Energy conservation principles serve as the bedrock of classical physics, yet they often prompt intriguing questions and scenarios. One such question might be: does friction matter in the principle of energy conservation? It seems simple, perhaps even playful at first glance, but delving deeper reveals the intricate dance between energy forms under the influence of this everyday force.

To understand the relationship between friction and energy conservation, we must first define our terms. Energy conservation, in its most rudimentary form, states that energy cannot be created or destroyed but can change forms. For instance, potential energy may transform into kinetic energy, and vice versa. However, when friction comes into play, the entire scenario alters, prompting us to reassess our understanding of this fundamental principle.

Friction is the resistive force that occurs when two surfaces move against one another. It is an omnipresent phenomenon, governing everything from the motion of vehicles on roads to the simple act of walking. While friction can impede motion, it also plays a significant role in various energy transformations. Herein lies the challenge: does friction merely dissipate energy as heat, or does it play a more nuanced role in energy conservation?

In typical contexts, friction is seen as a detriment to efficiency. For example, in mechanical systems, friction tends to reduce the overall energy output, as some energy converts into heat. This reduction in energy efficiency raises concerns in engineering and environmental realms, where maximizing energy output is crucial. However, it is vital to note that this heat generation resulting from friction doesn’t signify a loss of total energy; rather, it represents a transformation into a different form—thermal energy.

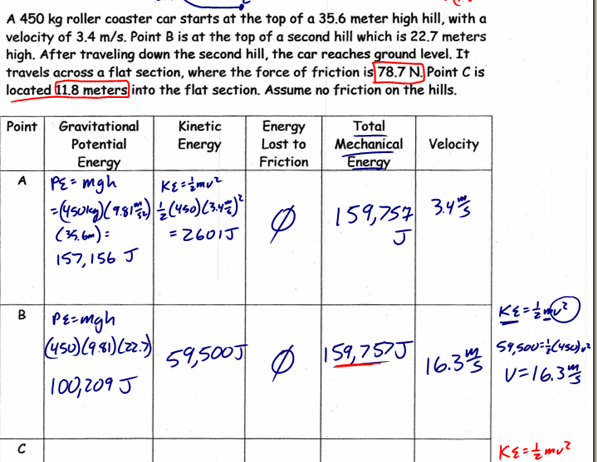

The concept of energy conservation remains sound, but one must consider the substances and conditions at play. When discussing friction in energy conservation, we can distinguish between two key scenarios: mechanical friction in engines and kinetic friction in daily activities. Mechanical friction is particularly germane when discussing machines, where energy transformations dictate efficiency and performance levels.

In a friction-laden system, the apparent loss of mechanical energy could lead to a misinterpretation of the conservation law. When a car engine operates, the work done on the pistons converts fuel’s chemical energy into kinetic energy for the car’s movement, while heat dissipates due to internal friction and the contact between moving components. This heat disperses into the environment, yet it does not signify that energy has been lost; instead, it highlights energy’s transformative capacity.

Moreover, kinetic friction also has implications beyond mere energy dissipation. It contributes to traction, which is critical for vehicles to accelerate, decelerate, and navigate safely through various terrains. Without friction, energy conservation would become abstract in practical terms, as machines and systems would struggle to function effectively. Thus, friction can be viewed not solely as a hurdle but as an essential facilitator of energy transfer and mechanical operation.

As we extend our inquiry, it becomes essential to consider the broader implications of friction’s role in energy systems. In natural systems, friction influences energy conservation in processes such as erosion, sediment transport, and atmospheric dynamics. For instance, water flowing over rocks in a river experiences friction that dissipates energy, affecting the water’s speed and behavior downstream. The ecological impacts of this energy transformation can be profound, shaping habitats and influencing biodiversity.

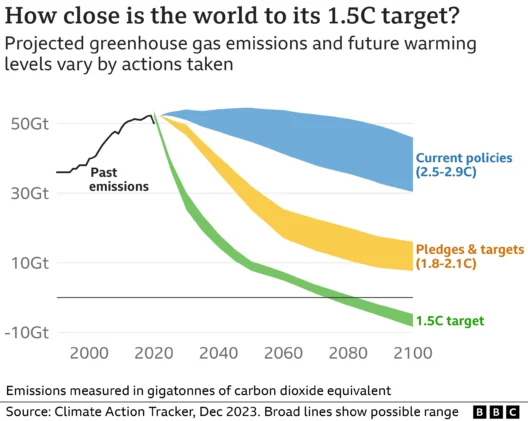

Furthermore, the ramifications of friction reach into the realm of climate change. In the context of energy generation and consumption, frictional forces can lead to inefficiencies in renewable energy technologies. Turbines, solar panels, and transportation systems all face the challenge of friction, which can lead to a cumulative increase in energy demand, thereby affecting fossil fuel consumption and carbon emissions. Understanding and mitigating the effects of friction can result in improved efficiencies, offering pathways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

A critical question arises: can we harness friction to our advantage in the pursuit of sustainable energy practices? Research into triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs)—devices that convert mechanical energy from friction into electrical energy—provides promising insights. These devices can potentially generate energy from everyday activities, such as walking or moving machinery. This innovation exemplifies how friction, often viewed merely as a resistive force, can be repurposed as a source of energy in our quest for sustainability.

In conclusion, while friction undeniably transforms energy and can lead to dissipative losses, it also plays a complex, multifaceted role in the broader context of energy conservation. Rather than viewing friction strictly as an adversary, it invites us to explore innovative solutions and find ways to engineer systems that minimize its negative impacts while capitalizing on its benefits. Moving forward, scientists and engineers must embrace this challenge, continually evolving our understanding of energy conservation in a world characterized by interdependent forces. Ultimately, the interplay between friction and energy conservation not only shapes our physical systems but also propels us toward a more sustainable and conscious future.