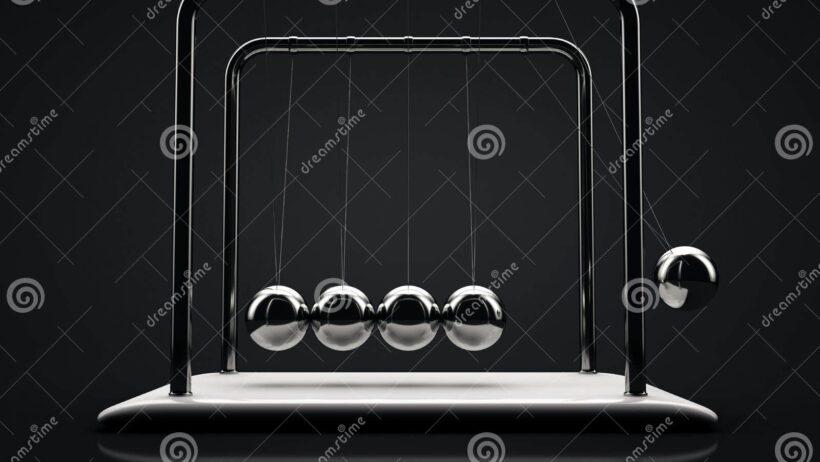

The pendulum, a simple yet profound mechanical device, has captivated the minds of physicists and philosophers alike for centuries. At its core, the pendulum serves as a remarkable demonstration of the laws of physics, particularly the Law of Conservation of Energy. This principle asserts that energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only transform from one form to another. To understand if a pendulum proves this law, one must delve into its operational dynamics, explore various types, and consider real-world implications.

Initially, let’s grasp the basic mechanics of a pendulum. A classic pendulum consists of a weight, or bob, suspended from a fixed point by a string or rod. When displaced from its resting position and released, the pendulum swings back and forth. This action embodies a continuous interplay between potential energy and kinetic energy. At the highest point of its swing, the pendulum possesses maximum potential energy due to its elevated position. Conversely, at the lowest point, where the pendulum is at its fastest, kinetic energy peaks.

An essential understanding lies in the conversion of these energy types. As the pendulum swings downwards, potential energy converts into kinetic energy. Conversely, as it ascends, kinetic energy transforms back into potential energy. This cyclical transition epitomizes the Law of Conservation of Energy, as the total mechanical energy remains constant in the absence of external forces like air resistance or friction. Importantly, this remains true regardless of the height from which the pendulum is released, as long as the system is closed.

Furthermore, analyzing different types of pendulums can deepen our understanding of energy conservation. The simple pendulum is the most common form, usually referencing a weight at the end of a string. However, variations such as the compound pendulum, which consists of a rigid body capable of swinging about a fulcrum, reveal additional complexities in energy conservation. Moreover, the concept of a physical pendulum introduces rotational dynamics, challenging us to consider not just translational kinetic energy but also rotational kinetic energy.

From a mathematical perspective, the analysis of pendulums involves intricate equations. A simple pendulum’s period— the time it takes to complete one full oscillation— can be approximated with the formula (T = 2pisqrt{frac{L}{g}}), where (T) is the period, (L) is the length of the pendulum, and (g) is the acceleration due to gravity. This relationship illustrates the pendulum’s dependence on its length rather than mass, suggesting energy’s reliance on specific parameters of the system design.

The conservation of energy principle is not merely a theoretical abstraction; it has practical ramifications across various domains. In engineering, pendulums inspire designs in clocks, seismographs, and even amusement park rides. Understanding the conservation of energy in these systems may lead to enhanced efficiency and functionality. For example, the precise movement of a pendulum provides invaluable insights into timekeeping mechanisms, ensuring accurate chronometry through minimized energy loss.

Moreover, the pendulum’s simplicity serves as an educational tool in teaching foundational physics concepts. Students and observers alike can visualize energy transformations in a tangible manner. This approach not only fosters a deeper comprehension of energy conservation but also inspires curiosity about broader principles of physics and motion.

However, one must acknowledge limitations in observing the pendulum’s energy conservation in real-world applications. Friction and air resistance inevitably lead to energy dissipation, introducing external forces that disrupt the idealized model. Over time, the pendulum will lose amplitude, gradually coming to rest. This phenomenon underscores the importance of understanding that while the pure Law of Conservation of Energy holds in an idealized state, real-world applications necessitate consideration of dissipative forces and their impact on energy states.

Interestingly, the pendulum also provides a valuable lens through which to examine various physical phenomena, such as chaos theory. In systems involving multiple interdependent pendulums, slight variations in initial conditions can lead to vastly different outcomes. This behavior exemplifies how energy conservation relates to complex systems, showing us that while energy may be conserved, the trajectory of that energy can yield unpredictable results.

In conclusion, the pendulum distinctly demonstrates the Law of Conservation of Energy through its mechanical movements. By illustrating the interplay of potential and kinetic energy forms, it serves as a microcosm of broader physical laws. Different pendulum types offer nuanced perspectives on energy transition, while real-world applications highlight potential energy losses and system complexities. Ultimately, the pendulum stands as an enduring symbol of the principles of physics, emphasizing the importance of energy conservation in both theoretical and practical realms. As we continue to explore these principles, it remains critical to appreciate the broader implications for technological advancements and educational endeavors in an age increasingly concerned with resource sustainability.