Concrete has long been heralded as one of the most ubiquitous building materials in contemporary construction, lauded for its durability, versatility, and structural integrity. However, beneath its hard surface lies a staggering environmental impact that contributes significantly to global warming. This examination delves into the multifaceted climate cost of concrete, encompassing its production processes, operational usage, and subsequent waste management, effectively illuminating its role in exacerbating climate change.

The genesis of concrete begins with its primary component: cement. The production of cement is notoriously carbon-intensive, accounting for approximately 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions. The process requires the calcination of limestone (calcium carbonate) at extreme temperatures, typically above 1,400 degrees Celsius. This not only releases carbon dioxide as a byproduct but also necessitates the burning of fossil fuels, further contributing to greenhouse gas emissions. The scale of cement production has been escalating, driven by rapid urbanization and infrastructure demands in emerging economies. This increase signifies an expanding planetary footprint, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable alternatives.

Moreover, the global appetite for concrete extends beyond mere structures; it has seeped into every echelon of modern life. From residential homes to monumental skyscrapers, roadways, and bridges, concrete’s omnipresence is palpable. The implications of this reliance are profound. As cities burgeon, so too does the demand for concrete, leading to the extraction of vast quantities of raw materials, such as sand and gravel. This has incited ecological degradation in riverbeds and coastal regions, disrupting local ecosystems and biodiversity.

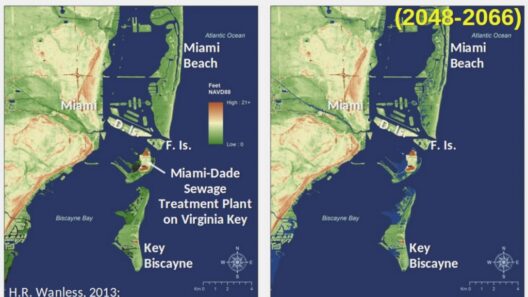

In addition to the initial carbon footprint associated with its production, the operational phase of concrete structures also contributes to climate change. The thermal mass of concrete buildings can result in higher energy consumption for heating and cooling. While concrete possesses favorable thermal properties, it can also exacerbate the urban heat island effect, which refers to the phenomenon where urban regions experience significantly higher temperatures than their rural counterparts. As urban areas expand, this effect becomes increasingly pronounced, leading to heightened energy demands and increased emissions from cooling systems.

Furthermore, the end-of-life considerations for concrete are frequently overlooked. The typical lifespan of concrete structures can exceed several decades, yet their eventual demolition presents an additional set of environmental challenges. Concrete waste is one of the largest components of landfill waste; when disposed of improperly, it contributes to soil contamination and adversely affects water quality. Additionally, recycling initiatives have been hampered by a lack of infrastructure and the technical challenges of reusing concrete. Although recycling concrete can divert waste from landfills and reduce the reliance on virgin materials, the transformed product often lacks the performance characteristics required for high-quality applications.

To mitigate the climate cost of concrete, innovative solutions are emerging. Researchers and engineers are exploring supplementary cementitious materials, such as fly ash, slag, and silica fume, which can replace a portion of cement in concrete mixes. These materials not only reduce the carbon footprint of concrete but also enhance its mechanical properties. The implementation of alternative binders, such as geopolymers, presents another promising avenue. These materials, derived from industrial byproducts, can potentially lower carbon emissions during production while providing comparable performance to traditional cement.

Moreover, the concept of carbon capture and storage (CCS) is gaining traction within the cement industry. By capturing carbon dioxide emitted during the cement production process, it can be sequestered underground or utilized in other applications, thereby reducing its contribution to climate change. While CCS is still in its nascent stages, its potential to transform the landscape of cement manufacturing cannot be understated.

Additionally, the architectural and engineering communities are increasingly prioritizing the use of low-carbon materials and green certifications, such as LEED and BREEAM, to promote sustainable building practices. Investment in research and development of alternative materials is key to catalyzing a shift away from traditional concrete usage. Moreover, fostering a circular economy, wherein materials are reused and recycled, presents an opportunity to significantly reduce the environmental impact of concrete.

Ultimately, addressing the climate cost of concrete requires a multi-faceted approach encompassing innovation, policy changes, and public awareness. Policymakers must recognize the substantial emissions associated with cement production and implement regulations that incentivize sustainable practices and technologies within the industry. Furthermore, public engagement and education are critical in fostering a collective commitment to addressing the environmental ramifications of construction practices. The responsibility lies not solely with manufacturers but also with consumers, architects, and urban planners who play vital roles in shaping our built environment.

In conclusion, concrete’s climate cost represents a critical intersection of innovation, environmental responsibility, and societal needs. As the world confronts the daunting realities of climate change, the imperative to re-evaluate our material choices has never been more pressing. Concrete, with its formidable legacy, offers both challenges and opportunities. To navigate this intricate terrain, concerted efforts towards sustainable practices, alternative materials, and circular economies must be at the forefront of future developments, ensuring that progress does not come at the cost of our planet.