The current climate crisis has sparked a myriad of debates among scientists, policy-makers, and the general public. One of the most pressing inquiries is whether today’s climate challenges surpass those of historic warmings. Is this indeed the worst crisis humanity has encountered? While the question may be playful, the implications are profoundly serious. To address this inquiry, we must delve into the mechanisms of climate change, its historical context, and the cascading effects of current warming trends.

Throughout Earth’s history, the planet has undergone significant climatic shifts, often characterized by dramatic temperature variations. Ancient epochs, such as the Pleistocene and the Holocene, were marked by alternating glacial and interglacial periods. The most notable instances include the Medieval Warm Period (MWP) from about 950 to 1250 CE and the Little Ice Age (LIA) that followed. While these historic events were indeed impactful, their causes and consequences differed markedly from the climate dynamics we observe today.

During the MWP, humanity experienced a relatively mild climate that facilitated agricultural expansion and population growth in Northern Europe. However, this warm phase was a regional anomaly rather than a global phenomenon, limited in its effects and not driven by anthropogenic influences. In contrast, the current trajectory of climate change is unprecedented in its rapidity and its direct linkage to human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels that emit greenhouse gases (GHGs).

Today’s warming, often referred to as anthropogenic global warming, is steeped in an alarming acceleration of global temperatures. Since the Industrial Revolution, the Earth’s average temperature has risen by approximately 1.2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. This current rate of change outstrips nearly all of the warming rates observed in historical climates, leading many scientists and environmentalists to contend that we are indeed witnessing an unparalleled crisis.

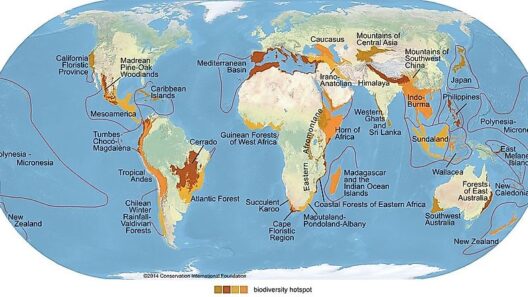

Another dimension to consider is the comprehensive pace at which climatic changes are affecting natural ecosystems and human societies alike. The correlation between rising temperatures and the frequency of extreme weather events is critical. We are currently observing an increase in the incidence of hurricanes, droughts, floods, and wildfires, exacerbated by the warmer atmospheres holding more moisture. In contrast, historic warm periods did not exhibit such a direct and widespread impact attributable to human influence.

In the realm of agriculture, the ramifications of today’s climate crisis are stark. The threat to food security looms large as shifting climatic zones and altered precipitation patterns jeopardize traditional farming regions. Historic warming episodes typically did not precipitate this level of risk. The relationship between climate and agriculture has always been intricate, but the scientific consensus now indicates that current changes are likely to render entire regions unsuitable for agricultural practices within decades.

Moreover, the socio-economic disparities exacerbated by climate change pose an additional layer of complexity. Vulnerable populations in developing nations are disproportionately affected, often lacking the resources and infrastructure to adapt to extreme weather events. This challenge harkens back to previous climatic shifts; however, the scale and interconnectedness of global society today compound the repercussions. The cascading effects of climate-related disasters can reverberate across borders in ways that historical events simply did not.

Yet, as we examine these challenges through a historical lens, we recognize an inherent resilience within humanity. Past societies have adapted to climatic changes, albeit with varying degrees of success. It is crucial to acknowledge that historical events also ignited innovation, prompting the development of new agricultural techniques, sustainable practices, and social systems. Applying these lessons from history invites a reflection on our current capabilities to not just endure, but to thrive amid adversity.

This brings us to a pivotal question: can today’s society harness the lessons learned from previous warming periods to combat the rapid climate changes we face? The historical context offers guidance, yet the distinguishing factor remains the sheer scale of our current predicament. The convergence of human impact and the rate of change introduces a new variable, one that renders complacency a luxury we can no longer afford.

As discussions unfold, the urgency for action intensifies. Public awareness campaigns, grassroots mobilizations, and international treaties exemplify a collective response that we must maintain and amplify. Historical climates did not spawn such mobilizations; rather, they were ultimately shaped by the ecological realities of their time. Each age had its challenges, yet our interconnected world demands a synergistic approach to problem-solving that transcends geography.

In summation, while posing the question “Is this the worst climate crisis?” invites contemplation of our historical climate patterns, it ultimately underscores the unique complexities of today’s warming. The rapid pace of change, coupled with anthropogenic influences, establishes our current climate situation as distinctly perilous. Thus, with history as our guide, we must emerge with resolve, leveraging our understanding and capacity to advocate for sustainable practices. The past offers lessons, but the choices we make today will define future generations. The stakes are higher than ever, and the need for decisive action is paramount.

To address the severity of the situation, collaboration at local, national, and global levels is essential. With knowledge as our ally, we can seek solutions that honor historical wisdom while also innovating to forge a sustainable path forward. The time to act is now, as the legacy of our response to the current climate crisis will inevitably shape the narrative of humanity’s relationship with the environment for centuries to come.