In the contemporary landscape of environmental discourse, the question of belief versus denial in the realm of climate science is both pertinent and provocative. With alarming data revealing that nearly 15% of Americans outright reject the validity of climate change, we are compelled to ponder: what constitutes a credible standpoint in the face of overwhelming scientific consensus? This inquiry not only opens the door to understanding public perception but also lays bare the complexities of human cognition and societal influences surrounding climate science.

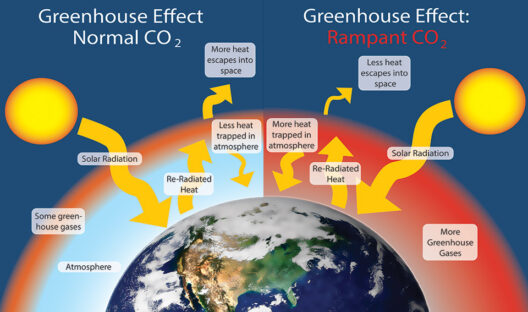

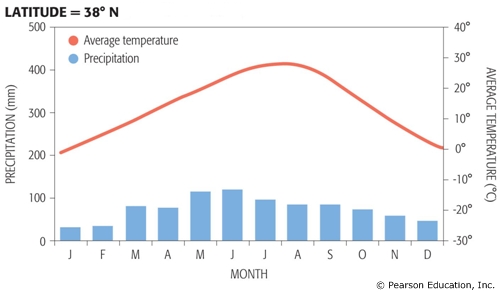

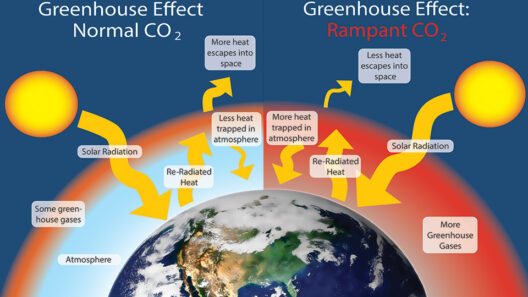

First and foremost, it is essential to delineate the foundations upon which climate science is built. Scientific consensus regarding climate change is not merely the product of isolated studies; it emerges from a vast and intricate web of interdisciplinary research. Over decades, thousands of peer-reviewed articles have converged on the understanding that climate change is a tangible phenomenon, primarily driven by anthropogenic factors such as greenhouse gas emissions from industrial activities, deforestation, and agricultural practices. The unequivocal conclusion drawn by the majority of scientists is that climate change poses an existential threat to ecosystems and human societies alike.

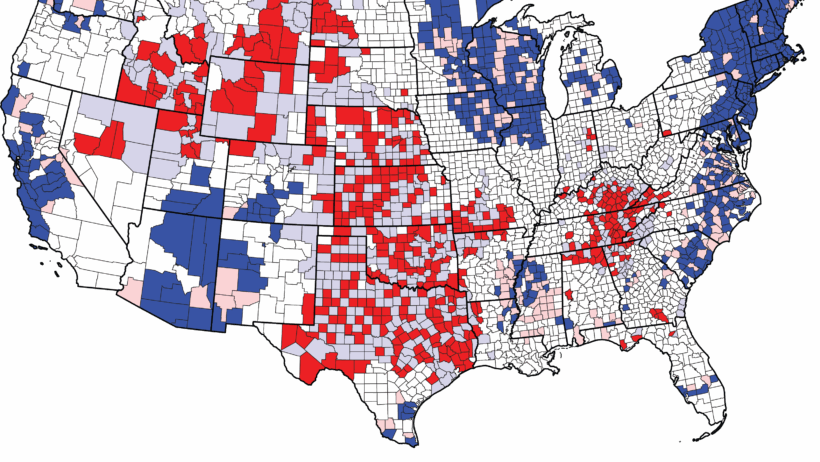

Yet, despite this scholarly consensus, an observable divide remains in the American populace. Factors contributing to this skepticism range from misinformation campaigns propagated by vested interests to political ideologies that resist acceptance of scientific data contrasting with one’s worldview. In this context, it can be illuminating to examine the sociocultural underpinnings that influence belief systems about climate change. How does an individual’s upbringing, education, and social milieu shape their acceptance or denial of scientific evidence?

