The intersection of war and environmental science is a multifaceted domain that often eludes thorough scrutiny. The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II serve as poignant case studies in this regard. Would it be a leap of faith to posit that these cataclysmic events altered Earth’s climate? The exploration of such ramifications not only unveils historical truths but also facilitates contemporary dialogues about the intersections of conflict, human activity, and ecological outcomes. This inquiry delves into the hypothesis that the WWII bombings may have induced climatic changes, evaluating immediate and long-term implications on Earth’s atmosphere.

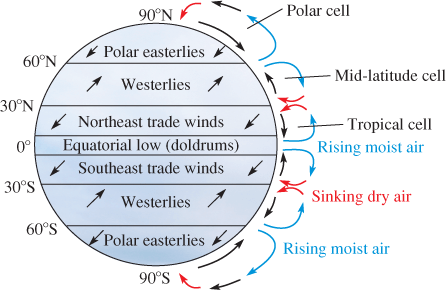

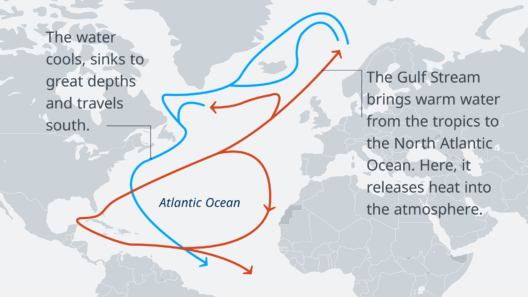

Firstly, it is imperative to understand the sheer magnitude of the bombings. The atomic explosions obliterated entire cities, releasing vast amounts of energy and incinerating everything in their vicinity. Beyond the immediate loss of life and infrastructure, these detonations unleashed a wealth of particulate matter and gases—such as smoke and soot—into the atmosphere. The proliferation of aerosols disrupts solar radiation, leading to what is termed ‘radiative forcing.’ This phenomenon is critical in understanding how large-scale atmospheric alterations can potentially lead to significant climatic shifts.

After WWII, the world witnessed the onset of the “Nuclear Winter” theory, which posited that extensive nuclear warfare could result in catastrophic climatic consequences. While the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings may not have sparked a global cooling event akin to what was theorized—given their localized nature—the concept warrants consideration. Researchers suggested that the soot from nuclear explosions could envelop the Earth, leading to a decrease in surface temperatures. Drawing a parallel with volcanic eruptions, which release significant particles that obscure sunlight, the analogy is compelling. The immediate aftermath of such bombings could theoretically sow the seeds for temporary climatic anomalies.

Moreover, the effects of the bombings extend into the realm of radiological fallout, which can alter not only biodiversity but also human ecosystems over time. The dispersal of radioactive materials created a legacy of contamination that lingers to this day. Fallout may not directly correlate with climate change; however, it does have long-term environmental ramifications that could exacerbate climate variability. For instance, biomes contaminated by radioactive isotopes may experience shifts in flora and fauna, thereby influencing carbon sinks and, subsequently, global carbon cycles. The intricate web of ecological interactions becomes pivotal in understanding how localized devastations could appear as broader geological phenomena.

In examining any climatic shifts provoked by the bombings, we must also consider the era’s agricultural practices. The disruptions in food systems due to bombings—both in Japan and countries involved in the war—threw agrarian societies into turmoil. Alterations to crop yields in the aftermath of such destruction could have had rippling effects on local climates, primarily through land-use change. Deforestation for immediate farming needs, alongside urban sprawl in post-war reconstruction, exacerbated the thermal dynamics of cities and the rural-urban climate interfaces. Transitioning from natural ecosystems to engineered landscapes alters albedo—how much sunlight the Earth’s surface reflects—which can influence localized heating, contributing to urban heat islands.

On a broader scale, the culmination of WWII saw the rise of denser urban populations within rebuilt cities, aspiring to economic resurgence. This demographic transition harbored its challenges. The increased emissions from industrial resurgences accelerated the anthropogenic impact on climate change during the latter half of the 20th century. Such emissions, compounded with pre-existing pollution and environmental degradation, pushed atmospheric carbon dioxide levels to unprecedented heights. As cities burgeoned, heat-related mortality surged, and the impact of climate change became more palpable. In this context, the WWII bombings do serve as a harbinger, illuminating how war can engender cascading effects on global climate systems.

Furthermore, the psychological and cultural legacy of the bombings contributes to shifting paradigms in environmental consciousness. As countries like Japan grappled with the memories of war and devastation, their post-war policies increasingly embraced anti-nuclear sentiments and environmental reforms. This shift offers an indirect commentary on how sociopolitical landscapes can affect climate action. A populace scarred but resilient may turn towards sustainability, approaching ecological issues with scrutinizing eyes that appreciate the fragility of life. Such an evolution in collective consciousness may pivot around narratives established through the darkest periods of human history.

In summary, while direct causative links between the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and climate change may not manifest as linear or easily discernible, they prompt valuable discourse regarding humanity’s broader impact on climatic systems. Engaging with the historical hypothesis of WWII as a catalyst for environmental shifts unravels complexities and underscores the necessity for rigorous analyses of how conflicts intertwine with climate. Moving forward, the exploration of these historical contexts is vital, promoting a deeper understanding of war’s legacy on both human and non-human systems. Without such clarity, society risks repeating past mistakes in increasingly paradoxical futures defined by both warfare and environmental calamity.