In the ongoing discourse surrounding climate change, an unsettling question has emerged: Have scientists inflated climate data? This inquiry encapsulates a nexus of skepticism, scientific integrity, and the urgency of environmental advocacy. To comprehend the nuances of this issue, it is imperative to dissect the various dimensions at play, including the nature of climate data, the methodologies employed in its collection, the motivations that drive scientific research, and the implications of misinterpretation.

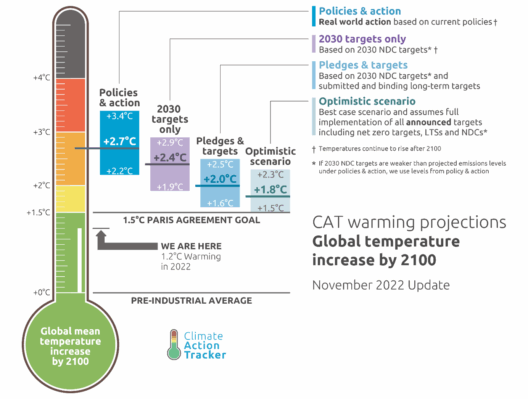

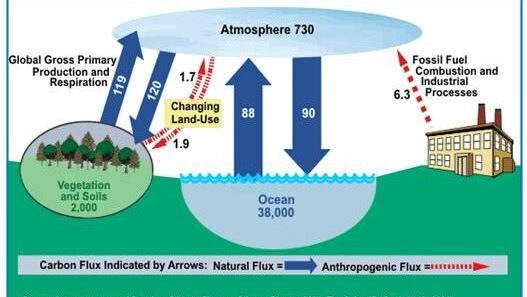

Firstly, understanding the types of climate data is essential for grasping the potential for inflation. Climate data largely falls into two categories: observational data and modeled projections. Observational data is derived from instruments measuring temperature, atmospheric gases, and ecological changes, while modeled projections are generated using climate models that simulate future conditions based on various scenarios, including greenhouse gas emissions. These models, though robust, rely on assumptions that could lead to divergent outcomes when new data emerges.

Data collection methods are paramount in ensuring accuracy. Satellite observations, ground-based measurements, and ocean buoys are typical tools for gathering atmospheric and oceanographic data. Each method has limitations, such as spatial coverage, resolution, and temporal frequency. Consequently, scientists often adjust or normalize data to account for these limitations. This brings forth the concern of potential bias; adjustments can sometimes be perceived as an inflationary tactic rather than a methodological necessity. Transparency in these adjustments is crucial to maintaining public trust.

Furthermore, the motivations behind climate research are diverse. Scientists may pursue studies to enhance public awareness, influence policy decisions, or simply contribute to scientific knowledge. However, fears of funding biases can emerge. Research institutions, non-profits, and governmental bodies often sponsor climate studies. If funding sources are perceived as having a vested interest in alarmist data, skepticism can escalate. Critics may argue that the pressure to produce compelling results leads to an inflation of data to meet expectations.

Moreover, the intricacies of data interpretation warrant scrutiny. Climate change is an inherently complex phenomenon involving multifaceted interactions among atmospheric, terrestrial, and oceanic systems. The confluence of variables often leads to simplified narratives in the media, which can inadvertently distort scientific findings. For example, an increase in global temperatures might be presented without adequate context, neglecting regional variations and the multifarious factors influencing climate dynamics. This has the potential to foster distrust in the scientific community when the public encounters discrepancies in how data is portrayed.

Disinformation campaigns further complicate the landscape surrounding climate data. Social media platforms, filled with both misinformation and extraneous opinions, serve as echo chambers for climate denial. Such campaigns frequently exploit scientific uncertainty, framing legitimate scientific debates as evidence of systemic data inflation. This diverts attention from the overwhelming consensus among climate scientists regarding anthropogenic impacts on the environment and may engender a dangerous complacency among the public.

It is essential to also consider the role of peer review in ensuring the reliability of climate data. The scientific community employs peer review as a method to validate research findings before publication. This rigorous process is designed to minimize bias and inflate concerns. Nevertheless, the system is not infallible. Instances of publication bias, where studies with significant findings are more likely to be published, can skew perceptions of scientific consensus. When negative or neutral results fail to gain traction, the public may only hear one side of the climate story, inadvertently reinforcing the notion of inflated data.

Addressing the question of data inflation requires a multifaceted approach rooted in scientific literacy and critical thinking. As an informed citizenry is key to engaging constructively with climate issues, fostering educational initiatives around climate science can mitigate misinformation. Environmental education in schools and community programs focused on data interpretation can empower individuals to discern between well-substantiated findings and hyperbolic claims.

Furthermore, enhancing transparency in climate science is vital. Open-access data repositories, where raw data and methodologies are shared, can bridge the gap between academia and the general public. This accessibility allows for independent validation of findings and cultivates a culture of accountability among scientists. Encouraging collaboration between scientists and communicators can ensure that complex data is conveyed in an understandable manner, enriching public discourse.

In conclusion, the question of whether scientists have inflated climate data is complex and multifaceted. While concerns regarding bias, funding motives, and data interpretation merit consideration, it is crucial to approach this topic through a lens of scientific integrity. The battle against climate change requires solidarity among scientists, policymakers, and the public. By fostering informed discussions and maintaining vigilance against misinformation, society can constructively navigate the intricacies of climate science and work collaboratively toward a sustainable future.