Climate change has increasingly become a focal point of discussion, particularly the critical threshold of a 1.5°C rise in global temperatures above pre-industrial levels. As global average temperatures inch closer to this limit, an array of complex implications unfolds. The dire consequences of surpassing this threshold resonate through ecosystems, weather patterns, and human societies. It raises an urgent question: have we irreversibly hit the 1.5°C limit, and what does that entail?

Firstly, establishing whether we have indeed crossed the 1.5°C threshold necessitates a clear understanding of the temperature measurement process. The baseline for measuring this increase is typically set at the late 19th century, around the years 1850-1900. Currently, climate data indicates that we are precariously close, with global average temperatures rising approximately 1.1°C to 1.2°C since this baseline. This increment is significant enough to provoke noticeable changes in the environment, but the pivotal question lies in our trajectory. As carbon emissions continue to climb, it becomes imperative to analyze not just the current situation but also projections for the future.

The fascination with the 1.5°C limit, particularly within the scientific community, stems from its designation in the Paris Agreement, where nations globally committed to limiting temperature rise to avoid catastrophic climate disruptions. This benchmark signifies more than just a number; it represents a tipping point where the risk of severe impacts on natural and human systems dramatically escalates. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) asserts that if temperatures exceed this limit, we could witness extensive biodiversity loss, increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events, and destabilizing sea-level rise.

Moreover, the consensus among scientists indicates that reaching or exceeding the 1.5°C threshold would exacerbate existing social inequalities and vulnerabilities. Vulnerable populations, particularly in the Global South, are disproportionately affected by climate change, facing food insecurity, displacement, and deteriorating health conditions. Thus, the implications of crossing this boundary stretch beyond environmental concerns, entangling various socio-economic factors.

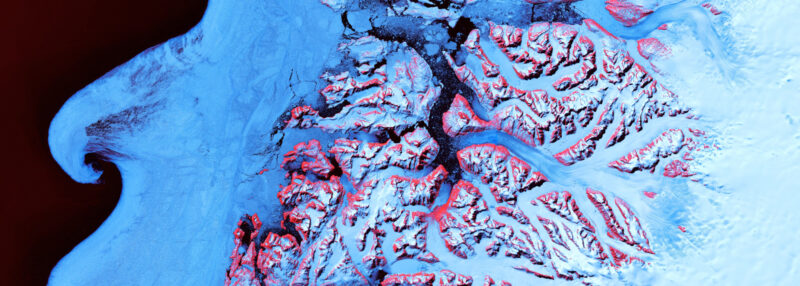

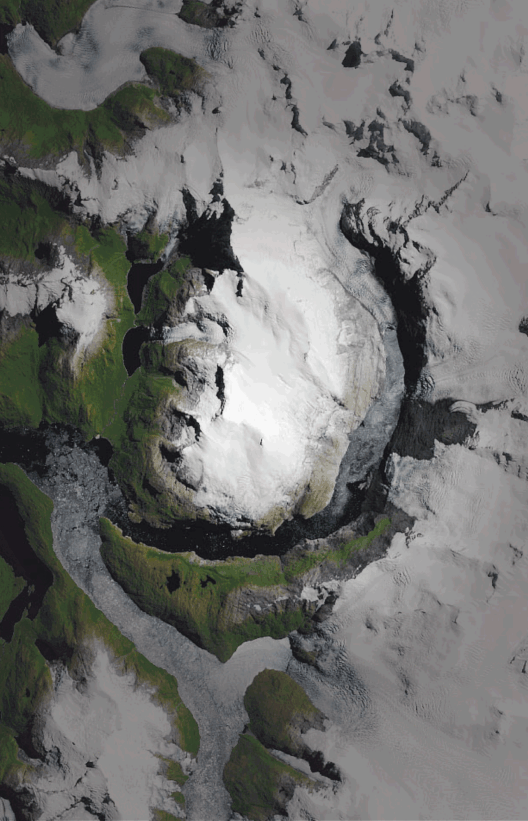

The tantalizing yet alarming notion of having already hit or being on the brink of surpassing the limit arises from specific environmental signals. For instance, unprecedented heatwaves, unusual precipitation patterns, and retreating glaciers contribute evidence to this fascination. The Arctic region has witnessed unparalleled temperature rises, leading to rapid ice melt, which not only impacts global sea levels but also influences weather patterns around the world. Such climatic anomalies provoke a frenzied debate regarding their attribution to anthropogenic activities versus natural variances.

Perhaps another layer of this discussion involves the psychological and cultural dimensions surrounding climate change. The concept of a “limit” can evoke a sense of urgency akin to a countdown – a race against time. This urgency is palpable in policy discourse, with activists and policymakers alike advocating for accelerated decarbonization pathways. The “1.5°C” becomes a rallying cry, embodying hope and action against an otherwise grim scenario. However, it can simultaneously lead to despondency and inaction among populations who feel the burden is too great to shoulder.

In science and research, the 1.5°C limit incites a diverse array of responses. Climate scientists have been rigorously modeling potential pathways to mitigate temperature rises, investigating scenarios that hold promise for limiting global warming. These modeling efforts consider factors such as carbon capture technology, renewable energy innovations, and changes in land use practices. However, they underscore the notion that achieving this target necessitates unprecedented changes in human lifestyle and consumption patterns.

The urgency to adhere to the 1.5°C threshold is exacerbated by feedback loops inherent in the climate system. As polar ice melts, less sunlight is reflected back into space, leading to further warming. Similarly, thawing permafrost releases methane – a potent greenhouse gas – into the atmosphere. These feedback mechanisms illustrate the complex interrelatedness of environmental systems, highlighting the risks of humanity’s continued inaction.

Addressing the consequences of surpassing the 1.5°C limit requires a multi-faceted response. Transitioning to a low-carbon economy entails rethinking energy sources, enhancing energy efficiency, and investing in sustainable infrastructure. Politically, it necessitates global cooperation and commitment, thus reaffirming the significance of international agreements like the Paris Accord. Local initiatives that promote sustainable practices, conservation, and resilience are equally vital in combating the nuanced challenges that surpassing the 1.5°C threshold would present.

In conclusion, while we have not conclusively hit the 1.5°C limit, the imperceptible nature of temperature rise creates an indelible sense of urgency. Understanding the implications of this threshold serves not merely as an academic exercise but as a required framework for action. As societies grapple with the reality of climate change, the depth of our responses must match the gravity of the challenges. The looming possibility of exceeding the 1.5°C threshold necessitates collective action and profound shifts in policy, technology, and cultural attitudes towards our environment. In moving forward, the pivotal focus must remain on climate mitigation strategies that can steer us away from hitting this critical limit and safeguard our planet for future generations.