In the lexicon of environmental discourse, the terms “climate” and “weather” often emerge as interchangeable, leading to profound misunderstandings about the Earth’s dynamic systems. However, the distinction between these two crucial concepts is not merely semantic; it embeds deeper implications for our understanding of global phenomena and our responses to them. Recognizing this difference can enhance discourse on climate change, enabling more informed decision-making at individual, societal, and governmental levels.

To appreciate the uniqueness of climate and weather, it is essential to elucidate each term’s definition. Weather refers to the short-term atmospheric conditions in a specific place at a specific time. It encompasses changes in temperature, humidity, precipitation, wind, and visibility. On the other hand, climate represents the long-term statistical average of weather patterns in a particular region over extended periods, typically 30 years or more. It includes an analysis of seasonal variations, long-term trends, and anomalies—enabling a comprehensive assessment of an area’s atmospheric behavior.

The allure of conflating climate with weather lies in the immediacy that weather conveys. A sudden downpour or an oppressive heatwave captures attention, prompting commentary and concern. Yet, such discussions often overlook the broader, more insidious trends shaping our planet. It is during extreme weather events that people may voice skepticism about climate change, citing localized anomalies as a counterargument against established scientific consensus. Notably, this perspective can be perilous, as it undermines crucial climate science that relies on data collected over substantial periods to illustrate notable shifts.

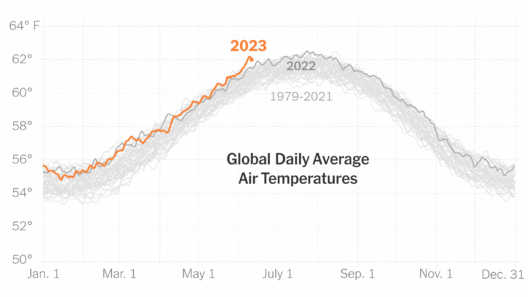

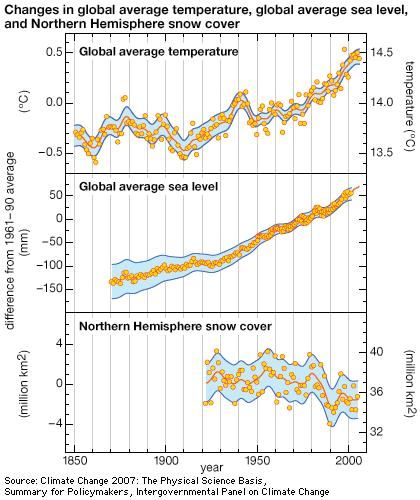

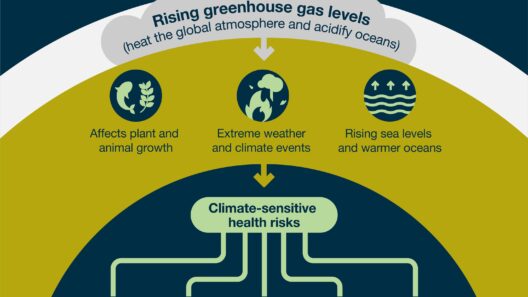

When a winter storm blankets a city, it does not negate the warming trend observed globally. Instead, it highlights the intricacies and variabilities of the climate system. This conflation also reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of how climate change operates. It is essential to recognize that climate change manifests not only through warmer average temperatures but also through increasingly erratic and severe weather patterns. Among the byproducts of climate change are altered storm intensities, drought frequency, and flooding risks. Each of these phenomena stems from longer-term climatic shifts rather than day-to-day weather variations.

To illustrate this difference further, consider the phenomenon of El Niño and La Niña. These climatic patterns significantly influence global weather events and demonstrate the interaction between climate and weather. El Niño is characterized by the warming of ocean surface temperatures in the central and eastern Pacific, which can result in far-reaching effects on weather patterns—from increased rainfall across the southern United States to drought conditions in Australia. Conversely, La Niña tends to bring cooler ocean waters, triggering opposite weather events. Understanding these oscillations requires a climate-centric viewpoint, as they manifest the ongoing fluctuations within our Earth’s climate system.

Furthermore, as we delve deeper into the implications of climate and weather, the sociopolitical dimensions emerge. The tendency to equate weather with climate can lead to misinformed policy decisions. Policymakers often fall prey to this conflation when attempting to justify or challenge climate action based on immediate weather occurrences. Such an approach risks advancing short-lived strategies that fail to address the long-term requirements for mitigating climate change. This phenomenon exemplifies the necessity for sustained public education that illustrates how individual weather events contribute to the overarching climate narrative.

The distinction between climate and weather also exposes the profound challenges environmental activism faces. Climate change is often perceived as a distant threat, abstract and detached from daily life. In contrast, weather invokes immediacy, as evident in local forecasts and seasonal patterns. Activists aiming to galvanize collective action must translate complex climate data and concepts into relatable narratives that people can understand. This requires an understanding of human psychology: the emotional response people exhibit towards immediate weather events is often much stronger than their reaction to gradual climatic changes.

A crucial responsibility for educators and communicators involves fostering an understanding of scale. While weather can change rapidly within hours or days, climate unfolds over the decades and centuries. This temporal disparity can create frustration, leaving individuals grappling with a lack of immediate agency regarding climate issues. Thus, a balanced approach must be employed—one that highlights both immediate weather events and their long-term implications within the context of climate change, creating a coherent narrative that facilitates understanding and action.

Moreover, as the scientific community continues to unravel the intricacies of our changing climate, it reveals an unsettling truth: climate change is not a solitary phenomenon; it is intricately woven into the fabric of our ecosystems, economics, and social structures. By clarifying the distinction between climate and weather, we can better articulate the urgency of climate action and the fundamental changes required to avert catastrophic outcomes.

In summary, the interplay between climate and weather is critical to understanding the challenges we face in addressing climate change. The words we choose to articulate these concepts bear significance, influencing public perception and policy. A robust dialogue built on a firm understanding of their distinctions is imperative to cultivating an informed audience capable of recognizing the implications of their actions on both a local and global scale. As we navigate the complexities of climate science and weather phenomena, our objective must remain clear: to ensure that our discussions align with scientific accuracy, illuminating the path toward a sustainable future.