The discourse surrounding climate change has spawned a diversity of perspectives, often polarized around the concept of climate alarmism. On one side, we have those who emphasize the urgent threats posed by climate change, advocating for immediate action to avert catastrophic outcomes. On the other, critics argue that this alarmism might exacerbate economic struggles in the Third World. So, is climate alarmism impoverishing the Third World or saving it? This question necessitates a nuanced exploration of the intricate dynamics at play between environmental advocacy and socioeconomic realities.

To understand the implications of climate alarmism, it is crucial to define what is meant by the term. Climate alarmism encompasses the heightened rhetoric that posits existential threats resulting from climate change. Proponents assert that without immediate and radical interventions, we risk irreversible damage to our planetary ecosystem. In contrast, detractors argue that this zealous outlook could potentially undermine economic development efforts in vulnerable regions, particularly in the Global South.

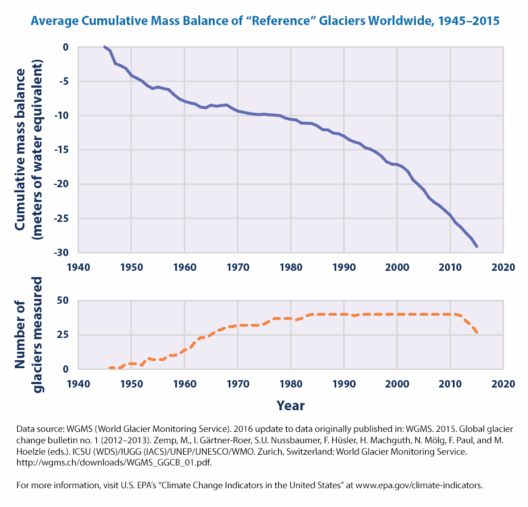

The Global South, often characterized by lower levels of industrialization and economic development, faces an inherent vulnerability to climate change. Countries in this region experience disproportionate effects from climate phenomena—ranging from crop failures to increased severity of natural disasters. This reality raises a critical question: does alarmist rhetoric galvanize aid and necessary reforms, or does it serve as a deterrent to investment and growth?

Supporters of climate alarmism contend that it is indispensable in garnering international attention and funding for climate adaptation and mitigation projects. When alarmism is mobilized effectively, it can precipitate significant funding and resources for developing nations. Remarkably, organizations like the Green Climate Fund have emerged to address precisely these imbalances by financing projects that reduce vulnerability to climate impacts. In this light, alarmism can be framed as a catalyst for momentum toward sustainable development.

Yet, the counterargument posits that the overwhelming focus on catastrophic scenarios can inadvertently lead to economic stagnation. When developing countries are regularly portrayed as the frontline victims of climate change, it can overshadow the potential for these nations to adopt green technologies and strategies that foster economic growth. The pervasive narrative of doom and gloom may deter foreign direct investment, as investors perceive heightened risks associated with climate-affected regions. Ironically, this may result in a self-fulfilling prophecy where alarmism not only backfires but also inhibits the very progress it seeks to promote.

The complexity of the situation is further compounded by the inequity in contributions to global emissions. Wealthier nations have historically borne the brunt of greenhouse gas emissions, whereas developing countries are often caught in a precarious position. They are not responsible for creating the climate crisis yet are frequently depicted as its primary sufferers. This discrepancy raises questions about moral responsibility and the efficacy of alarmism as a means to rectify longstanding inequalities within the international landscape.

Furthermore, developing nations often contend with the challenge of implementing climate initiatives within the context of existing socioeconomic issues. For instance, if a government prioritizes green technology but does so at the expense of essential services like healthcare or education, who benefits from this alarmist-driven agenda? The risk here is the potential for alarmism to misallocate resources that could otherwise aid in alleviating poverty. It begs the inquiry: should the focus be on immediate economic needs, or is there room for a holistic approach that marries development with sustainability?

One potential solution lies in collaborative frameworks that entail shared responsibilities and investment from countries across the spectrum of development. By fostering a dialogue that appreciates the distinct challenges faced by developing nations, alarmism can transition from a narrative of crisis to one of opportunity. Encouraging proactive measures—where nations invest in renewable energy sources and sustainable agriculture—could lead to burgeoning economies that are resilient in the face of climate abnormalities.

Moreover, the role of education cannot be overstated. Empowering communities through knowledge about sustainable practices and climate resilience can mitigate the adverse effects of climate change while driving local economies. Rather than succumbing to alarmism, communities can be equipped to innovate, adapt, and thrive in a changing environment. This consideration introduces the notion that perhaps saving the Third World requires a paradigm shift in how we engage with the themes of climate change.

In conclusion, the question of whether climate alarmism impoverishes the Third World or aids its survival is multifaceted. While alarmism has the potential to stimulate international funding and catalyze adaptation efforts, it can also hinder investment and perpetuate cycles of poverty. The imperative is to strike a balance—acknowledging the dire nature of climate change while simultaneously promoting development strategies that empower rather than impoverish. Only through informed, collaborative, and compassionate approaches can we truly address the complexities of climate change and its impact on the world’s most vulnerable populations.