Has the United States truly felt the insidious embrace of global warming since the 1970s? This seemingly innocuous question serves as a doorway to explore an intricate web of environmental, social, and economic consequences that have unfolded over the past several decades. On the surface, the answer appears to lean towards an unyielding affirmative; however, a closer examination reveals a myriad of complexities and nuances that merit further discussion.

In the late 20th century, a pronounced shift in climatic patterns began to emerge, signaling the onset of changes that would reverberate throughout various ecosystems. Rising temperatures, particularly notable since the 1970s, have engendered a cascade of effects across American landscapes. According to NOAA, the average temperature in the contiguous United States has increased by 1.5°F since 1970. This seemingly modest rise belies a surging undercurrent of phenomena that are anything but benign.

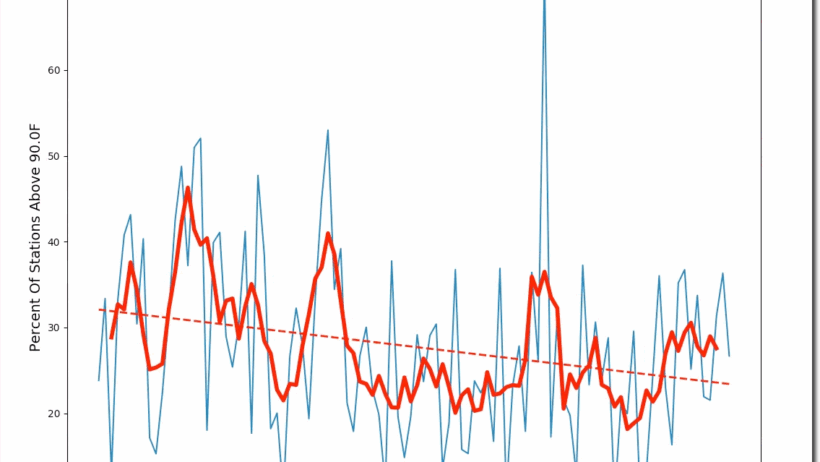

Consider the heat waves that have become increasingly commonplace. Cities such as Phoenix and Las Vegas have been grappling with record-breaking temperatures, with their annual counts of 100-degree days spiraling upwards. The challenge here lies not merely in dealing with discomfort but in confronting the impact on public health. Prolonged exposure to extreme heat exacerbates pre-existing medical conditions and is disproportionately harmful to vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and low-income communities.

Another critical manifestation of global warming is the alteration in precipitation patterns. The Midwest has seen a doubling of heavy rainfall events, leading to increased flooding incidents. For agricultural sectors, which form the backbone of the American economy, these changes pose significant risks. Crop yields are often threatened by unpredictable weather, with farmers at the mercy of torrential downpours that erode soil and wash away nutrients. Coupled with an increased prevalence of droughts in the West, the agricultural industry faces a precarious balancing act of managing not only production but also sustainability.

Coastal regions are not exempt from the repercussions of climate change. Since the 1970s, sea levels along the U.S. coasts have risen by nearly 8 inches, a stark reminder of the realities of climate change. This rise has triggered a multifaceted existential crisis. Communities in Florida, New Jersey, and Louisiana are grappling with the encroachment of seawater that threatens homes, infrastructure, and livelihoods. The concept of “managed retreat”—the idea of relocating whole communities—has emerged as a contemplative, albeit contentious, solution. Still, the logistical, emotional, and financial complexities it entails loom large.

Moreover, the proliferation of extreme weather events is increasingly evident. Hurricanes have intensified, observed through the lens of both increasing wind speeds and rising sea temperatures, which exacerbate their destructive potential. The Atlantic hurricane season, especially after the 1970s, has been punctuated by a surge in notably powerful storms, wreaking havoc on coastal societies and burdening government disaster response systems. This trend raises numerous questions: How do communities rebuild? At what cost do we value resilience?

In addition to natural disasters and their aftermaths, wildfires have become another harbinger of climate change, particularly in the western United States. States like California have endured increasingly severe fire seasons, with fires spreading more rapidly due to hotter temperatures and prolonged droughts. The implications extend beyond immediate property loss—air quality deteriorates, public health suffers, and ecosystems face irreversible damage. The results can incite a tension between conservation efforts and the need for economic development as state resources become stretched thin.

Beyond the physical and economic ramifications, global warming has also infused a sense of urgency into the realm of policy-making and public consciousness. Advocacy for sustainable practices, the transition to renewable energy sources, and initiatives aimed at carbon footprint reduction have gained momentum. The 1970s marked a pivotal period in environmental consciousness, yet the urgency has since escalated. The challenge now lies in galvanizing collective political will to effectuate meaningful change. Will the U.S. embrace this challenge head-on, or will inertia reign?

Public opinion has shifted significantly over the decades; climate change is no longer a distant or abstract concern for many. Surveys reveal that more Americans are recognizing climate change as an immediate threat. This marks a turning point—one where grassroots movements and youth activism are pressing for accountability and action. Yet, encumbered by geopolitical complexities and differing ideologies, the road to cohesive action remains fraught.

In conclusion, has the U.S. felt the impact of global warming since the 1970s? The evidence, both qualitative and quantitative, paints a picture of climate change deeply interwoven into the fabric of American life. From the parching deserts of the Southwest to the flood-ravaged streets of the Midwest, the implications are vast and multifaceted. As we navigate this maze of challenges, the real question remains: Are we prepared to confront the magnitude of this crisis with the urgency it demands? The answers may lie within the collective will to enact change, hold accountability, and foster resilient societies prepared to adapt amidst a warming world.