Have you ever wondered how the forces that act on objects can influence their energy? Specifically, when discussing mechanical energy, one might pose the question: Do non-conservative forces decrease mechanical energy? To answer this intriguing inquiry, we must first unravel the nuances of mechanical energy and the classification of forces.

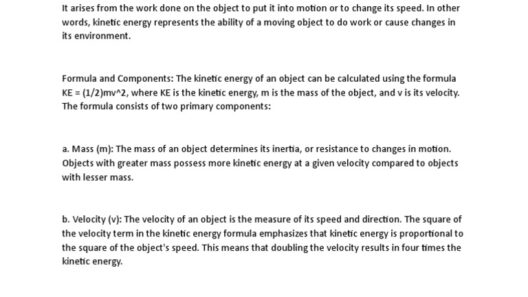

Mechanical energy is a form of energy that is associated with the motion and position of an object. It is typically divided into two categories: kinetic energy, which pertains to an object in motion, and potential energy, which is the stored energy based on an object’s position relative to a reference point. For instance, a rock perched at the edge of a cliff possesses gravitational potential energy due to its elevation. When released, this energy transforms into kinetic energy as the rock plunges downward.

In the realm of classical mechanics, forces can be categorized as conservative or non-conservative. Conservative forces, such as gravitational and elastic forces, are intriguing because the work done against them is path-independent. The energy spent in lifting an object is restored when the object is lowered, making these forces efficient in energy conservation. In contrast, non-conservative forces—friction, air resistance, and tension in inelastic materials—have a different modus operandi. They often convert mechanical energy into other forms—most commonly thermal energy—through processes like heat generation.

Let’s delve deeper into non-conservative forces. Friction is perhaps the most ubiquitous non-conservative force encountered in daily life. When you slide a book across a table, friction opposes the motion, acting as a detriment to the overall mechanical energy of the system. The kinetic energy that once propelled the book forward is gradually dissipated as thermal energy, warming the surface of the table and the book itself.

Consider the implications of this transformation on mechanical energy. When a non-conservative force like friction acts upon an object, it effectively strips away kinetic energy that could have been harnessed for motion. The result is a net decrease in mechanical energy. So, when posed with the question of whether non-conservative forces decrease mechanical energy, the answer is yes—without a doubt. But it is important to understand the mechanisms at play.

To illustrate the dynamics of non-conservative forces, envision a roller coaster. As the ride ascends, potential energy is maximized at the apex of the track. However, as it zooms downhill, the thrill is accompanied by the action of non-conservative forces like air resistance and friction with the tracks. While energy is conserved in an ideal world devoid of these forces, real-life conditions lead to a departure from this theoretical scenario. The kinetic energy witnessed as speed peaks is not twice that potential energy due to the aforementioned forces diminishing the total mechanical energy.

Furthermore, this conversion of mechanical energy into heat due to non-conservative forces poses a significant concern in industrial applications. For instance, when machines run, they encounter numerous non-conservative forces, leading to energy loss through friction. As a result, engineers often design systems with the ability to manage or mitigate these energy losses. Improved lubrication techniques, for example, aim to reduce friction, thereby conserving mechanical energy.

However, the challenge extends beyond machinery into broader conversations about energy efficiency across various sectors. In modern society, the emphasis on energy conservation is more pronounced than ever—with rising concerns over climate change and fossil fuel dependency. Thus, understanding the role of non-conservative forces in energy degradation can illuminate pathways toward innovative solutions. Can we redesign transportation systems to minimize friction? What about leveraging renewable energy technologies that inherently reduce reliance on mechanical systems plagued by non-conservative forces?

Moreover, non-conservative forces play essential roles in ecological systems. For instance, consider the embankments of rivers. The continuous erosion of soil, influenced by gravitational forces (a conservative force) coupled with sediment movement aided by water currents (non-conservative), reveals a fundamental interaction between energy forms. The challenge is to examine how this energy loss in natural landscapes can inform our environmental stewardship. By understanding these concepts, we can devise strategies for sustainable land management that curtail erosive forces.

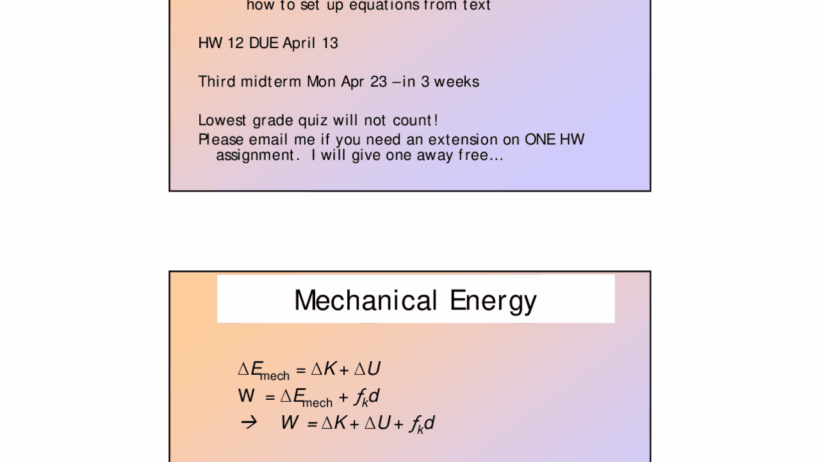

To navigate back to the central question, do non-conservative forces decrease mechanical energy? The evidence strongly positions itself in favor of this assertion. Vital relationships between kinetic energy and non-conservative work illustrate how mechanical energy dissipates in the presence of friction and air resistance. Understanding this energy exchange can propel advancements in technology and environmental practices alike. As we ponder the perpetual nuances of energy dynamics, it beckons us to consider the broader implications of energy transformation that extend far beyond the classroom.

In conclusion, the interplay between non-conservative forces and mechanical energy offers intriguing insights. From enhancing organizational efficiency in machinery to catering to the sustainability movement in environmental contexts, the implications are profound. The challenge now lies in harnessing this understanding to innovate and progress toward a more energy-efficient future, ensuring less waste of the precious energy reserves that sustain our planet.