The relationship between work and the conservation of energy is a fundamental concept in the field of physics, profoundly influencing our understanding of various physical phenomena. This relationship is often encapsulated within the Work-Energy Theorem and the Law of Conservation of Energy, both of which are vital for elucidating the mechanisms underlying energy transfer and transformation. This exploration delves into the intricacies of work, energy, and their interconnections, emphasizing the significance of these principles in our daily lives and the broader context of climate change.

Work is defined as the process of energy transfer that occurs when a force acts upon an object causing it to move. Mathematically, work is expressed as the product of force (F) and displacement (d), taking into account the angle (θ) between them: W = F × d × cos(θ). This equation highlights that work is contingent on both the magnitude of the force applied and the distance over which it is exerted, as well as the direction of the force relative to motion. For instance, lifting an object against gravity requires positive work, while applying brakes to a moving vehicle constitutes negative work, effectively reducing its kinetic energy.

Energy, on the other hand, is the capacity to do work. Various forms of energy exist, including kinetic, potential, thermal, and chemical energy, each transitioning between forms during various processes. Kinetic energy (KE), the energy of motion, is described by the equation KE = 1/2 mv², where m represents mass and v velocity. Potential energy (PE), commonly gravitational in nature, is defined as PE = mgh, where g is the acceleration due to gravity and h is the height above a reference level. Recognizing these distinctions is pivotal for comprehending how energy is transformed when work is done.

The Work-Energy Theorem serves as a bridge between work and energy, positing that the total work done on an object equals the change in its kinetic energy. This principle elucidates that when work is performed on an object, it results in an alteration of the object’s energy state, specifically its kinetic energy. Consequently, when energy is added to the system via work, its kinetic energy increases, demonstrating a direct dependence between these quantities.

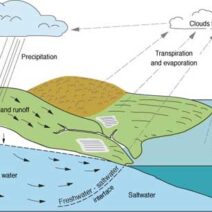

In the broader context of the conservation of energy, this principle asserts that the total energy in an isolated system remains constant; energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only transformed from one form to another. An example of this principle can be observed in roller coasters, where potential energy at the highest point converts to kinetic energy during descent. The interplay of energy types illustrates the overarching connection between work and the conservation of energy.

Moreover, understanding work and energy conservation is essential when addressing contemporary challenges such as climate change. Energy consumption and efficiency are pivotal issues as societies strive to minimize greenhouse gas emissions. In various sectors, including transportation, industry, and electricity generation, how work is performed affects energy consumption and, subsequently, the environmental impact. Transitioning to renewable energy sources and enhancing energy efficiency contributes to reducing the ecological footprint, aligning societal actions with the principles of energy conservation.

In transportation, for example, maximizing work efficiency can substantially reduce fuel consumption. Electric vehicles (EVs) harness electrical energy optimization, utilizing regenerative braking systems that convert kinetic energy back into stored electrical energy. By strategically controlling how work is done, the energy lost during braking is mitigated, showcasing a practical application of energy conservation principles.

In industrial processes, a deeper understanding of the work-energy relationship can foster innovations that minimize energy waste. Implementing technologies that maximize output while minimizing the input energy required can significantly enhance efficiency. For instance, the integration of energy-efficient machines, combined with optimized workflows, can lead to a transformative reduction in energy demands, echoing the conservation of energy ethos.

Another realm deeply intertwined with this discussion is renewable energy generation. Wind and solar power systems encapsulate work and energy conservation in their operation. Wind turbines convert kinetic energy from wind into mechanical energy, powering generators that transform this energy into electricity. Here, the relationship between work and energy is vital, as the work done by the wind signifies a tangible energy transfer that ultimately serves to meet human energy demands sustainably.

As we navigate towards a sustainable future, recognizing the synergies between work, energy, and conservation is essential. Advocating for practices that align with these principles can lead to a reduction in fossil fuel dependency and contribute to mitigating the impacts of climate change. Society must prioritize educational initiatives that fundamentally change how individuals perceive work and energy in their daily lives, ultimately fostering a culture of sustainability.

In conclusion, the intricate relationship between work and the conservation of energy is a cornerstone concept in understanding physics and its applications in various fields. This relationship is not merely theoretical; it holds weight in real-world applications, especially in the context of addressing climate change. By optimizing work processes and enhancing energy conservation, we can forge a more sustainable future and promote a healthier planet. Understanding and harnessing these principles is crucial as we face the environmental challenges of the 21st century.