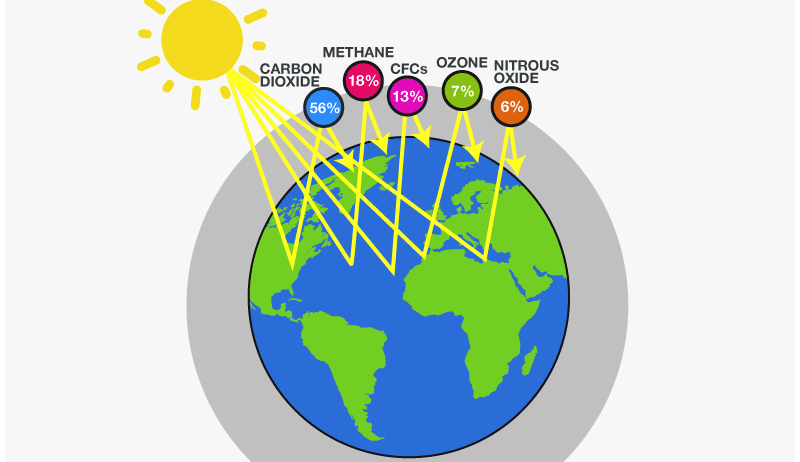

The hypothesis linking carbon dioxide (CO₂) concentrations in the atmosphere to global warming has been a cornerstone of climate science and policy-making. This relationship is rooted in the greenhouse effect, wherein certain gases in the Earth’s atmosphere trap heat, preventing it from escaping into space. While this concept is widely accepted and underscored in many scientific studies, it is prudent to undertake a critical reassessment of the CO₂-global warming hypothesis. This involves examining not only the empirical evidence supporting the hypothesis but also exploring the multifaceted dynamics and complexities that often underpin climate phenomena.

At the outset, the prevailing narrative holds that increased levels of CO₂ resulting from anthropogenic activities—such as fossil fuel combustion, deforestation, and industrial processes—correlate with rising global temperatures. Detailed analyses show a marked increase in CO₂ concentrations since the Industrial Revolution, with significant implications for global climate. The Keeling Curve, which illustrates the rise in atmospheric CO₂ since the late 1950s, serves as a stark testament to this trend. However, correlation does not imply causation, and this critical distinction must be acknowledged.

A common observation in climate science is the lag between increases in CO₂ concentrations and subsequent temperature rises. Paleoclimate data, derived from ice cores and sediment layers, reveal that temperature changes often precede fluctuations in CO₂ levels. This temporal disconnect raises intriguing questions regarding the mechanisms at play in Earth’s climate system. It suggests that while CO₂ is a potent greenhouse gas, other factors may also exert significant influence over temperature dynamics.

To delve deeper, one must consider the role of solar irradiance in influencing climate. Solar output varies over time due to natural cycles, which in turn affects the Earth’s climate. The Milankovitch cycles, for example, describe the long-term variations in the Earth’s orbit and axial tilt, leading to periods of glacial and interglacial climates. Understanding these natural processes is essential because they can modulate the climate system independently of CO₂ levels. Such insights highlight the complexity of climate interactions and challenge the oversimplified narrative that solely attributes climate change to human activities.

Another critical component of this reassessment is the feedback mechanisms within the climate system. Positive feedback loops, such as the melting of polar ice, contribute to further warming by decreasing the Earth’s albedo—its ability to reflect sunlight. Conversely, negative feedback mechanisms, like increased cloud cover, can mitigate warming. The interplay of these feedbacks can obscure the clear attribution of temperature changes to increased CO₂ alone. It is essential to acknowledge that the climate system is an intricate web of interactions where multiple variables collaborate, sometimes in unexpected manners.

In scientific discourse, it is vital to examine alternative hypotheses that could account for observed climate changes. The concept of climate sensitivity—the degree to which temperature responds to increased CO₂—is subject to considerable debate. Various studies have proposed different values for climate sensitivity, with implications for predicted temperature increases. Higher sensitivity estimates suggest catastrophic warming, while lower estimates indicate more moderate changes. The consequences of these varying stances on climate policy are profound, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of climate projections.

Moreover, the potential for adaptation and resilience in natural ecosystems and human communities raises further questions. While predictions regarding extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and habitat loss are alarming, many species and communities are already adapting to shifting conditions. Innovations in technology and sustainable practices provide avenues to mitigate the impacts of climate change, suggesting that while the threat of warming is significant, human ingenuity can play a role in addressing the challenges posed by climate variability.

Critics of the CO₂-global warming hypothesis often point to historical periods of climate stability and instability that occurred without major fluctuations in CO₂ levels. The Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age serve as examples where natural variability shaped climate outcomes in ways that are not fully explained by greenhouse gas concentrations. These historical antecedents compel a reexamination of how much weight should be assigned to CO₂ as the primary driver of contemporary climate change.

The socio-political dimensions surrounding the climate discourse cannot be overlooked. An effective approach to climate action requires transparent communication and collaboration across diverse stakeholders, including governments, industries, and communities. It’s essential to foster an environment where scientific inquiry is encouraged, and diverse perspectives are considered. This is pivotal in avoiding the pitfalls of dogmatism that can skew the perceived urgency of addressing climate change. Such an inclusive dialogue can pave the way for innovative solutions and collective action.

In conclusion, while the hypothesis linking CO₂ to global warming has substantial empirical backing, a critical reassessment reveals a labyrinth of complexities and uncertainties that merit thorough exploration. The interplay of various natural and anthropogenic factors, feedback dynamics, alternative hypotheses, and adaptive capacities all contribute to a richer understanding of climate change. It is apparent that a simplistic view focusing solely on CO₂ emissions may undermine our ability to devise effective strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate impacts. Thus, a holistic approach to climate science, one that embraces multipolarity in driving factors and promotes vigorous investigation, is essential for safeguarding the future of our planet.