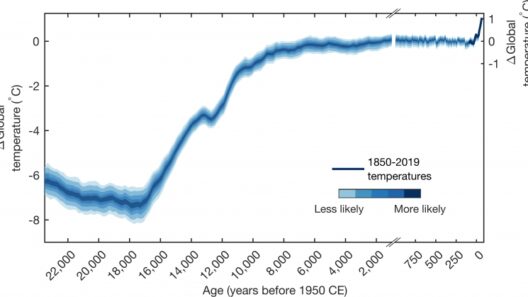

The phenomenon of climate change has spurred myriad responses, both from the scientific community and the public at large. One of the most intriguing, yet contentious, responses to this global crisis is the concept of geoengineering. This umbrella term encompasses a diverse array of large-scale interventions aimed at manipulating the Earth’s climate system to counteract anthropogenic climate change. Yet, as the allure of such technologies grows, so too does skepticism. Can geoengineering really save our planet?

To address this query, it is crucial to first understand the different types of geoengineering proposed. Broadly, geoengineering can be classified into two main categories: solar radiation management (SRM) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR). SRM techniques aim to reflect a small proportion of the Sun’s light and heat back into space, while CDR focuses on removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Techniques like stratospheric aerosol injection and marine cloud brightening fall under SRM, whereas afforestation, ocean fertilization, and direct air capture represent CDR methodologies.

The theoretical underpinnings of geoengineering resonate deeply with our existential anxiety concerning climate change. The increasing frequency of catastrophic weather events, rising sea levels, and drastic shifts in biodiversity are palpable reminders that urgent action against climate change is imperative. Geoengineering offers a tantalizing prospect: a potential technological panacea that might curb global warming, mitigate its effects, or even reverse damage already inflicted on ecosystems.

However, the allure of geoengineering is shrouded in ethical dilemmas and environmental concerns. Critics assert that reliance on such high-risk interventions could engender a dangerous complacency regarding more traditional efforts to combat climate change, such as reducing greenhouse gas emissions and promoting sustainable practices. This notion raises a pertinent question: Does the prospect of engineering our climate create a psychological buffer that allows society to justify inaction on the root causes of climate change? The answer may indeed lie in our reliance on technology itself.

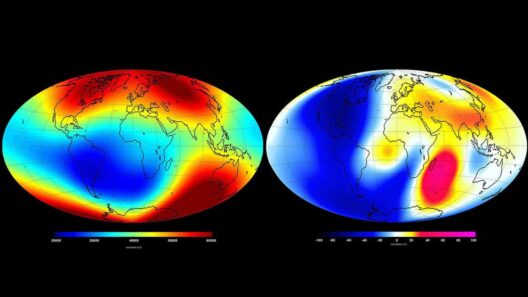

Furthermore, geoengineering introduces a multitude of unintended consequences. For instance, the deployment of stratospheric aerosols to reflect sunlight could potentially disrupt regional weather patterns, leading to droughts in some areas and inundation in others. The egalitarian principle of “one person’s solution is another’s problem” weighs heavily within the discourse surrounding geoengineering. Nations that are already vulnerable to the effects of climate change may bear the brunt of adverse side effects stemming from geoengineering implemented by more developed countries. The global implications underscore the need for thorough governance frameworks.

The scientific community remains divided on the feasibility and desirability of geoengineering solutions. Several studies highlight the significant technological, economic, and ethical hurdles still to be surmounted. Critics point out that the technologies required for effective geoengineering often remain in the experimentation phase and may not deliver anticipated outcomes. Additionally, the myriad uncertainties surrounding side effects necessitate rigorous assessment before any large-scale implementation can occur.

An intriguing aspect of geoengineering is its psychological impact; it captivates us with visions of human ingenuity triumphing over nature’s wrath. This fascination stems from a deep-seated belief in progress—an outlook that permeates modern society. Yet, it is this very notion that can obscure a sobering truth: humanity’s historical track record of managing ecosystems is fraught with failures. Examples abound, from the destruction of the Aral Sea to the introduction of non-native species leading to ecological upheaval. To assume that geoengineering will invariably succeed is to overlook history’s lessons.

As discussions around geoengineering unfold, they inevitably intersect with broader themes of justice and equity. Who gets to decide which geoengineering methods are employed? Whose voices are heard in the deliberative processes surrounding potential deployment? As countries confront the realities of climate impact, disparities in economic strength, technological access, and inherent vulnerabilities challenge us to consider who holds the reins in a geoengineered world. If geoengineering is to be considered as a viable tool, it must be framed within a context that prioritizes equity and inclusivity.

Moreover, the pursuit of geoengineering may inadvertently stymie investment in renewable energy technologies and other traditional mitigative measures which are crucial to combatting climate change. The over-reliance on technological fixes could divert essential resources away from sustainable practices like transitioning to solar, wind, and hydroelectric power. These approaches not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also foster community resilience and create jobs, making them a dual pathway toward healing our planet.

In conclusion, while geoengineering presents a thought-provoking array of possibilities for addressing climate change, the complexities surrounding its implementation cannot be understated. The prospects of unintended consequences, ethical considerations, and the potential to overshadow basic climate action mean that the road ahead must be navigated with caution and lucidity. Whether geoengineering can contribute meaningfully to climate remediation depends on our ability to balance these innovative tools with an unwavering commitment to reducing emissions and fostering sustainable practices. The time to act is now—without losing sight of our ultimate goal: a habitable planet for generations to come.