The relationship between volcanic eruptions and global temperature shifts is both intricate and multifaceted. At first glance, one might ponder an intriguing question: do volcanic eruptions primarily exacerbate global warming, or are they more likely to induce temporary cooling? To delve into this conundrum, it is essential to dissect the mechanics of volcanic activity and its implications on Earth’s climate.

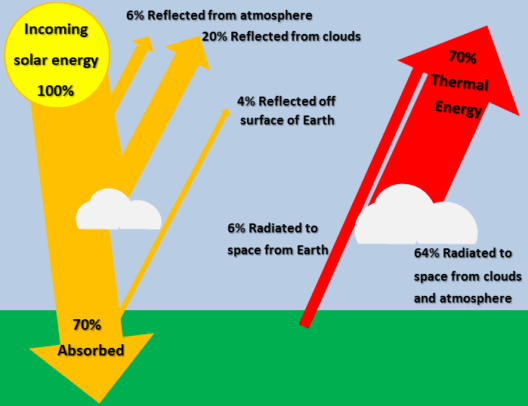

Volcanic eruptions release an array of gases and particulate matter into the atmosphere, with the most significant contributors being carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2). While carbon dioxide is a well-known greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere, sulfur dioxide behaves differently. Upon release, SO2 can react with water vapor to form sulfuric acid aerosols, which reflect solar radiation back into space. This prompts the question: can the cooling effects of these aerosols counterbalance the warming effects of CO2?

Historically, the temperature effects of eruptions have varied significantly based on their size, duration, and intensity. For instance, the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 stands as a prime example of a significant volcanic event that yielded noticeable cooling effects. The eruption injected vast amounts of SO2 into the stratosphere, leading to a global temperature drop of approximately 0.5 degrees Celsius in the years following the event. Yet, a single large eruption does not convey the full picture. This poses an intriguing challenge: should we consider the potential for both short-term cooling and long-term warming when evaluating volcanic activity?

To further understand this duality, we must consider the frequency and scope of volcanic eruptions. The Earth experiences thousands of eruptions annually, yet only a handful are classified as large enough to have substantial climatic effects. Smaller eruptions tend to contribute to localized weather patterns without significant global ramifications. Therefore, while the cooling effect of a major eruption can be pronounced, its temporal limitations leave much to be desired in the broader context of anthropogenic climate change.

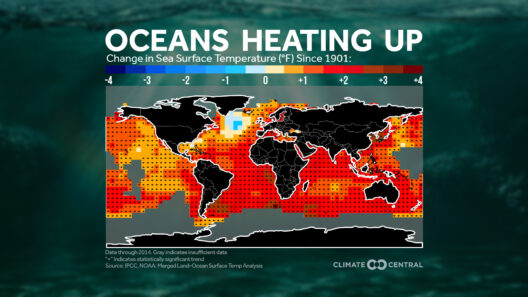

The crux of the issue lies in distinguishing between natural climate variations and anthropogenic influences. Human activities, particularly the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation, have led to a substantial increase in atmospheric CO2 levels. The contrast between this long-term warming trend and the transient cooling effects of volcanic eruptions underlines a fundamental challenge: are we adequately addressing the root causes of climate change, or are we merely responding to a series of symptoms?

Furthermore, it is paramount to recognize the potential compounding effects of volcanic eruptions with other climatic phenomena. The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), for example, is another critical variable influencing global temperatures. When intertwined with volcanic eruptions, these events can create complex interactions that further obscure the overall climate impacts. With the potential for combined warming and cooling effects, the global community faces the daunting task of disentangling these influences.

Another area of consideration is the geological context of eruptions. Stratovolcanoes and shield volcanoes emit gases and materials differently, which can lead to variable climatic outcomes. For instance, explosive stratovolcanoes tend to produce more ash and sulfur aerosols, while effusive shield volcanoes are more prone to releasing CO2. Understanding these differences adds layers to the interpretation of volcanic contributions to climate dynamics.

Moreover, assessing the long-term impacts of volcanic gases requires scrutinizing their residence time in the atmosphere. While SO2 aerosols may remain in the stratosphere for a few years, CO2 persists for decades to centuries. This differential persistence emphasizes the prevailing concern regarding the long-term ramifications of anthropogenic activities versus the episodic nature of volcanic eruptions.

It is also essential to consider the ecological consequences of volcanic eruptions in relation to climate change. The ash fallout can severely disrupt local ecosystems, affecting flora and fauna, and altering land use. These ecological shifts can feed back into the climate system, complicating existing processes. Therefore, while a singular eruption may momentarily cool the globe, the aftermath may engender long-term ecological shifts that have further implications for climate resilience and adaptation.

As we navigate this multifaceted challenge, it becomes increasingly apparent that the query surrounding volcanic eruptions—whether they serve as agents of global warming or cooling—has no definitive answer. The interplay of chemical, physical, and biological processes complicates our understanding. Furthermore, the pendulum swings towards a need for robust climate action grounded in the knowledge that the primary driver of contemporary climate change lies within human activity.

In conclusion, addressing the climate crisis necessitates a holistic approach that factors in both natural and anthropogenic influences. While volcanic eruptions can undoubtedly influence short-term climate fluctuations, they cannot be viewed in isolation from the broader context of human-induced climate change. Acknowledging the complexities inherent in these interactions is essential in crafting effective strategies to combat the pressing issue of global warming. As we continue to unravel these scientific intricacies, we must strive for informed action that mitigates the impacts of human activity on our planet’s delicate climate system.