As the planet grapples with the multifaceted conundrums of climate change, the prospect of manipulating the Earth’s climatic systems through geoengineering emerges as both a tantalizing potential remedy and a labyrinthine ethical quandary. This concept is akin to wielding a double-edged sword; it carries the promise of safeguarding ecosystems but also harbors inherent risks that could exacerbate the very crises it seeks to alleviate. In this discourse, we shall navigate the convoluted waters of geoengineering, weighing its double-edged nature and the implications for our environmental future.

First, let us delineate what geoengineering entails. At its core, geoengineering refers to a suite of deliberate techniques aimed at intervening in the Earth’s climate system to mitigate the detrimental effects of global warming. These methods broadly fall into two categories: carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and solar radiation management (SRM). CDR focuses on extracting greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, while SRM seeks to reflect a small proportion of the sun’s energy back into space, thereby counteracting the heating effects of climate change. Each approach carries distinctive attributes, benefits, and perils that must be meticulously examined.

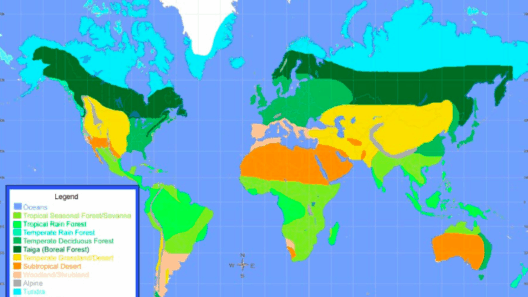

Carbon dioxide removal stands as a hopeful beacon in the fight against climate change. Techniques such as afforestation, ocean fertilization, and direct air capture are prime examples. The metaphor of a sponge is fitting here; these methods function similarly by soaking up carbon dioxide, striving to reduce the concentration of this greenhouse gas in the atmosphere. However, such sponges are not without their drawbacks. For instance, afforestation can alter local ecosystems, potentially leading to unintended consequences that could compromise biodiversity. Additionally, the vast scale required for effective carbon removal poses logistical challenges and questions about land use and competition with food production.

Similarly perplexing is the realm of solar radiation management. Techniques such as stratospheric aerosol injection—where reflective particles are dispersed into the atmosphere—are evocative of a sun shade, aiming to shield the Earth from the ferocious glare of the sun. This approach might seem straightforward, yet it invites a deluge of uncertainties. The deployment of aerosols could disrupt precipitation patterns, precipitating droughts in some regions while inundating others with excessive rainfall. This planet is a complex interwoven tapestry; tugging one thread can unravel numerous others.

As with any bold endeavor, the ethical ramifications of geoengineering are indubitably significant. The notion of ‘playing God’ often looms large in discussions surrounding these interventions. Should humanity assume the role of climate architect, invariably entangled in a permanent game of trial and error? This apprehension produces a hesitance, a reticence rooted in the fear of unintended consequences that could lead to a scenario far worse than our current predicaments. Additionally, the potential for moral hazard must not be overlooked. The allure of geoengineering could assuage the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, fostering a complacent attitude that relinquishes accountability in favor of technological fixes.

Furthermore, the governance and regulation of geoengineering projects present another intricate challenge. The global nature of climate change necessitates collaborative efforts across borders. However, the disparate political, economic, and cultural contexts of various nations complicate consensus-building. Who should wield the authority to initiate geoengineering projects, and what mechanisms should be in place to ensure transparency and equitable distribution of benefits and burdens? In this regard, the ‘tragedy of the commons’ emerges as a pressing concern: an unregulated geoengineering initiative could lead to a scenario where the interests of a few supersede the welfare of the many.

In striving for a middle ground, it is crucial to embrace a multifaceted approach to climate change that acknowledges both the potential of geoengineering and its limitations. Innovation in clean energy, conservation, sustainable agriculture, and emission reduction must remain at the forefront of our collective efforts. Geoengineering should be viewed not as a solitary panacea but as one potential tool in a diverse arsenal aimed at fostering environmental resilience. Rather than relying heavily on one particular strategy, we must embrace a holistic approach that integrates various methodologies, safeguarding against the pitfalls of any single solution.

In conclusion, the discourse surrounding geoengineering embodies both the spirit of audacious innovation and the sobering weight of responsibility. It serves as a clarion call for meticulous examination of our advancements in technology and their implications for the planet. As we delve into uncharted territories in the quest for climate solutions, a prudent balance must be struck between ambition and caution. The stakes are undeniably high. Our actions today reverberate across generations, shaping the landscape of not only our environment but our very existence. Therefore, it is imperative to engage in these conversations, to analyze and critique, as we chart a sustainable future for generations to come.