In many cases, the interplay of identity and ideology is significant. For instance, individuals who identify with certain political factions may adopt environmental skepticism as part of a broader ideological toolkit. This phenomenon suggests that climate change beliefs can be intertwined with a person’s relational and group dynamics—essentially, aligning beliefs with those of one’s social network. As such, the rejection of climate science may serve as an act of solidarity with a particular group, rather than a reflection of empirical understanding.

Furthermore, the role of misinformation cannot be overstated. In the age of information, where social media dominates discourse, sensational claims and misleading narratives can permeate the public psyche swiftly. The proliferation of “alternative facts” regarding climate science poses a formidable challenge for proponents of environmental stewardship. Indeed, tackling misinformation is not merely about correcting falsehoods; it involves cultivating critical thinking skills and empowering individuals to engage with scientific materials constructively.

Educational initiatives aimed at fostering environmental literacy represent a pivotal strategy in combating disbelief. Curriculum reforms incorporating climate science can engender a nuanced understanding of environmental issues from a young age. Moreover, interdisciplinary approaches that weave together scientific, ethical, and economic dimensions of climate change can help individuals grasp the multifaceted nature of the challenge. Such educational endeavors can also nurture empathy toward the natural world and underline the interconnectedness of human existence and ecological integrity.

However, education alone may not be sufficient to bridge the chasm of disbelief. Emotional engagement is crucial in shaping public opinion and mobilizing action. Narratives that resonate on a personal level have the potential to inspire change. Storytelling, particularly involving local scenarios and the lived experiences of those affected by climate-related disasters, can humanize abstract data and statistics. By fostering empathy, these narratives have the power to shift perspectives and encourage a more profound recognition of the urgent need for climate action.

Let us also consider the economic implications of climate belief. The burgeoning green economy presents a dual opportunity: it promises job creation in sustainable industries while simultaneously addressing the ecological crisis. The transition towards renewable energy sources and sustainable practices can stimulate local economies, thus creating a vested interest in acknowledging climate change as a pivotal issue. Proponents of climate action can frame the conversation around economic resilience, underscoring that the denial of climate science may lead to missed opportunities for innovation and employment.

Nonetheless, challenges remain in the fight against denial. There are individuals and organizations that actively perpetuate skepticism and resistance to change. The perpetuation of a false dichotomy—casting climate science as controversial—creates a fertile ground for disbelief. The persistent portrayal of legitimate scientific debate as mere opinion undermines public trust in expert opinions. To counter this narrative, it is imperative to engage with skeptics respectfully, providing evidence and remaining steadfastly committed to transparent dialogue.

But herein lies a contemplative challenge: what if our efforts merely reinforce existing beliefs, leading to polarization rather than persuasion? The phenomenon known as the “backfire effect” illustrates that confronting people with contradictory evidence can sometimes entrench their original beliefs even further. Consequently, approaches emphasizing shared values and common goals—rather than divisive rhetoric—may yield more fruitful conversations about climate action.

In conclusion, navigating the treacherous waters of belief and denial in climate science necessitates a multifaceted, empathetic approach that engages with the psychological, sociological, and economic dimensions of the issue. While the statistics may paint a dismal picture, they also highlight the profound opportunity for dialogue, education, and sincere engagement. The question of how many Americans trust climate science is not merely a quantitative measurement; it is an invitation to explore deeper societal currents, challenge entrenched mindsets, and cultivate a collective resolve to deliver a sustainable future. The journey from skepticism to acceptance may be arduous, yet it is a path worth traversing for the health of our planet and generations to come.