In the complex chiaroscuro of climate change, the use of biomass as a fuel source often stands at the intersection of hope and undeniable environmental impact. This duality is particularly evident when examining wood pellets as an energy source. As we peel back the layers of this issue, we may find that biomass, particularly wood pellets, can be both a lifeline and a noose in our struggle against global warming.

Wood pellets, derived from compacted sawdust and other wood waste materials, have emerged as a popular substitute for fossil fuels in the quest for renewable energy. Advocates hail wood pellets as a sustainable alternative, claiming that they can help transition society away from carbon-intensive fuels. However, the burning of wood pellets raises critical questions about their actual contribution to climate change. To unravel this dilemma, one must consider how biomass interacts with the broader environmental landscape.

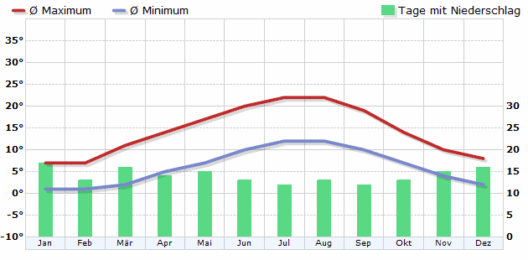

The fundamental argument for biomass lies in its presumption of carbon neutrality. When wood is harvested and burned, it releases carbon dioxide (CO2) back into the atmosphere. However, proponents argue that new trees will eventually grow to absorb this CO2, thus creating a cyclical carbon loop: cutting down trees, burning them, and replanting a new generation of trees. At first glance, this phenomenon appears to be a closed, carbon-neutral cycle. In reality, this simplistic portrayal belies the intricacies involved in the growth and decay processes of forests.

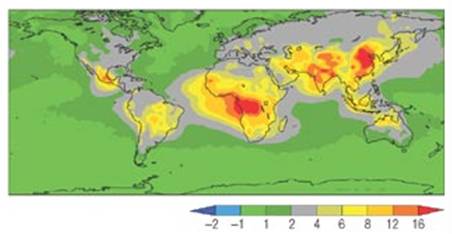

Consider the metaphor of a forest as a living bank. Trees are not merely carbon stores; they are ecosystems, habitats, and carbon sequestration systems. When we “withdraw” trees in the form of biomass for wood pellet production, we deplete not just the carbon stock but also the habitat integrity and biodiversity that exists within that ecosystem. It takes many years, often decades, for new trees to mature. In the meantime, the emissions released from the combustion of wood pellets contribute to the atmospheric carbon concentrations that drive global warming.

The destruction of forests—even when followed by replanting—fundamentally alters the intricate balance of ecosystems. Additionally, the age of the trees that are harvested plays a critical role. Older trees, often harvested for wood pellets, sequester carbon at a far higher rate than younger trees. Therefore, cutting down mature forests disrupts this natural high-efficiency carbon capture and leads to a net increase in atmospheric carbon levels.

Moreover, the implications extend beyond carbon dioxide emissions. The combustion process of wood pellets also releases other greenhouse gases, such as methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), which have much more significant global warming potentials than CO2. While the carbon emitted may seem to be quickly accounted for, the multifaceted nature of emission profiles reveals the extensive environmental ramifications of burning wood pellets.

A pivotal aspect to consider is the sustainability of sourcing the wood used for pellets. Many pellet manufacturers obtain their materials from unsustainable logging practices, where forests are depleted faster than they can regrow. This unsustainable harvesting not only exacerbates climate issues but also leads to the loss of biodiversity, increased soil erosion, and water cycle disruption, creating a ripple effect that undermines the very ecosystems we rely upon for a balanced environment.

In the context of global energy needs, we must ponder whether the allure of biomass is worth the ecological costs incurred. While reliance on wood pellets may offer a temporary reprieve from fossil fuel dependency, enabling a smoother transition in energy production, it simultaneously complicates the narrative surrounding the urgent need to reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions. The quest for alternatives should not blindly allow emissions to persist in different forms; we must seek genuine solutions.

This is not to dismiss biomass entirely—when managed prudently, responsibly, and sustainably, biomass can contribute positively to renewable energy portfolios. Instead, it calls for a more discerning examination of practices and systems surrounding pellet production and usage. Emphasizing sustainable forest management practices, enhancing carbon capture techniques, and developing policies that prioritize biodiversity alongside energy production are essential strides toward reconciling wood pellet use with environmental stewardship.

As we navigate the crossroads of energy and climate equity, clear distinctions must be drawn between ‘clean’ and ‘green.’ The term “clean energy” can be misleading if it allows for practices that ultimately perpetuate pollution. In essence, the discourse surrounding wood pellets is not a simple binary. It reveals a tapestry woven of conflicting interests, a narrative fraught with consequences that must be articulated with clarity.

In conclusion, the question of whether burning wood pellets contributes to global warming is not merely a matter of combustion; it encompasses broader ecological, social, and economic implications. The path forward requires an intricate dance of ambitions, responsibilities, and wisdom. It beckons the call for proactive measures that prioritize sustainability and true climate action. As environmental stewards, it becomes imperative to differentiate between options that merely represent ‘lesser evils’ and those that embody authentic sustainability. In this intricate web, understanding, not just adhering to convenient narratives, may well be our most formidable ally in combating climate change.