Energy is a fundamental concept in both physics and our daily lives, influencing everything from how we power our homes to how we approach sustainability. To understand energy conservation during the process of work, we must first delineate what we mean by work in a physical sense. Work is defined in physics as the energy transferred when a force is applied to an object that moves in the direction of the applied force. The formula for work is simple: work (W) equals force (F) multiplied by distance (d), expressed visually as W = F × d. But how does this connect to our overarching question—can energy truly be conserved while work is being performed?

At first glance, it may seem counterintuitive. After all, performing work often requires the application of energy, whether it be lifting a weight, moving a vehicle, or spinning a turbine. However, the principle of conservation of energy states that energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only be transformed from one form to another. When work is done on an object, energy is transferred to that object, resulting in a change in its energy state.

To further dissect this, let’s consider kinetic and potential energy, the two most prevalent forms of mechanical energy. When you lift an object, you are converting kinetic energy from your muscles into potential energy of the object as it gains height. The potential energy (PE) of the object increases because of its elevated position, while your body expends energy through the performance of work.

So, can energy be “conserved” if work is being done? The answer lies in understanding energy transfers rather than energy losses. Throughout the act of doing work, energy is not disappearing; rather, it is being transformed or transferred. When you lift that heavy box, the work you do converts the chemical energy stored in your muscles into gravitational potential energy in the box. Therefore, while it may appear that energy is being ‘used up,’ it is only changing its form, embodying the core tenet of energy conservation.

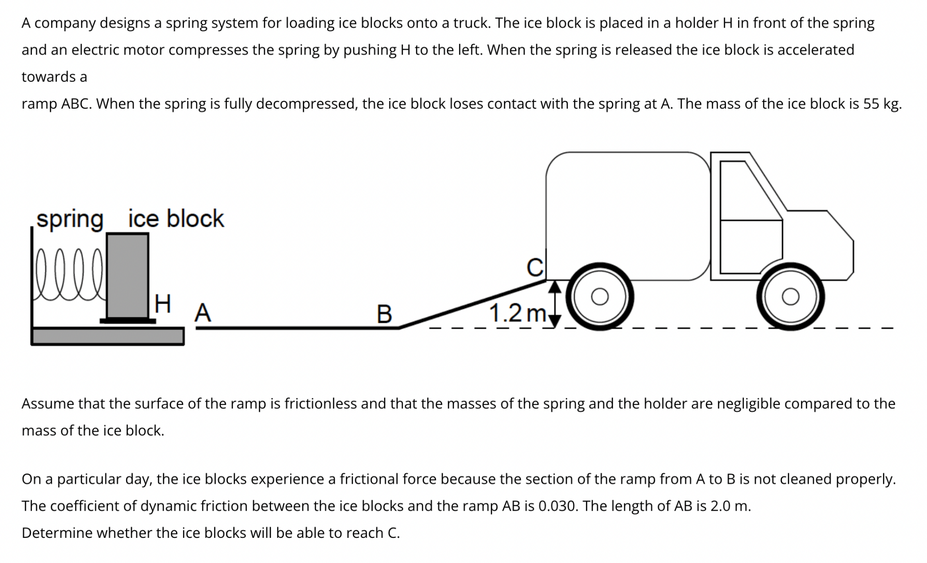

Another aspect to consider is the efficiency of energy conversion. Often, in practical scenarios, energy transforms aren’t 100% efficient. For instance, when machinery is used to lift objects, some energy is lost as heat due to friction. This inefficiency highlights the reality that while energy is conserved in a closed system, not all input energy is harnessed for useful work. It accentuates the importance of energy conservation techniques in engineering and design, instigating curiosity about how innovations could minimize energy loss in real-world applications.

In our exploration, we find ourselves at a crucial juncture—continuous work usually equates to ongoing energy flow. The very definition of work entails a transfer of energy, meaning that as long as forces are applied, energy is in motion. Each time you push, lift, or accelerate, energy is actively transformed, illustrating the dynamic nature of work and energy. The prospect of energy conservation thus becomes not a static state but an ongoing process filled with interactions between different forms of energy.

Yet, it merits attention to discuss various scenarios in which work does not conform to our traditional understanding of energy conservation. Take, for example, a pendulum swinging back and forth. As it reaches its highest point, the kinetic energy is momentarily paused while converted into potential energy. When it swings down again, the potential energy morphs back into kinetic energy. Although energy transitions appear seamless, outside forces—like air resistance—intervene, subtly siphoning off energy from the system. Thus, although energy is conserved within the ideal confines of the system, external factors can disrupt this equilibrium.

The stellar implications of these notions are vast, especially as we confront pressing environmental issues. Understanding how to effectively manage and conserve energy while work is being done offers pathways to improved efficiency and sustainability. It raises questions about how technology might evolve to harness wasted energy, a conundrum central to modern discourse on renewable and sustainable energy sources.

Envision a world in which the forces driving our daily activities—be it commuting to work or generating electricity—are not merely energy consumers but rather intricate systems of energy transfer where conservation is practiced instinctively. Concepts like regenerative braking in electric vehicles exemplify this principle, allowing kinetic energy usually wasted during breaking to be reclaimed and transformed back into usable energy. When we frame energy conservation through the lens of doing work rather than as an isolated entity, we ignite potential for innovation and increase public interest in sustainable practices.

As we round off this discussion, it becomes evident that the intricate ballet between work and energy conservation is not only a matter of physics but also a philosophy. The assertion that energy can be conserved while work is being done invites a paradigm shift in our understanding of energy management. The quest for greater efficiency, reduced waste, and innovative technologies prompts communities and industries alike to rethink how they utilize energy. By recognizing the transformative nature of energy, we cultivate curiosity and inspire action towards a more sustainable future.