In recent years, the discourse surrounding climate change has evolved, moving beyond mere acknowledgment of the issue towards an examination of the contributors to this global crisis. Among the myriad factors implicated in climate change, the consumption of meat has emerged as a focal point of intense scrutiny. This discussion raises a pivotal question: Is eating meat a recipe for global warming? The answer lies in understanding the intricate interplay between our dietary choices and the environment.

To grasp the impact of meat consumption on climate change, one must first appreciate the agricultural processes that underpin meat production. Animal agriculture is resource-intensive; it demands vast expanses of land, copious amounts of water, and significant energy inputs. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has noted that livestock production accounts for approximately 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This statistic is staggering when we consider the enormity of the contribution compared to other sectors.

One of the primary ways in which meat production exacerbates global warming is through the emission of methane, a potent greenhouse gas. Methane is produced during the digestion of food by ruminant animals, such as cows and sheep, through a process known as enteric fermentation. This gas is significantly more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide, posing a severe threat to climate stability. Methane’s short atmospheric lifespan—approximately a decade—means that curtailing emissions could provide relatively rapid benefits in mitigating climate change. However, the scale at which meat production continues to grow complicates these efforts.

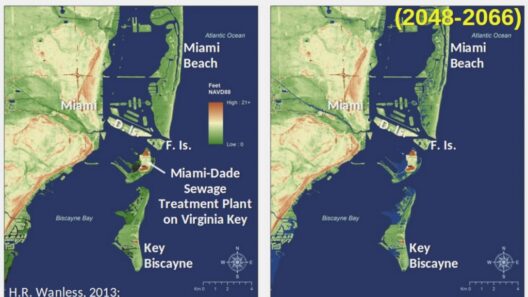

Furthermore, the land required for raising livestock has resulted in widespread deforestation. Forest ecosystems act as crucial carbon sinks, absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The clearing of forests to create pasture for cattle and cropland for animal feed releases stored carbon back into the atmosphere, further contributing to the greenhouse effect. The Amazon rainforest, often referred to as the “lungs of the Earth,” has experienced significant deforestation primarily due to beef production. The loss of biodiversity associated with these practices further undermines ecosystem resilience, exacerbating the impacts of climate change.

Water usage is another critical aspect often overlooked in discussions about meat consumption and global warming. Livestock farming accounts for more than 70% of global freshwater use. The process of producing just one kilogram of beef requires an astounding amount of water—approximately 15,000 liters. This figure encompasses the water needed for the animals’ drinking supply, the water used in feed crop irrigation, and the water consumed during processing. As freshwater sources become increasingly scarce, the sustainability of meat production raises alarm bells for both environmental advocates and future generations.

The intersection of meat consumption and global warming extends beyond the direct environmental impacts. It also includes the socioeconomic dimensions inherent in livestock farming. Many rural communities depend on animal agriculture as a primary source of income. Thus, any discussion about reducing meat consumption necessitates the development of equitable alternatives that support these communities without exacerbating climate change. Transitioning away from intensive livestock farming towards more sustainable agricultural practices can provide dual benefits: reducing emissions and supporting local farmers.

As the dialogue evolves, so too must our perceptions of a sustainable diet. Greater awareness of the environmental implications of meat consumption has led to an increasing interest in plant-based diets. While transitioning to vegetarian or vegan lifestyles may not be feasible for everyone, reducing meat consumption—even modestly—can have a considerable impact. Initiatives advocating for “Meatless Mondays” or incorporating more plant-based meals into our daily diets are steps that individuals can undertake, contributing to a collective reduction in demand for meat.

Moreover, the food industry is beginning to respond to these shifts in consumer preference. Innovations in lab-grown meats and plant-based protein alternatives present promising solutions that can satisfy dietary preferences without imposing the hefty environmental costs of traditional meat production. These advancements signal a broader cultural shift; as consumers demand sustainable options, industries are increasingly compelled to adapt. This transition could reshape the landscape of meat consumption, driving demand for practices that prioritize ecological stability over mere profit margins.

It is imperative to recognize the interconnectedness of personal choices and global systems. The power of consumer demand is not to be underestimated; each meal represents an opportunity to influence the future of our planet. Whether through reducing consumption, exploring alternative protein sources, or supporting sustainable agricultural practices, individual actions contribute to a larger momentum of change.

In conclusion, the question of whether eating meat constitutes a recipe for global warming contemplates more than just dietary preferences; it challenges us to reconsider our relationship with food, the environment, and our role within the intricate web of life. By making informed choices and fostering a more sustainable food system, one can play a part in combating climate change. The time for action is now, and the path towards a more sustainable future begins on our plates.