The interplay between human-made substances and the natural environment is a complex arena, fraught with implications that extend to the very fabric of our climate. Among the most insidious environmental offenders are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), hydrofluorocarbons (HCFCs), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs)—synthetic compounds pivotal in refrigeration, air conditioning, and aerosol propellants. While their role in depleting the ozone layer has garnered attention, an equally concerning aspect is their contribution to global warming. To unpack this issue, we must delve deep into the mechanisms of these chemicals and their far-reaching repercussions on our planet.

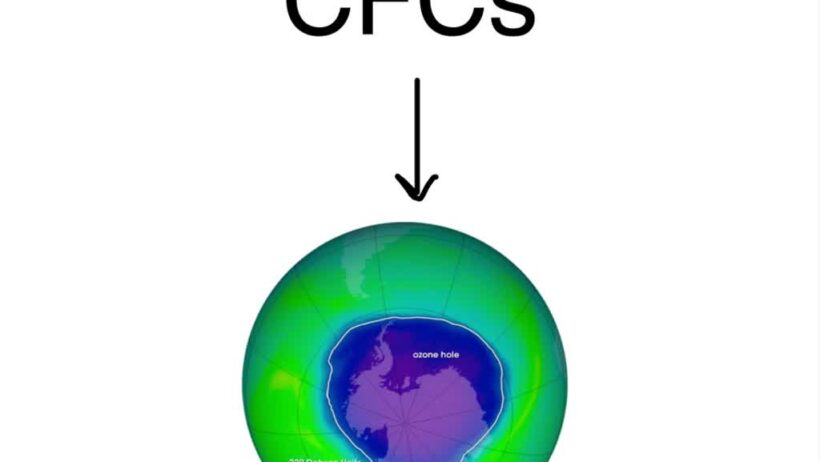

CFCs were heralded as a revolutionary class of compounds introduced in the 1920s, primarily due to their stability and non-flammability. They quickly became the standard for refrigerants and aerosol propellants, with perceptions of safety and efficacy overshadowing their ecological impacts. However, it was not long before scientific investigations revealed their propensity to migrate into the atmosphere, eventually reaching the stratosphere. There, UV radiation catalyzes their decomposition, liberating chlorine atoms that wreak havoc on ozone molecules—a critical layer of the Earth’s atmosphere that serves as a shield against harmful solar radiation.

The destruction of the ozone layer is, of course, a significant concern, but equally alarming is the role of CFCs and HCFCs in exacerbating climate change. These compounds possess formidable global warming potentials (GWPs); in many instances, they are thousands of times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide (CO2). Understanding this heat-trapping capability is crucial in framing the broader narrative of anthropogenic climate change. The potency of CFCs as greenhouse gases drives home the urgency for stringent regulations on their production and use.

Once released, CFCs remain in the atmosphere for extended periods, typically ranging from 50 to 100 years. This longevity allows for a cumulative warming effect, intensifying their impact on climate systems over time. To illustrate, consider the cognitive dissonance that arises from the use of CFCs in cooling systems: while they provide immediate relief in the form of stabilized indoor temperatures, their latent warming potential orchestrates a significant lag in global temperature increases. With this knowledge, it becomes clear that our comfort comes at the expense of long-term planetary health.

The introduction of HCFCs was initially considered a step in the right direction, as these compounds were designed to be less harmful to the ozone layer compared to their CFC predecessors. However, the irony is palpable; although they have a lower ozone depletion potential, HCFCs are still potent greenhouse gases. In fact, many HCFCs also harbor GWPs in the hundreds, contributing to climate change while perpetuating the notion of a safer alternative. As nations pivoted away from CFCs and applauded HCFCs as better choices, they inadvertently maintained reliance on harmful substances, thus prolonging the climate crisis.

As a response to the damaging impacts of CFCs and HCFCs, the Montreal Protocol was enacted in 1987—a watershed moment in environmental governance aimed at phasing out substances responsible for ozone depletion. This landmark treaty demonstrated the power of collective action and international cooperation. However, the focus on ozone depletion often eclipsed the greenhouse gas implications of these substances. Even as the protocol successfully curbed CFC use, the environmental community must champion a more holistic approach that includes the mitigation of their warming effects.

Transitioning to HFCs was seen as a more climate-friendly alternative; their formulations aimed to eliminate the chlorine-related ozone depletion. However, this transition was riddled with complications. While HFCs do not pose a direct threat to the ozone layer, they remain potent greenhouse gases, with millions of tons still being released into the atmosphere annually. Recent estimates suggest that the collective impact of HFCs could contribute to a rise in global temperatures by as much as 0.5°C by the end of the century. To mitigate this, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol was adopted in 2016, setting forth a global commitment to phase down HFCs and usher in technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Exploring the alternatives to CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs reveals promising avenues for mitigating their climate ramifications. Natural refrigerants—such as ammonia, carbon dioxide, and hydrocarbons—offer environmentally benign alternatives. These natural substances not only have minimal GWPs but also exhibit negligible ozone depletion potential, establishing a path toward sustainability. The challenge lies in transitioning industrial practices and consumer behaviors toward these alternative solutions while simultaneously amplifying awareness of synthetic refrigerants’ environmental impact.

Additionally, comprehensive public policy reform is paramount. Governments worldwide must enact rigorous emissions standards, incentivize the adoption of green technologies, and foster public awareness regarding the consequences of their choices. Education plays a foundational role in facilitating an informed citizenry; when individuals understand the ripple effect of everyday actions—such as using aerosols or neglecting refrigeration units—they become empowered to opt for alternatives.

In summation, the detrimental effects of CFCs, HCFCs, and HFCs extend beyond their contributions to ozone layer depletion. Their roles as potent greenhouse gases render them significant contributors to global warming, necessitating urgent policy action and public engagement. By confronting the reality of these substances and ushering in innovative alternatives, society stands at a pivotal crossroads—a chance to shift the trajectory of climate change and safeguard the planet for future generations. The time to act is now. Understanding and addressing the interconnectedness of these substances with climate change is not just beneficial; it is imperative for a sustainable future.