In recent discussions about climate change and its implications for society, a provocative phrase attributed to former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher has resurfaced: did she actually refer to global warming as a “marvelous excuse”? This question sparks interest, considering Thatcher’s role as a pioneering leader in addressing environmental issues during her tenure in the 1980s. However, the context surrounding her comments provides a broader spectrum of interpretation that merits exploration.

To adequately address this query, we must delve into the historical context of Thatcher’s leadership. In the wake of the industrial revolution, the late 20th century witnessed a mounting awareness of environmental degradation. Scientific evidence began linking industrial activities to climate change, prompting global leaders to reconsider their approaches to governance and environmental policy. Thatcher, a scientist by training, was notably influenced by this emerging narrative.

Thatcher is often lauded for her early recognition of the risks posed by climate change. In a landmark speech given in 1988 to the Royal Society, she articulated the dangers of global warming, employing scientific evidence to underscore her points. Here, she emphasized the necessity for international cooperation and the urgency of implementing policies that would curb greenhouse gas emissions. In this context, her message was decidedly serious, aligning with the growing consensus among scientists about the threat of climate change.

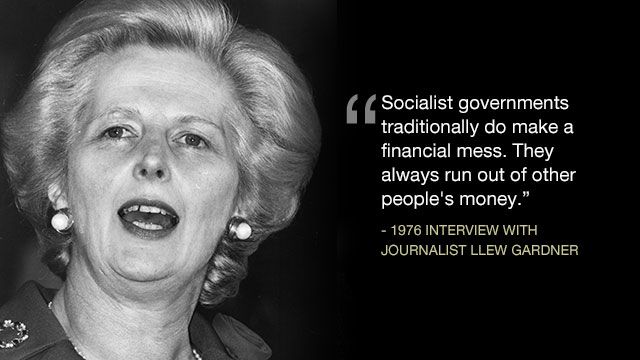

However, the idea that she considered global warming a “marvelous excuse” raises critical questions about intent and interpretation. This phrase, if taken at face value, suggests a dismissive attitude toward the climate crisis, as if it were merely a convenient pretext for political maneuvering or economic restructuring. Yet, what did she mean by this assertion? The challenge lies in deciphering her intentions while also considering the broader socio-political climate of the time.

A nuanced examination reveals that Thatcher’s comments were often a critique of the political mismanagement and inefficiencies she perceived within the environmental movement. By characterizing global warming as potentially a “marvelous excuse,” she may have been highlighting the tendencies of some politicians to exploit environmental issues for short-term gains rather than addressing the substantive, systemic changes required to effect meaningful progress. This interpretation invites a deeper dialogue about the motivations behind political discourse surrounding climate change.

Furthermore, one must consider the role that economic models played during her administration. Thatcher’s government championed neoliberal policies, advocating for deregulation, privatization, and reduced state intervention. In this milieu, environmental concerns sometimes took a backseat to economic development and growth. Thus, her rhetoric could be seen as not just a commentary on climate change, but as a critique of how environmental issues were utilized to justify potential regulatory overreach.

Interestingly, Thatcher’s juxtaposition of economic and environmental interests encapsulates a persistent dilemma in climate discourse today. This raises a playful yet poignant question: does emphasizing the urgency of climate action risk being perceived as a “marvelous excuse” to impose scrutiny on individuals and organizations? As it stands, there exists a fine line between genuine advocacy for sustainability and an opportunistic approach to policy-making. It is essential to navigate this treacherous terrain with diligence and discernment.

The ramifications of Thatcher’s legacy in environmental politics remain profound and far-reaching. The term “marvelous excuse,” regardless of its original intent, encapsulates ongoing tensions in modern climate activism. The battle to prioritize environmental sustainability over corporate interests continues to be a point of contention in numerous political arenas. As climate activists grapple with the severity of climate change, they must confront the reality that calls for action may be weaponized for political gain.

The notion of global warming as an “excuse” also invites scrutiny of the broader societal attitudes toward environmental stewardship. In an era characterized by climate apathy and denialism, it calls into question the degree to which people and governments are willing to act responsibly. Are we, as a global community, using climate change as a scapegoat for inaction, or are we genuinely committed to addressing the crisis? This inquiry challenges us to reflect on our priorities and obligations to future generations.

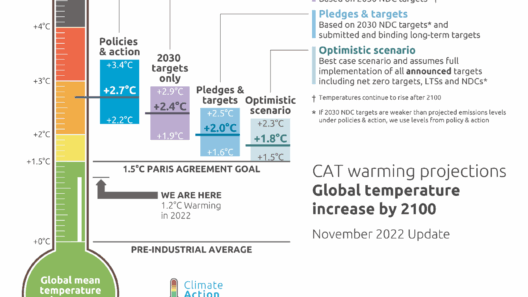

As we dissect the implications of the phrase attributed to Thatcher, it is crucial to acknowledge the evolving nature of our relationship with the environment. The dialogue surrounding climate change has matured significantly since the 1980s, yet contentious debates about the path forward persist. Energy policies, technological innovations, and international collaboration are serviceable tools in mitigating climate risks, but they require robust political will and public support.

In conclusion, Margaret Thatcher’s retrospective comment regarding global warming as a “marvelous excuse” serves as a launching point for broader reflections on the intersection of politics and environmentalism. It challenges activists and policymakers alike to reassess the motivations and frameworks through which climate discourse is conducted. Essential to this discourse is the recognition that confronting climate change is not merely about addressing technical issues but also about fostering a culture of accountability and transparency. As global temperatures rise and clock ticks, embracing a holistic and sincere approach to climate leadership may ultimately determine our collective fate.