As the world grapples with the existential threat of climate change, an often overlooked yet significant contributor to global warming emerges from unexpected places: the fields where livestock graze. Understanding the intricate relationship between agriculture—particularly livestock farming—and climate change can reshape our priorities and perspective. It’s not merely about the carbon footprint of our vehicles; the very food on our plates plays a pivotal role in atmospheric changes.

The nexus between agriculture and climate change is a multifaceted issue. Livestock farming is a chief perpetrator, releasing various greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere, with methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) being the most egregious. These gases have a much stronger warming potential than carbon dioxide (CO2). To put it succinctly, while CO2 persists for centuries, both methane and nitrous oxide significantly contribute to the immediate warming of the Earth.

Methane, generated predominantly from the digestive processes of ruminants such as cattle, is particularly alarming. Cattle and sheep utilize a unique digestive mechanism involving microbes in their stomachs that breaks down food—this process, known as enteric fermentation, releases methane as a byproduct. In fact, livestock accounts for approximately 14.5% of global GHG emissions, a statistic that conveys the urgency of addressing agricultural practices directly contributing to climate change.

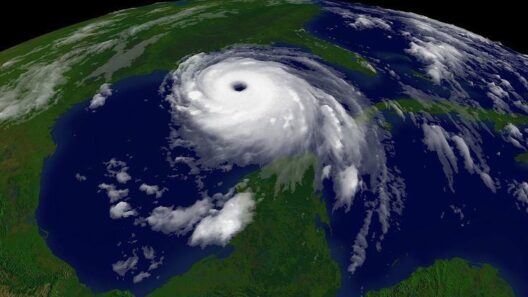

The scenario becomes even more sobering with the consideration of feed production. The cultivation of feed crops such as corn and soy not only requires vast quantities of fossil fuels for machinery but also necessitates the use of fertilizers that lead to nitrous oxide emissions. Drastically, the emissions attributable to the production and transportation of feed must be accounted for when assessing the overall climate impact of livestock farming. Furthermore, the land use changes due to converting forests and grasslands into arable lands eliminate natural carbon sinks, exacerbating the situation.

But livestock farming does not operate in isolation. It is inextricably tied to water pollution, deforestation, and biodiversity loss. Monoculture agriculture often accompanies livestock operations, reducing soil health and increasing erosion. Water resources are also at risk; meet production requires significant quantities of water for both the animals themselves and the irrigation of feed crops. This increasing water demand threatens the sustainability of freshwater resources, particularly in arid regions.

The role of deforestation cannot be underestimated. In regions like the Amazon rainforest, vast tracts of forest are cleared to create pasture for cattle, leading to the release of stored carbon into the atmosphere. This is not merely an environmental concern; it threatens the diverse ecosystems that depend on these forests, as well as the Indigenous communities whose livelihoods are intertwined with the land. The cyclical nature of these issues illustrates the depth of the environmental crisis fostered by livestock farming.

In addition to the practices on the ground, the socio-economic aspects of livestock farming also play a substantial role in its climate impact. The rising global demand for meat, driven by population growth and changing dietary preferences, fuels industrial farming practices that prioritize efficiency over sustainability. The economic model that supports these practices often sidelines local, sustainable farming methods that could mitigate climate impacts. Shifting this demand to more sustainable agricultural practices presents a challenge but also an opportunity.

Regenerative agriculture emerges as a possible solution. This farming approach focuses on restoring soil health, improving biodiversity, and sequestering carbon. Regenerative practices work toward rebuilding the natural resilience of ecosystems rather than depleting them. Techniques such as rotational grazing, where livestock are moved frequently to allow pastures to recover, can enhance soil carbon storage. By creating a symbiotic relationship between livestock and the land, it is possible to reduce methane emissions while improving the ecological balance.

Furthermore, shifting diets offers profound potential to address the ramifications of livestock farming. Plant-based diets generally require fewer resources, reduce GHG emissions, and support sustainable land use practices. Advocates of reducing meat consumption encourage utilitarian approaches that emphasize health benefits alongside environmental impact. The intersection of personal choice with environmental stewardship illustrates how individual actions can contribute to broader systemic changes.

Yet, transitioning towards sustainable agriculture and dietary shifts is fraught with challenges, including cultural factors, economic implications, and political resistance. Governments and industries must collaborate to incentivize agricultural practices that minimize environmental impacts. Policies that advocate for carbon credits, subsidies for regenerative farming, or financial support for ecosystem preservation could steer the agricultural sector towards a more sustainable future.

In conclusion, the journey from fields to fever is not simply about livestock’s contribution to global warming; it encompasses a broader dialogue surrounding sustainability, ecological integrity, and global food security. Recognizing the implications of livestock farming on climate change invites new perspectives on our agricultural systems, while urging us to reconsider the relationship between our food choices and the health of our planet. Investment in sustainable practices, alongside a collective shift in dietary habits, is imperative to curbing the momentum of climate change and protecting the Earth for future generations. As climate activists and advocates, our challenge is to illuminate these connections and galvanize action in the face of this pressing global crisis.