Fossil fuels have long been the cornerstone of modern civilization, powering everything from our homes to our industries. Yet, as we navigate the increasingly perilous waters of climate change, we must ask ourselves a crucial question: Are fossil fuels still the biggest offender in the climate crisis? This inquiry is not just a matter of semantics; it is pivotal for determining our path forward in mitigating the impacts of a changing climate.

For decades, fossil fuels—coal, oil, and natural gas—have been vilified as principal culprits in the accumulation of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere. The data is compelling. Emissions from burning these fuels contribute significantly to global warming, triggering a cascade of events that threaten ecological balance and human livelihoods. In fact, just in recent years, carbon emissions reached unprecedented heights, largely propelled by the relentless consumption of fossil fuels.

But can we blame fossil fuels in isolation? A closer examination reveals that the reality is far more nuanced. While fossil fuels indisputably contribute to climate change, our dependence on them is intricately woven into the fabric of societal development. Consider this: could it be that our systemic reliance on fossil fuel infrastructures, rather than the fuels themselves, is the more substantial adversary in our fight against climate change?

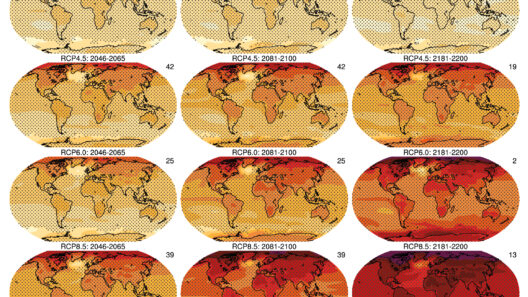

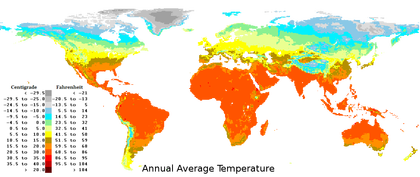

Over the past century, fossil fuels have facilitated unprecedented economic growth. The industrial revolution, which marked a turning point in human history, was powered by coal and later oil. They provided the energy needed to fabricate steel, manufacture goods, and transport materials, resulting in a standard of living that many now take for granted. However, these advancements have come at a steep price. The consequences of our fossil fuel consumption are glaring—a warmer planet, erratic weather patterns, and heightened natural disasters. Are we thus entangled in a paradox where the very engines of our progress are also engines of destruction?

The climate crisis embodies a complex interplay of natural phenomena and human enterprise. The accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere creates a feedback loop that exacerbates climate impacts, including sea-level rise and biodiversity loss. Each year, the continued reliance on fossil fuels fuels this cycle. Yet, it prompts a philosophical inquiry: to what extent are we willing to relinquish our comfort for the sake of future generations? Is it moral to sustain our lifestyle at the expense of the planet’s health?

The arguments for transitioning away from fossil fuels are diverse and multifaceted. Many proponents advocate for renewable energy sources—solar, wind, and hydropower—as viable alternatives. The technological advancements in these fields have rendered them increasingly accessible and efficient, allowing for cleaner energy production. Furthermore, the decline in the price of renewable energy sources mirrors the rising costs associated with fossil fuel extraction and environmental remediation. Transitioning to renewable energy is not merely an environmental imperative; it is also an economic opportunity.

Yet, there are challenges. The fossil fuel industry is formidable, enshrined within global economies and exerting considerable political influence. Transitioning requires substantial investments and infrastructural overhauls that many governments are hesitant to implement. The question arises: can society outpace the inertia of vested interests and the economic structures that rely on fossil fuels? This tension reveals the crux of the contemporary challenge: reforming our energy systems without triggering economic collapse.

Moreover, the allure of fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, complicates the transition narrative. Natural gas is often lauded as a “cleaner” alternative due to its lower carbon emissions compared to coal. Yet, the methane emissions associated with gas extraction and transport present an insidious threat to its sustainability as a transitional fuel. Are we, then, simply exchanging one set of problems for another? This underscores the necessity for a holistic and strategic approach to energy consumption rather than the piecemeal solutions that have predominated thus far.

In the face of these complexities, public sentiment plays an indispensable role. Educating consumers about the consequences of their energy choices and fostering an ethos of sustainability can catalyze grassroots movements that demand change. This kind of radical transformation depends substantially on collective action; it is the responsibility of society to scrutinize and challenge fossil fuel consumption patterns. Additionally, individuals must grapple with their roles in perpetuating fossil fuel reliance. Are we perpetuating the status quo by favoring convenience over sustainability?

Indeed, the climate crisis illuminates a stark reality: fossil fuels are not the sole offenders, but they are certainly among the most significant. Their environmental ramifications create an undeniable impetus to reevaluate our energy policies and consumption habits. While fossil fuels have powered our past, they cannot dictate our future. The transition to a sustainable energy regime offers the chance to redefine human progress in an environmentally harmonious manner.

As we grapple with these challenges, we find that the path forward is rife with uncertainty yet replete with potential. To escape the grip of fossil fuels, society must embrace innovation, challenge existing paradigms, and cultivate an unwavering commitment to the planet’s health. The question remains: will we seize this opportunity, or will we continue to drift along the currents of convenience that lead us ever closer to climate catastrophe? It is a question that deserves fervent consideration amidst the urgent call for action.