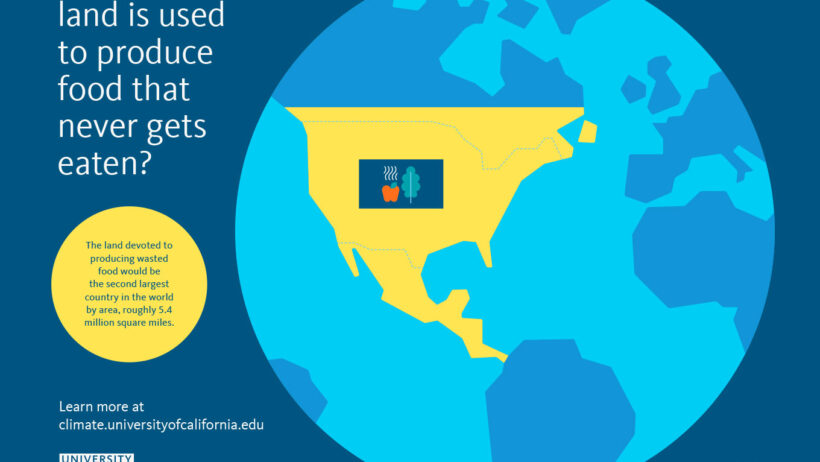

Food waste is an omnipresent concern, manifesting in households, restaurants, and institutional settings alike. Globally, approximately one-third of all food produced for human consumption is rendered inedible, translating to around 1.3 billion tons annually. But beyond the undeniable ethical implications of such waste—where individuals go hungry while vast quantities of viable food are discarded—lies an insidious connection between food waste and climate change, one that often eludes our immediate perception.

At first glance, the notion of food waste might seem primarily a matter of human negligence. Yet, when examined through a more profound lens, it becomes clear that this phenomenon is intricately tied to agricultural practices, supply chain inefficiencies, and consumer behaviors that all contribute significantly to carbon emissions. The environmental ramifications of food waste extend far beyond the simple act of throwing away leftovers; it underscores a wider systemic issue within our food production and consumption frameworks.

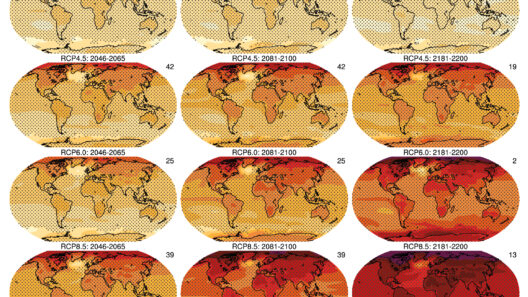

One of the most alarming aspects of food waste is its contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. When food waste decomposes in landfills, it generates substantial quantities of methane, a potent greenhouse gas with a warming potential many times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. In fact, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that food waste contributes approximately 8-10% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This stark statistic raises a critical question: How does food, a source of nourishment, turn into such a significant contributor to climate change?

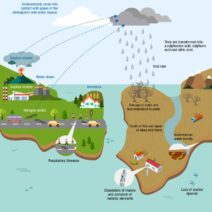

To understand this, we must delve into the lifecycle of food. Every item on our plate begins its journey in a field, requiring resources such as water, fertilizers, and energy for cultivation. Additionally, food transportation adds another layer of carbon emissions, as products are shipped across vast distances to reach consumers. Even prior to reaching our kitchens, the embodied carbon footprint of food can be substantial. When examining processed foods, the footprint becomes even more pronounced; the energy needed for processing, packaging, and storage compounds the emissions linked to the consumption of food.

Moreover, agricultural practices themselves may further exacerbate the problem. Monocropping, the practice of growing a single crop over a large area, can lead to soil degradation, which diminishes the land’s ability to sequester carbon. The use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides can also release nitrous oxide, another potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. Thus, the strategies employed to maximize yield and supply often come at an environmental cost that is directly tied to the food we waste.

In examining the consumer’s role in this conundrum, it is imperative to consider the societal attitudes toward food. The pursuit of perfection in food presentation—exemplified by the inclination to discard “ugly” fruits and vegetables—illustrates a cultural obsession with aesthetics over practicality. Supermarkets, aiming to meet consumer demands for flawless produce, often reject items that do not meet visual standards, resulting in significant surpluses that go unpurchased. Consequently, these practices not only perpetuate waste but also highlight the disconnect between consumption habits and the ecological impacts of food production.

Addressing the multifaceted nature of food waste requires a shift in perspective. Recognition of the intricate web linking our plates to the environment is vital. By understanding that our food choices have far-reaching consequences, consumers can begin to adopt more sustainable practices. Educating oneself about local food systems, choosing to buy imperfect produce, and planning meals can significantly curtail individual waste.

Businesses and policymakers also play a crucial role. Initiatives aimed at reducing food waste, such as surplus food donation programs, can repurpose products that would otherwise be discarded. Additionally, instituting government policies that incentivize reduced food waste at all levels—from producers to consumers—can reshape norms surrounding food consumption. This holistic approach dovetails with larger conversations about sustainability, heralding a collective effort that encompasses various stakeholders in the food system.

At its core, the challenge of food waste is not solely a matter of personal responsibility but a call to action for reformed practices across the food supply chain. Embracing innovative delivery and storage solutions that extend the shelf-life of food can mitigate waste at multiple junctures. Furthermore, exploring zero-waste cooking methods encourages creativity in utilizing leftover ingredients, transforming what was once regarded as waste into culinary opportunities.

In conclusion, the relationship between food waste and climate change is complex and multifaceted, encompassing agricultural practices, consumer behaviors, and systemic inefficiencies. The hidden carbon costs associated with food loss extend far beyond mere leftovers on our plates, serving as a stark reminder of the intricate connections binding our food systems to the environment. As stewards of this planet, it is incumbent upon all of us—individuals, businesses, and governments—to address the overarching issues of food waste. Through collective action, we have the power to forge a sustainable future that not only honors the resources that sustain us but also mitigates the destructive forces of climate change.