Global warming, the gradual increase in the Earth’s average surface temperature due to human activities, is a discussion that invariably conjures vivid imagery of melting glaciers and sweltering summers. But amidst these mental images, a thought-provoking question emerges: does global warming refer to the entire planet, or are we merely observing localized phenomena? To unravel this conundrum, it is essential to delve into the complexities of climate systems and recognize the interplay between global and regional climatic changes.

First, it is pertinent to establish what global warming signifies. At its core, global warming is a long-term rise in Earth’s temperature, primarily attributed to greenhouse gas emissions produced by industrialization, deforestation, and other human-induced activities. This rise is documented globally, yet its manifestations can vary significantly across different regions. Herein lies the challenge: while global warming is a systemic, planet-wide phenomenon, its effects are not uniformly experienced.

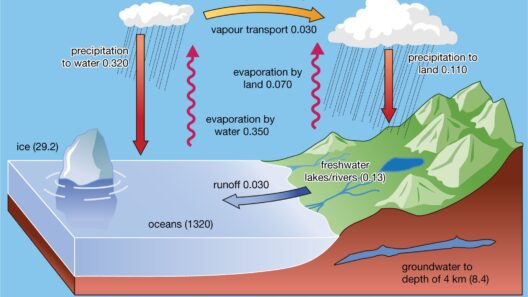

To understand this divergence, it is essential to explore the concept of climate variability. The Earth’s atmosphere is a complex system influenced by numerous factors, including geographical location, ocean currents, and atmospheric conditions. These variables collectively contribute to a variety of climate zones, each with distinct characteristics. For instance, regions near the poles experience different warming trends compared to those near the equator. This leads to an important distinction: warming is indeed a global issue, but its consequences can be sporadic and unpredictable based on local conditions.

One striking example of this disparity is the Arctic region, which is warming at a rate approximately twice that of the global average. The phenomenon known as Arctic amplification occurs when the loss of sea ice leads to a decrease in the reflective surface area of the planet. Consequently, more solar energy is absorbed, leading to accelerated warming. In contrast, some temperate regions may experience minimal temperature increases. This highlights the paradox of global warming—while the planet’s average temperature is on the rise, some areas may remain relatively unaffected.

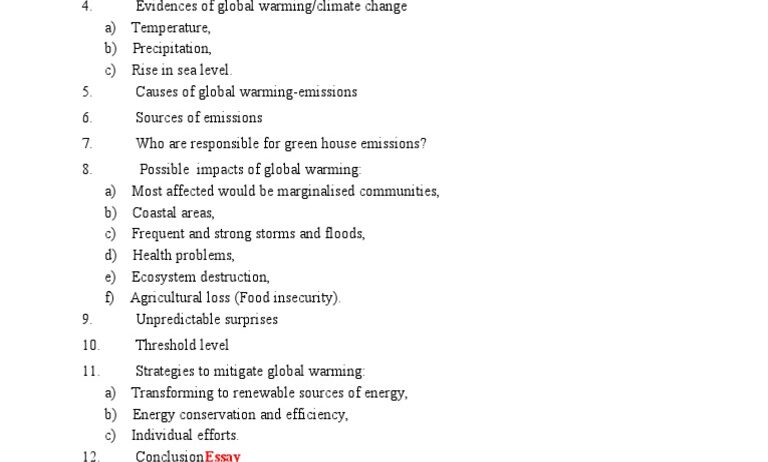

Moreover, regional climate patterns can also result in something termed “climate feedback loops.” For example, increased atmospheric temperatures can lead to altered precipitation patterns, further influencing local ecosystems. Areas that traditionally thrive on consistent weather patterns may face severe droughts or floods as a direct result of shifting climate dynamics. This phenomenon underscores how global warming, while a universal crisis, has significant regional implications that vary widely based on local ecological, economic, and social factors.

Let us consider, for instance, the plight of coastal communities. As sea levels rise due to thermal expansion and melting ice sheets, specific regions are increasingly vulnerable to inundation. For these coastal areas, the impacts of global warming are acutely felt—eroding shorelines, saline intrusion into freshwater supplies, and heightened storm surges are but a few examples of the localized challenges. Here, global warming serves as a specter, casting shadows over daily life, while it may not provoke the same urgency in landlocked or high-altitude regions.

With this understanding, a crucial question arises: how can we reconcile the global nature of warming with the localized effects observed across continents? This is imperative, especially in the context of policy-making and climate action. Global initiatives, such as the Paris Agreement, aim to foster international cooperation to limit temperature increases; however, the efficacy of such agreements hinges on recognizing regional disparities and vulnerabilities. A one-size-fits-all approach risks overlooking the unique circumstances of specific locales.

Furthermore, the socio-economic contexts of different regions exacerbate the impacts of global warming. Developing nations often possess limited resources to adapt to changing climatic conditions, making them more susceptible to the adverse effects. In contrast, wealthier nations, while also impacted, typically have the means to invest in mitigation and adaptation strategies. This discrepancy elucidates an ethical dimension to the discussion: global warming, while a shared predicament, is experienced unevenly, with marginalized communities bearing the brunt of its consequences.

One cannot dismiss the psychological aspects of this discourse either. For many, the term “global warming” evokes thoughts of a distant crisis, disconnected from everyday life. This perception becomes a barrier to fostering a collective sense of urgency. If individuals believe that global warming is a far-off reality, they may feel less compelled to act. Conversely, when showcased through the lens of local experiences—wildfires, flooding, or unseasonably warm winters—the narrative shifts, galvanizing communities to engage in climate action.

As critical as addressing the inequities of climate change is understanding the interconnectedness of our global system. Natural events, such as El Niño and La Niña, demonstrate how climate variations in one part of the world can catalyze fluctuations in another. Therefore, while global warming is indeed a planetary issue, the repercussions ripple through every corner of the globe, blurring the lines between global phenomena and localized impacts.

In conclusion, while global warming symbolizes a pervasive threat that transcends geographical boundaries, its repercussions are felt unevenly across different regions. This multifaceted reality demands that we approach climate policy with an awareness of regional contexts and a commitment to equity. By doing so, we can strive towards a more informed, unified, and actionable response to one of the most pressing challenges of our time. Addressing global warming requires not only acknowledging the science but also understanding the diverse human experiences intertwined within its narrative.