climate.

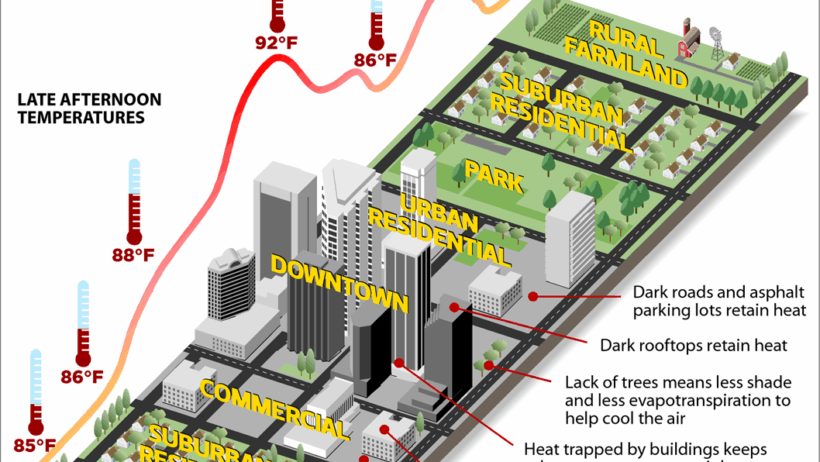

The UHI effect is rooted in the physiological characteristics of urban landscapes. Cities, with their concrete structures, asphalt pavements, and infrastructure, absorb and retain heat more effectively than natural landscapes. The materials employed in urban construction—stone, metal, and glass—tend to have a higher thermal conductivity compared to rural vegetation and soils. As a result, these urban surfaces not only heat up faster but also cool down more slowly than their rural counterparts. This creates a significant temperature differential that is particularly pronounced during the day and in the summer months, leading to an entirely different microclimate within city boundaries.

One critical aspect of the UHI effect is its temporal variability. Urban areas tend to show higher temperatures, particularly at night. Researchers have observed that while daytime temperatures may reflect broader climatic conditions, nighttime temperatures can deviate considerably due to heat retention in urban environments. This creates a skewed perception of climate trends if urban data is treated similarly to rural data. Consequently, the average temperature increase reported might dramatically misrepresent the overall climatic changes at a macro level.

At the heart of this phenomenon lies the conundrum of data collection and interpretation. Standard global temperature datasets often amalgamate urban and rural temperature readings, which can obscure the true nature of climate change. As cities constitute a mere fraction of the Earth’s surface area, their localized heat patterns can disproportionately influence average temperature calculations. This amalgamation can lead to an overestimation of warming trends in regions where urbanization has been rapid, thus masking the more holistic and potentially nuanced issues surrounding climate change in less developed areas.

Moreover, the UHI effect exacerbates challenges associated with climate adaptation and mitigation strategies. Policymakers addressing climate issues may inadvertently focus on urban areas based solely on skewed temperature data, potentially neglecting rural areas that may be experiencing different, and often severe, climatic fluctuations. Fighting climate change necessitates a comprehensive understanding of temperature dynamics across diverse landscapes, rather than a focus constrained by urban-centric data interpretations.

Another layer of complexity regarding the UHI effect is its interaction with socioeconomic disparities. Urban heat islands often exacerbate the vulnerability of marginalized communities. Low-income neighborhoods frequently lack adequate green spaces or reflective surfaces, which could mitigate heat. The intensity of the UHI effect thus disproportionately impacts those who are already at a disadvantage, leading to health risks such as heat stress and respiratory problems. As temperatures rise and the UHI effect intensifies, the implications of climate change deepen for these communities, revealing a stark intersection between environmental justice and urban planning.

Furthermore, urban planning strategies can play a critical role in mitigating the UHI effect. Green roofs, increased vegetation, and reflective building materials can significantly reduce localized temperature extremes. Some cities have begun to implement comprehensive urban forestry strategies aimed at cooling urban areas while enhancing biodiversity and improving air quality. However, these initiatives require substantial investments and long-term commitments, and they must be informed by empirical climate data that accurately reflects geographical variances. Without negating the existence of the UHI effect, efforts must explore its mitigative approaches and broader implications for urban sustainability.

This brings us to the broader implications for climate modeling and environmental projections. The UHI effect requires nuanced consideration in climate models that predict future trends. Climate scientists must delineate rural and urban data to achieve a granular understanding of temperature changes. A failure to account for the UHI effect may result in misleading climate models that overlook critical environmental feedback mechanisms.

In conclusion, the Urban Heat Island effect undoubtedly skews climate trends, presenting a multifaceted dilemma that intertwines urban geography, social equity, and effective policy formation. Urban areas, through their unique characteristics and challenges, illustrate the urgent need for comprehensive climate assessment methods that differentiate between urban and rural dynamics. As awareness of the UHI effect grows, it becomes imperative for stakeholders, including urban planners and climate policymakers, to integrate this understanding into their frameworks. Addressing the UHI effect not only fosters a deeper comprehension of climate change but also ensures a path toward resilience that is equitable for all communities.