The discourse surrounding climate change has evolved considerably over recent decades. As the impact of global warming becomes increasingly evident, scientists and the general public alike are grappling with the complexities of this critical issue. A rather intriguing question emerges from this discussion: Are scientists truly changing their minds about global warming? With an avalanche of data corroborating anthropogenic influences on climate, one might assume that consensus is absolute. However, the landscape is more nuanced than it appears.

First, it’s essential to establish what is meant by “changing minds.” Science is inherently a dynamic process. Researchers frequently refine their theories in light of new evidence, and the consensus itself can occasionally shift as new paradigms emerge. The progression of scientific understanding is not merely a linear trajectory but one characterized by oscillation, debate, and reassessment.

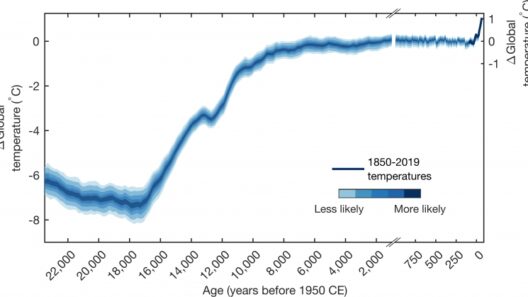

One noteworthy area where scientists have had to reassess their positions is the pace and scale of climate change. Earlier models predicted gradual increases in temperature and sea level. However, more recent studies indicate that the effects of climate change are manifesting at an alarming rate. The acceleration of glacial melt, unprecedented heatwaves, and rising ocean temperatures compel scientists to reevaluate the implications of their prior forecasts. Herein lies a potential conundrum: Are older models, which underestimated these phenomena, now leading to a belief that climate scientists may have been overly cautious?

This leads us to an essential aspect of scientific inquiry: peer review and discourse. The field of climate science is rife with intense debates, and differing opinions often emerge in scholarly circles. Some scientists vocally argue against the urgency of climate action, citing natural climate variability. These dissenting perspectives can create an illusion that the scientific community is divided. However, upon closer inspection, the scientific consensus remains robust; a significant majority acknowledges human-induced climate change as a pressing crisis. Yet, the variability in viewpoints also beckons the question: Are scientists effectively communicating the urgency of their findings to the public and policymakers?

Moreover, the challenge of public perception cannot be ignored. In a world inundated with information, climate science sometimes competes with misinformation and skepticism. Public beliefs about climate change often lag behind scientific understanding, influenced by political ideologies, socioeconomic factors, and geographical location. This disjunction can lead to an apparent disparity between scientific consensus and public opinion. One might ponder whether scientists should recalibrate their outreach strategies to bridge this gap. Should they adopt more accessible languages or engage in novel communication methods to garner greater public support?

In light of these challenges, it’s also pertinent to explore how adaptation and mitigation strategies are evolving. The notion that scientists are “changing their minds” might not solely refer to beliefs about climate change itself, but rather to the evolving methodology by which societies tackle its consequences. The advent of innovative technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, showcases an evolution in thinking. Here, scientists are moving from mere prediction and analysis to proactive solution-oriented strategies. The challenge, then, is whether these advancements will be adopted widely enough to effect tangible change.

Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration is becoming increasingly pivotal. The intersection of social sciences, economics, and environmental advocacy has opened the floor for refreshing dialogues and ideas. When scientists enlist the expertise of economists and sociologists, they can garner insight into how best to enact change. Such collaborations point to a transformative mindset; this is not about changing one’s stance on climate change but rather about expanding one’s breadth of understanding to foster impactful action. Is it safe to propose that in doing so, the scientific community is indeed altering its approach, if not its core beliefs?

Another facet warrants discussion: the role of emerging evidence in shaping scientific opinion. The continuous stream of data concerning climate patterns, extreme weather events, and ecosystem disruptions has inevitable ramifications. Each groundbreaking study holds the potential to reshape scientific consensus, necessitating that researchers remain adaptable. Such adaptability is not a sign of indecision but rather a hallmark of scientific integrity. Are scientists, by remaining open to new information, savagely protective of their foundational beliefs, or are they showing a sophisticated understanding of the fluidity of knowledge?

In conclusion, the question “Are scientists changing their minds about global warming?” is multifaceted. While the core acknowledgment of anthropogenic climate change remains steadfast, nuances in understanding, communication, and strategy reflect an evolving narrative. The commitment to debate, the refinement of models, and interdisciplinary collaborations showcase a dynamic field that thrives on inquiry and innovation. As societal challenges mount, the urgency for decisive action escalates. The scientific community has not so much changed its mind but has rather broadened its scope of understanding, adapting to meet the exigencies of a warming world. As discussions continue, what remains paramount is the need for collective action, informed by evolving scientific insights, to secure a sustainable future for generations to come.